Depression and anxiety both are common and often co-occur among children and adolescents. If they remain untreated, these common mental health problems can persist into adulthood, leading to adverse individual, social, and economic consequences. Thus, it is important to identify treatments that can address both conditions simultaneously in a manner which is developmentally appropriate, contextually sensitive and scalable in terms of resources required.

Behavioural activation (BA) is one such technique that fits these requirements. Previous research with adults has shown that it can be used across a range of disorders, is culturally sensitive, can be delivered by non-specialists and is a cheaper alternative to cognitive behaviour therapy. It is suitable for children and adolescents owing to its simple, behavioural, concrete focus. Given this, BA seems to hold significant promise for the treatment of children and adolescents.

BA as a technique has its origin in traditional behaviour therapy. The core mechanism of BA has been theorised at systematically increasing a person’s engagement in adaptive activities, decreasing activities that maintain withdrawn and avoidant behaviour, and problem solve barriers to increase access to reward. Techniques of activity monitoring and activity scheduling are core elements of BA. However, other elements such as contingency management, values, and goal assessment, skill training such as problem-solving, relaxation, targeting verbal behaviours, and targeting avoidance; have often been used along with these core elements.

In 2016, the COBRA trial found that behavioural activation was not inferior to CBT for adults with depression, suggesting it might be an effective alternative at least for a certain segment of the population.

Methods

In a recent article, Martin and Oliver (2019) systematically reviewed and synthesised evidence on characteristics of BA focused intervention and their effectiveness on depression and anxiety among children and adolescents. The specific objectives of their review were:

- Examine evidence for the effectiveness of BA intervention on depression and anxiety outcomes in children and adolescents.

- Describe participant characteristics, types of difficulties and intervention characteristics in studies with BA interventions.

- To identify what has been learnt about adapting BA for children and young people, particularly in relation to parental involvement.

To fulfil the above objective, the researchers systematically reviewed various databases such as PsycInfo, PubMed, EMBASE to identify published studies that evaluated BA focused intervention for children and adolescents up to age of 19 years. Both controlled and uncontrolled studies were included in the review. Studies that used BA as part of a broader cognitive-behavioural or other therapeutic approach were excluded from the review.

For each of the eligible study, the researchers extracted details of the sample characteristics (including sample size, participant ages, settings, psychological difficulties assessed), intervention characteristics (dosage, duration, intervention composition, delivery agents), study design, outcomes indicators, and information relating to the adaptation of BA for use with children and young people. Meta-analysis was conducted with data reported in randomised controlled trials (RCT).

Results

As part of their systematic review, researchers screened 9,062 articles and 19 studies met inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. The 19 relevant studies included 12 studies with case studies/case series design, three studies with uncontrolled pre-post design and four studies with RCTs design. Most of the studies originated from high-income countries. BA has been used to treat depression, anxiety, and co-morbid anxiety and depression, across these studies.

The key findings from the studies are summarised below:

- Intervention composition and dosage: BA intervention evaluated in these studies varied in complexity, with the number of intervention elements varying between 3 and 10. Activity monitoring and scheduling were used in all studies. Functional analysis and value and goal assessment were other frequently used elements in these interventions. The dosage of sessions varied greatly across interventions, with the total number of sessions ranging between 5 and 22.

- Intervention setting, modality, and providers: Most of the interventions were delivered face-to-face in an outpatient clinical setting by trained specialist providers. No studies used trained lay providers. Majority of studies used individual format and four used group format.

- Intervention effectiveness: Most studies (uncontrolled) showed favourable results for BA i.e. reduction in scores from pre to post treatment in outcomes of depression and anxiety. Across four RCTs, the effect of BA was large, with an effect size of -0.70 (95% CI -1.20 to 0.20), but high heterogeneity was observed.

- Adaptation to intervention: There was indicators that parental involvement, attractive and developmentally appropriate handout/workbooks, and inclusion of problem-solving skill may be particularly useful for adaption of BA for young people.

This review suggests that there is limited evidence to support BA as effective for young people, and larger trials are needed to provide more reliable findings.

Conclusions

Overall, there was some preliminary evidence for the feasibility of BA interventions; however, there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding its effectiveness for both depression and anxiety.

Strengths and limitations

Owing to high heterogeneity and a small number of studies, the findings from meta-analysis in this review needs to be interpreted with caution. More high quality trials are required to evaluate its effectiveness across conditions and context. Alongside this, issues of optimising the intervention content to ensure maximum efficiency and cost-effectiveness must be considered in future research to aid scalability.

What is behavioural activation? The variety of difference interventions highlighted by this review make it impossible to reliably pool the results across multiple trials.

Behavioural activation as an ‘active ingredient’ in interventions for young people with depression and anxiety – my #ActiveIngredientsMH project

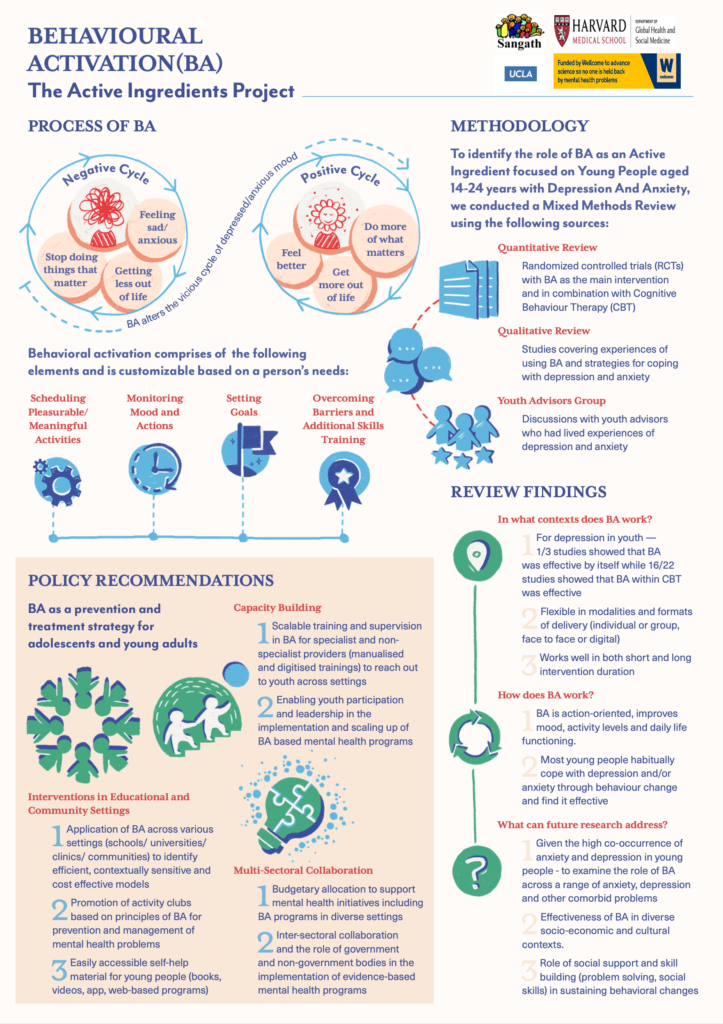

As part of Wellcome Trust ‘Active Ingredient’ commission, we build on the existing review by Martin and Oliver report by examining a broader evidence base on use of BA i.e., studies where BA has been used as a standalone intervention as well as studies where BA has been used along with other elements in interventions for young people (aged 14-24 years) who are experiencing, or at risk of, depression, anxiety or both.

The specific objectives of the current review were:

- To synthesise evidence on the characteristic and impact of interventions where BA has been used.

- To synthesise evidence of acceptability of BA among young people.

To meet above objectives, evidence across the following three sources was synthesized:

- Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating BA as standalone intervention and as an element in multicomponent interventions

- Qualitative studies examining the acceptability of BA as an intervention and coping strategy

- Consultations with a Youth Advisory Group (YAG) with relevant lived experiences

As part of the review, 23 randomised trials were identified:

- BA was used as a standalone intervention in 3 studies and as a constituent element of multicomponent intervention in 20 studies

- Additionally, 37 qualitative and mixed method studies were identified

- Overall, there was preliminary evidence for the effectiveness and acceptability of BA for youth depression

- Across studies and consultation groups, young people emphasised the importance of focusing on individual goals and socio-contextual factors to achieve optimal outcomes through BA

- However, evidence for its use and effectiveness across primary or secondary anxiety conditions was limited

- Overall, the systematic evidence in this age group was limited and more high-quality trials are needed to examine effectiveness of BA as a transdiagnostic technique for depression and anxiety conditions

- Dismantling research examining sequencing and relevance of varied behavioural elements used across BA intervention is needed to establish the ‘active ingredients’ of intervention.

You can learn more about our findings and implications for future research through this infographic.

Statement of interests

Kanika’s team at Sangath in India received funding through the Wellcome Trust Mental Health Priority Area ‘Active Ingredients’ commission to conduct their review of behavioural activation as an active ingredient for treating youth depression.

Links

Primary paper

Martin F, Oliver T. (2019) Behavioral activation for children and adolescents: a systematic review of progress and promise. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2019;28(4):427–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1126-z

Other references

Chu BC, Crocco ST, Esseling P, Areizaga MJ, Lindner AM, Skriner LC. Transdiagnostic group behavioral activation and exposure therapy for youth anxiety and depression: Initial randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2016 Jan;76:65–75,

Dimidjian S, McCauley E. Modular, Scalable, and Personalized: Priorities for Behavioral Interventions for Adolescent Depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2016;23(1):58–61.

Kanter JW, Manos RC, Bowe WM, Baruch DE, Busch AM, Rusch LC. What is behavioral activation?: A review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010 Aug 1;30(6):608–20

McCauley E, Gudmundsen G, Schloredt K, Martell C, Rhew I, Hubley S, Dimidjian S. The adolescent behavioral activation program: Adapting behavioral activation as a treatment for depression in adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2016 May 3;45(3):291-304.

Takagaki K, Okamoto Y, Jinnin R, Mori A, Nishiyama Y, Yamamura T, Yokoyama S, Shiota S, Okamoto Y, Miyake Y, Ogata A. Behavioral activation for late adolescents with subthreshold depression: a randomized controlled trial. European child & adolescent psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1;25(11):1171-82

Tindall L, Mikocka-Walus A, McMillan D, Wright B, Hewitt C, Gascoyne S. Is behavioural activation effective in the treatment of depression in young people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Psychother Theory, Res Pract. 2017;90(4):770–96.

Photo credits

- Photo by Jordan McQueen on Unsplash

- Photo by Gia Oris on Unsplash

- Photo by Anastasiya Romanova on Unsplash