Regular readers will know that there’s a growing call from elf bloggers (and those further afield) to measure and report on the adverse effects of psychotherapy (Mc Glanaghy 2017; Laws & Huda, 2016, Langford & Laws, 2014). This is a simple idea; that we should measure the potential harms of psychotherapy, as well as potential benefits. Information about the harms of mental health treatments are essential to support informed patient decision-making and to help us understand more about how different therapies work.

There are many ways of conceptualising ‘negative effects’ and the meta-analysis published by Cuijpers et al (2018) focussed on deterioration rates; that is, the number of people who reported that their symptoms got worse as the study progressed. This meta-analysis aimed to pull together all information about deterioration rates in randomised controlled trials of psychotherapy for depression.

Any treatment powerful enough to have a positive effect will also have a negative effect. This is true of psychiatric medication, but also of psychotherapies and any other effective treatment.

Methods

The authors described a systematic review of an existing database containing all randomised controlled trials of psychotherapy for depression from four major databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase and Cochrane Library).

The inclusion criteria were:

- Randomised controlled trial

- Adult depression

- Psychological treatment (any language-based intervention between a patient and therapist, including self help which involved a therapist)

- Compared with a control group (i.e. waiting list, usual care, placebo or other inactive treatment)

- Author identified deterioration rates.

Deterioration was measured as the proportion of patients who reported higher scores for depression symptom severity at the end of the study, compared with the beginning.

The reviewers excluded studies of:

- Inpatients

- People with co-morbid mental health difficulties

- Those that focused on maintenance of earlier treatment.

Study quality was assessed using four criteria from the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool; adequacy of the randomisation method (2 items), whether the assessors were blind to the treatment condition and how missing data was accounted for.

All studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in the meta-analysis as follows:

- Risk ratio was calculated for each included study, by dividing the proportion of patients who deteriorated in the intervention group by the proportion who deteriorated in the control group:

- A score of 1 would indicate that the risk was the same in each group

- A score >1 would indicate a higher risk for the intervention group

- A score of <1 indicates a lower risk of deterioration in the intervention group

- This data was pooled and compared across the intervention and control groups

- Other analyses included; subgroup analyses where there were enough studies, sensitivity analyses to investigate the impact of studies with a high risk of bias, meta-regression of continuous variables and a test of publication bias

- Lastly the characteristics of studies that included deterioration rates were compared with similar studies that didn’t.

Results

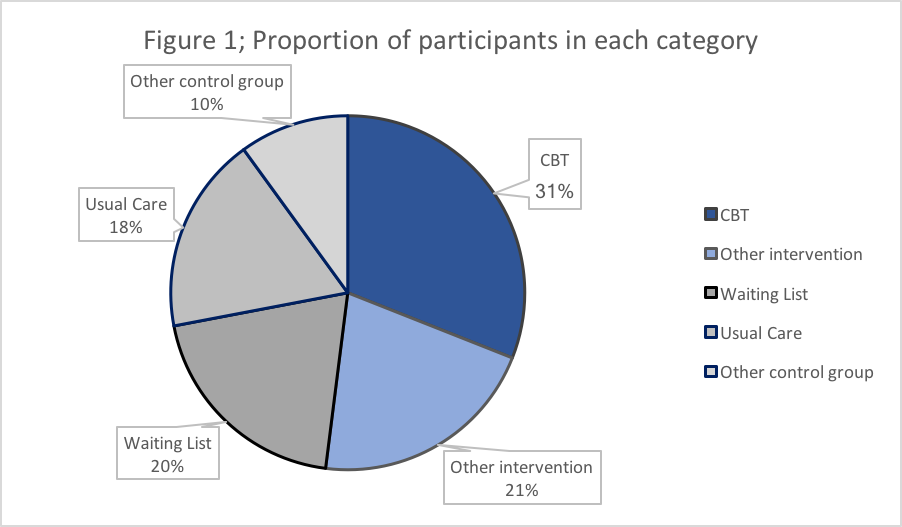

A whopping 18,500 abstracts were reviewed to identify 2,092 full texts for further consideration. Of these, 289 studies were deemed to meet the first four inclusion criteria, and just 6% (n=18) of these reported deterioration rates. Data extraction was validated by 2 independent researchers. The 18 studies provided 23 comparisons of psychotherapy to control groups, involving 1,655 people with depression. The proportion receiving each intervention is shown in Figure 1. Participants were recruited from clinical and community populations and treatment was delivered individually (5 studies), in group settings (7 studies) and as guided self-help (6 studies).

Only three of the 18 studies met all four quality criteria, seven met three criteria, two met two and 6 studies only met one of the quality criteria, indicating that most studies had a high risk of bias.

Meta-analysis results

- A risk ratio of 0.39 was identified for all psychotherapy groups compared to all control groups; meaning the risk of deteriorating in the psychotherapy group was 39% of the risk experienced by having no treatment, or in other words, the risk of deterioration was reduced by 61% with psychotherapy

- Interestingly, very few individual studies reported differences in risk ratio, however when the data was pooled in the meta-analysis the effect was recognised as statistically significant. This may be explained by the size of the studies; some studies may have been too small (and therefore underpowered) to detect the difference

- The meta-regression indicated the risk ratio was not related to differences in the definitions used to measure depression, the type of therapy or control group in the studies, or intervention format (that is, individual or group or self- help)

- There was no evidence of publication bias, and there was little evidence of heterogeneity; meaning that there was little variation in the outcomes reported by each study

- There was also no evidence that studies with a high risk of bias had different results, however the authors acknowledged that there may have been too few studies with a low risk of bias to be sure about this.

- Lastly, when comparing the studies that met all inclusion criteria except deterioration and the 18 included in this analysis, no differences in study design or samples were identified. The reasons why some reported deterioration and others didn’t is unclear.

This well conducted meta-analysis suggests that psychological treatments for depression seem to reduce the risk for deterioration, when compared to controls.

Conclusions

In summary, this meta-analysis identified that undertaking psychotherapy may reduce the risk of deterioration for depression symptoms, however this is in the context of an evidence base that mostly excludes deterioration as an outcome.

Strengths and limitations

This study is a great example of how meta-analysis can illuminate an issue where randomised controlled trials may not. This is especially relevant where trials have small samples or are measuring a rare phenomenon. This highlights the importance of including data on deterioration in randomised controlled trials of psychotherapy, even if it appears to be non-significant. We cannot assume there are no negative effects in the absence of data. Indeed, in this analysis, it is recognised that no intervention carries a greater risk than psychological intervention.

As with all meta-analyses, there are some limitations and caveats:

- The quality assessment of the included studies identified that a large proportion of the studies had a high risk of bias, which may impact the findings

- The ‘other intervention’ group included a range of different therapies; cognitive-reminiscence therapy, cognitive therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, behavioural activation, psychoeducation and interpersonal therapy. While there was no evidence of heterogeneity, and statistically it appears that there were no differences across therapy styles, it is possible that different therapies may have had different effects that were not picked up due the small number of studies

- Similarly, the samples in each study were also diverse, with some studies including only women with postpartum depression and others included only elderly people; no evidence of heterogeneity was found, however the small sample may have reduced the likelihood of finding a difference if there is one

- Lastly, the inclusion of 3 different therapy formats (individual, group and self-help) may also obfuscate the differential impacts on outcomes. The interpersonal relationship with the therapist is an important factor in the potential for adverse effects, including deterioration (Berk & Parker, 2009; Parry et al., 2016). From the clinical perspective it is recognised that there is a qualitative difference between the interpersonal experience across different formats, which may be important to account for in future meta-analyses.

This research highlights the importance of including data on deterioration in randomised controlled trials of psychotherapy, even if it appears to be non-significant. We cannot assume there are no negative effects in the absence of data.

Implications for practice

- The results appear promising for clinical practice; in studies that report deterioration rates, psychotherapy for depression (mostly CBT) is less likely to lead to a deterioration than usual treatment/being on a waiting list

- However, this is based on data from just 6% of potentially relevant studies and does not account for the other potential adverse effects of psychotherapy that are increasingly being recognised (Rozental, Kottorp, Boettcher, Andersson & Carlbring, 2016 as reviewed in Mc Glanaghy, 2017)

- This well conducted meta-analysis highlights a gap in the reporting of negative effects of psychotherapy in general, but it also signifies a really important step in the right direction!

Only 6% of all trials (comparing psychotherapy to controls) report deterioration rates. This needs to change.

Conflict of interest

Dr Edel Mc Glanaghy has recently completed a Delphi study of the Adverse Effects of Psychotherapy.

Links

Primary paper

Cuijpers P, Reijnders M, Karyotaki E, de Wit L, Ebert DD. (2018) Negative effects of psychotherapies for adult depression: A meta-analysis of deterioration rates. Journal of Affective Disorders, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.050

Other references

Berk, M. & Parker, G. (2009). The elephant on the couch: side-effects of psychotherapy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 787-794.

Parry, G. D., Crawford, M. J. & Duggan, C. (2016). Iatrogenic harm from psychological therapies- time to move on. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208, 210-212. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.163618

Rozental, A., Kottorp, A., Boettcher, J., Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. (2016). Negative effects of psychological treatments: an exploratory factor analysis of the Negative Effects Questionnaire for monitoring and reporting adverse and unwanted events. PLoS ONE 11(6): 1–22. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157503

Photo credits

- Photo by Riccardo Mion on Unsplash

- Photo by Kari Shea on Unsplash

- Photo by Brandon Wong on Unsplash

- Peter CC BY 2.0

- By Amman Wahab Nizamani [CC BY-SA 4.0 ], from Wikimedia Commons