How much evidence is there that “Headspace” or “get Happy” actually make us happier?

The last few years has seen a proliferation of mental health apps purporting to help treat depression. If true, they may present an unprecedented opportunity; after all, the affordability, accessibility and scalability of apps make them a potentially transformative option for the delivery of interventions to prevent and treat depressive symptoms.

With the recent dramatic rise in smartphone ownership, hundreds of mental health apps are downloaded every day, but there is a paucity of robust evidence in an unregulated market. Very few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been carried out, and there is a growing need for a set of evidence-based principles to guide not only selection but app development.

The authors of a recent open access paper (Firth et al, 2017) have conducted the first meta-analysis to evaluate smartphone apps for depressive symptoms and in doing so, among other goals, seek to address a “duty of care” towards potential future users.

The affordability, accessibility and scalability of apps make them a potentially transformative option for the delivery of interventions to prevent and treat depressive symptoms.

Methods

In their meta-analysis, the authors used the PRISMA statement and the same protocol they used for an earlier meta-analysis of apps for anxiety symptoms (Firth et al, 2017b).

They searched multiple databases using the PICO framework and by checking through reference lists of selected articles for further studies.

They selected English-language RCTs only, looking at smartphone interventions, which included depressive symptoms as one of the outcome measures, across a range of diagnoses and settings and measured using multiple validated measures.

Studies with both active controls (apps or links to websites), and inactive controls, primarily waitlist controls were included.

Three independent investigators checked study eligibility. Study data and characteristics were extracted and analysed to measure the overall effect size. The authors carried out a quality assessment of included studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment tool, a funnel plot to check for publication bias, and tested for heterogeneity.

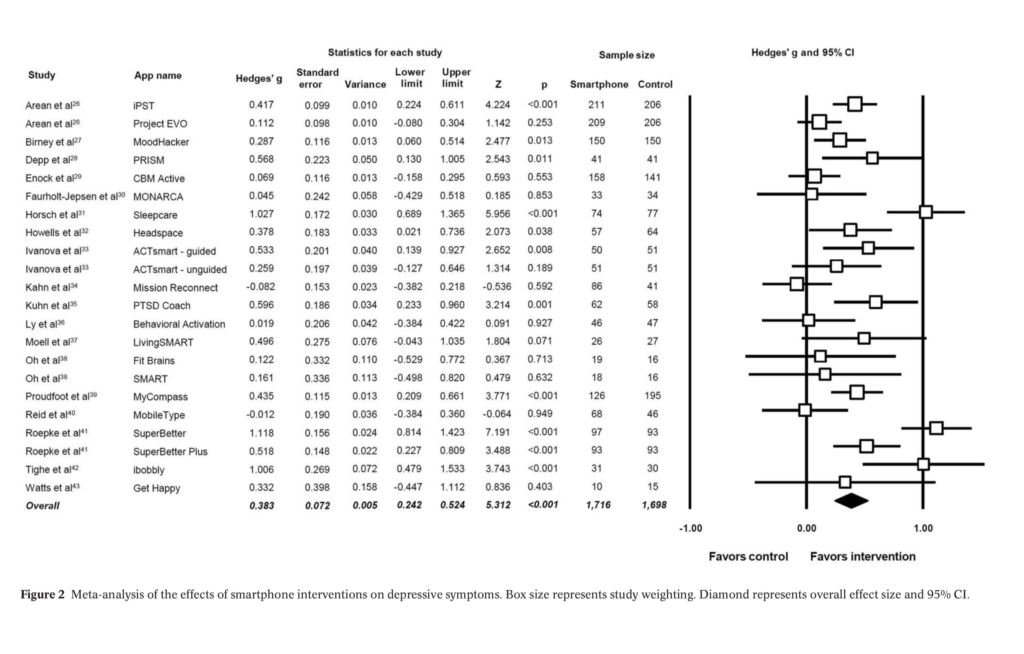

To measure effect size, the authors calculated a Hedge’s g for each intervention and then pooled the statistic across all studies to get an overall effect size.

Results

- 18 RCTs were included in the analysis, evaluating 22 apps, with a total of 3,414 participants across studies

- Interventions lasted between 4 and 24 weeks

- The most common limitation was inadequate blinding of participants

- Depressive symptoms were measured as a primary outcome in 12 studies and as secondary outcomes in 6 studies

- 13 studies used intention to treat analysis or reported full outcome data

- The 18 included studies were statistically heterogeneous (p<0.01), with no evidence of publication bias

- A range of different assessment tools were used to measure depressive symptoms, including the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory II and the Patient Health Questionnaire.

The main findings

Overall, the meta-analysis found a significant small to moderate positive effect for smartphone apps on depressive symptoms compared to controls (g=0.383, 95% CI: 0.24 to 0.52, p<0.001), but this was restricted to only those with self-reported mild to moderate depression (g=0.518, p<0.001, 95% CI: 0.28 to 0.75).

Active and inactive controls

- 13 out of the 18 studies included waitlist controls in their control arm (inactive control studies)

- 12 out of 18 studies included an active control arm

- 5 used an alternative app

- 3 a computerised alternative

- 1 a paper and pencil intervention

- 1 regular smartphone use

- 1 a face-to-face behavioural intervention

- Effect sizes were found to be larger when smartphone interventions were compared to an inactive control, with an effect size of g=0.558 (95% CI: 0.38 to 0.74), indicating a moderate effect on depressive symptoms.

- In active control studies, the pooled effect size on depressive symptoms was significant but small g=0.216 (95% CI: 0.10 to 0.33).

Clinical and non-clinical populations

- 6 studies were conducted in a clinical population and 12 in a non-clinical population

- 7 studies used a population with either self-reported or clinically confirmed depression

- In subgroup analysis of studies with mood disorder inclusion criteria, the authors found no significant effect in people with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder or anxiety disorders. The only significant effect was in self-reported mild-to-moderate depression (g=0.518, p<0.001, 95% CI: 0.28 to 0.75).

App characteristics

Surprisingly, interventions using human feedback in addition to the digital intervention was not statistically significant (g= 0.137, p= 0.214).

Subgroup analysis of intervention features found that the effect size of the intervention was stronger in apps that provided in-app feedback such as progress scores (g=0.534, 95% CI: 0.26 to 0.81)

Interventions delivered exclusively through the app showed a larger effect size (g=0.479, p=<0.001) than those delivered with interventions outside of the app (g=0.241, p=0.002) although this difference was not significant (p=0.07).

This meta-analysis found a significant small to moderate positive effect for smartphone apps on depressive symptoms compared to controls, but this was restricted to only those with self-reported mild to moderate depression.

Conclusions

Overall the results suggest a possibly promising role for smartphone apps in the prevention and treatment of sub-clinical, mild and moderate depressive symptoms in the general population. However, efficacy in clinical populations and for major depressive disorder remains unclear.

Strengths and limitations

While only English language studies were selected, the search strategy, selection criteria and analytic procedures were robust and adhered to established protocols.

However, the heterogeneity of the 18 interventions makes it difficult to draw clear conclusions about which app characteristics and which psychological interventions were more effective than others. It also exacerbates the difficulty in isolating the role of “digital placebo”; the various non- specific digital features inherent to the experience of app use itself rather than it’s psychotherapeutic content (Torous et al, 2016). Only 6 of the studies with active controls were an app, which may explain why the effect size shrinks when compared to inactive (non-app) controls.

Implications for future research

Digital placebo need not be a bad thing, but if we agree in principle that we want to be able to look at these studies and create guidelines for future evidence-based app development, it is more important to know which aspects of the apps are effective, rather than if App A was better than App B.

Future researchers may need to confront the possibility that RCTs may be an impractical and ineffective study design to evaluate digital interventions (Pham et al, 2016). RCTs take time and apps need to keep up with the pace of innovation or risk becoming obsolete before they are implemented.

Another drawback is that the RCTs cannot capture engagement with the app over longer time periods, the ‘novelty effect’ may give a false impression about app usage in the first few months, but downloaded apps if unused are no longer of therapeutic value to the user.

Overall however, this study provides robust evidence that apps have a role in treating mild to moderate depressive symptoms and therefore may have a potentially powerful role in prevention. What we need now is to think about how best to use these findings to develop evidence-based guidelines to guide both future app development and user selection. Efficacy in clinical populations however, remains to be seen.

What are the ‘active ingredients’ of digital apps for people with depression?

Links

Primary paper

Firth J, Torous J, Nicholas J, et al. (2017) The efficacy of smartphone‐based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):287-298. doi:10.1002/wps.20472.

Other references

Firth J, Torous J, Nicholas J, Carney R, Rosenbaum S, Sarris J. (2017b) Can smartphone mental health interventions reduce symptoms of anxiety? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2017 Aug 15;218:15-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.046. Epub 2017 Apr 25.

Torous J, Firth J. (2016) The digital placebo effect: Mobile mental health meets clinical psychiatry. The Lancet Psychiatry. 3. 100-102. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00565-9.

Pham Q, Wiljer D, Cafazzo JA. (2016) Beyond the Randomized Controlled Trial: A Review of Alternatives in mHealth Clinical Trial Methods. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(3), e107. http://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.5720

Photo credits

- Photo by Attentie Attentie on Unsplash

- Photo by Omar Prestwich on Unsplash

[…] they featured a blog on a 2017 meta-analysis by Firth et al, published in the prestigious journal World Psychiatry […]

I was looking forward to this blog and the meta-analysis it discusses, but digging deeper into the Firth meta-analysis and the primary studies it includes I was left with a mixture of disappointment and confusion. This meta-analysis is timely and has a lot going for it – but it could’ve been so much better.

I wrote a blog (well, a rant really) on my findings regarding the meta-analysis and its primary studies here:

http://robinkok.eu/2018/03/23/about-firths-apps-for-depression-meta-analysis/