Imagine for a moment a scenario where a concerned parent takes their thirteen year old to a mental health professional. The teenager has come out to them as transgender, is struggling in school, is easily overwhelmed by anxiety, and is contemplating suicide. Now, consider how this parent might react if their child told them their therapist assigned them to play a video game for an hour every day. Maybe even imagine the thirteen-year-old’s expression when their therapist actually did.

We are in a world where most young people seem forever absorbed in their phones, video games, and laptops. Most of us seem hopelessly disconnected from face to face interaction. Youth, particularly those whose sexual orientation and gender identity differs from heterosexual, cisgender norms, are struggling with higher rates of bullying, aggression, truancy and other social issues. Research links these struggles to increasing rates of mental health diagnoses and other serious consequences such as drop-out, homelessness, addiction and suicide. Under these bleak conditions, it is difficult to imagine a mental health professional encouraging a transgender teenager to plug-in even more.

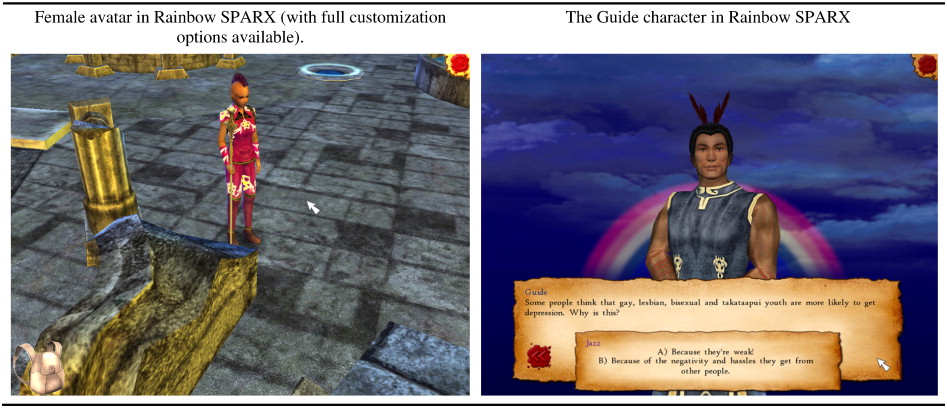

Enter Rainbow SPARX, an interactive video game designed in New Zealand. Rainbow Smart Positive Active Realistic X-Factor (SPARX) is a seven module, computerised Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (cCBT) adapted specifically for sexual minority youth from the original SPARX cCBT, which we blogged about here. The fantasy-based intervention consisting of seven modules, is the only e-therapy focused on assisting LGBT+ youth learn coping skills for depression. Given a recent dramatic increase in e-therapy development, this is surprising.

Both a randomised controlled trial (n= 143) of SPARX (Merry, et al., 2018) and an exploratory study (n = 21) of Rainbow SPARX (Lucassen, et al., 2015) have shown these interventions to have promise in reducing depressive symptoms among participants. SPARX is now available on the internet for free to anyone who has a New Zealand based internet address.

As these two e-therapies continue to be refined, developers have begun to explore the translatability of SPARX and Rainbow SPARX to other audiences. Recently, a group of researchers conducted a series of focus groups in the United Kingdom to determine the cultural adaptability and receptiveness of LGBTQ+ youth to the Rainbow SPARX cCBT intervention (Lucassen, et al., 2018). Researchers had two main research objectives:

- To explore how UK LGBTQ+ youth use the internet to help with their mental health symptoms

- To see the extent to which LGBTQ+ youth, their guardians, and mental health professionals see Rainbow SPARX as potentially supportive of LGBTQ+ youth mental health in the UK.

Previous research tells us that LGBT+ people experience higher rates of mental illness compared with the general population.

Methods

Participants for this study were recruited through advertisement in closed-groups on social media platforms and through existing LGBTQ+ youth groups in major UK cities that were known or recommended to the researchers. The qualitative study included 21 LGBTQ+ youth (ages 15-22) and 6 health and social care professionals.

Over the course of the study, the researchers conducted;

- 3 focus groups consisting of LGBTQ+ youth and the LGBTQ+ staff responsible for them

- 5 structured interviews with 1 LGBTQ+ identifying youth and 4 professionals.

The protocols, for both the focus group and individual interviews, consisted of age-appropriate informed consent, exposure to the first Rainbow SPARX module, and open ended questions. Participants were also asked to complete a brief demographics questionnaire at the end of their group or individual interview.

Rainbow SPARX is a 7 module, computerised CBT interactive fantasy-based video game, which teaches coping skills for depression to sexual minority youth.

Results

A Generalised Inductive Approach (GIA) method using Microsoft Excel was used for data analysis of the transcribed focus groups and individual interviews. Analysis demonstrated three main domains:

- Use of the internet and being on the Web

- Computer games and serious gaming

- The wellbeing needs and support of LGBTQ+ youth.

General results were mixed across domains. While some LGBTQ+ youth found the game to be outdated and were put off by the colloquial examples (Rainbow SPARX utilises some Maori (i.e. indigenous New Zealand) references), others seemed to engage and felt the serious game would be helpful.

Some LGBTQ+ youth found the Rainbow SPARX game to be outdated and were put off by the colloquial examples, but others felt the serious game would be helpful.

Internet use and being on the Web

Regarding the first emergent theme, most youth recognised the ubiquitous nature of the internet and appeared savvy and adept at navigating this resource. They understood some areas of the internet to be useful while others fraught with predatory or unhelpful sites, which exacerbated issues where LGBTQ+ youth struggled (for example sites which glamorise self-harm). They also valued the internet as a place for broader social connection.

Computer games and serious gaming

Most of the participants were familiar with numerous gaming platforms and had engaged in different levels of gaming depending on preference for level of violence, graphic interface, and method of access (i.e. Xbox, desktop, mobile device, etc.). While some participants commented they would “definitely play [Rainbow SPARX]” many participants identified issues with the game falling short regarding issues specific to sexual and gender expansive youth (example: requiring an avatar to be binary, i.e. male or female). Furthermore, there was discussion regarding the game feeling slow and not in keeping with the quality of other games they were accustomed to playing.

Wellbeing needs and support of LGBTQ+ youth

The third theme from the GIA of the transcriptions demonstrated both professional and youth participants recognised the dual stigma faced by LGBTQ+ youth with mental health struggles. While a serious game like Rainbow SPARX could assist with reducing barriers created by this duality, many participants had concerns with the accessibility, outdated nature, and unmonitored nature of a cCBT intervention.

Many participants identified issues with the game falling short regarding issues specific to sexual and gender expansive youth.

Conclusions

This exploratory study set out with two main research questions. The results support an understanding that while LGBTQ+ youth are able to navigate the internet quite well, there are still significant barriers to locating quality resources (such as an LGBTQ+ specific e-therapy) and concerns for negative social interaction (i.e. predatory behaviour and cyberbullying).

Interestingly, while all professional participants indicated they would recommend Rainbow SPARX as an intervention for an LGBTQ+ youth who was “feeling down,” only 8 of the 21 youth participants said they would be likely to use this serious game in this context.

There are still significant barriers for LGBTQ+ youth to find useful resources and e-therapy online.

Strengths and limitations

As is common in this level of exploration with underserved populations, this study had limitations. These limitations included recruitment of participants, sample size, generalisability, and exposure to the product (only one person in the focus group played while the others watched).

The strengths of the study include a thorough exploration of recontextualising an existing cCBT intervention, gaining insight into LGBTQ+ youth utilisation of serious games and the internet, and a deeper understanding of which elements of e-therapy and serious games are pivotal to engagement.

Implications for practice

- While it is highly unlikely that any one serious game such as Rainbow SPARX can assist all youth across cultures, developmental stages, and gender and sexual diversities, this study advances our understanding of these multilayered issues.

- Computerised CBT and other e-therapies may be helpful when used in tandem with other resources or as a gateway to more intensive mental health services.

Computerised CBT and other e-therapies may be helpful for LGBTQ+ youth, when used in tandem with other resources.

Statement of interests

None declared.

Links

Primary paper

Other references

Lucassen, M. F., Merry, S. N., Hatcher, S., & Frampton, C. M. (2015). Rainbow SPARX: A novel approach to addressing depression in sexual minority youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 203-216.

Lucassen, M., Samra, R., Iacovides, I., Fleming, T., Shepherd, M., Stasiak, K., & Wallace, L. (2018). How LGBT+ Young People Use the Internet in Relation to Their Mental Health and Envisage the Use of e-Therapy: Exploratory Study. JMIR Serious Games, 6(4).

Merry SN, Stasiak K, Shepherd M, Frampton C, Fleming T, Lucassen MF. The effectiveness of SPARX, a computerised self help intervention for adolescents seeking help for depression: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ 2012 Apr 18;344:e2598-e2516 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2598] [Medline: 22517917]

Strauss, P., Morgan, H., Toussaint, D. W., Lin, A., Winter, S., & Perry, Y. (2019). Trans and gender diverse young people’s attitudes towards game-based digital mental health interventions: A qualitative investigation. Internet Interventions, 100280.

Can gamified cCBT prevent depression in secondary school students?

Photo credits

- Photo by Ramón Salinero on Unsplash

- Photo by Tanushree Rao on Unsplash

- Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

- Photo by John Schnobrich on Unsplash

- Photo by Leon Seibert on Unsplash