People affected by mental illness have historically experienced a sense of powerlessness (Linhorst & Eckert, 2003), often being denied a voice in decisions made about their treatment (WHO, 2010). Fortunately, the importance of empowerment (i.e., the process of encouraging people to take control of their health (Calvillo et al., 2015)) is increasingly recognised in health policies and legislation (Foot et al., 2014). This has led to greater service user involvement at all stages of delivery, including the self-management of chronic conditions.

The importance of self-management knowledge and skills is particularly important in schizophrenia (e.g., Zou et al., 2013). Worryingly, young people with schizophrenia may be less likely to attend their appointments (e.g., Coodin et al., 2004), leaving them with fewer opportunities to learn how to effectively manage their condition (Terp et al., 2018).

It is clear that more innovative approaches are needed. As interest in mental health applications (apps) continues to increase (Torous et al., 2018), might this be the key to helping young people manage their mental health?

Using a qualitative framework, Terp and colleagues (2018) explored how young adults with a recent diagnosis of schizophrenia used and perceived a smartphone app (MindFrame) as a way of empowering them with the everyday management of living with their condition.

Could apps help young adults with severe mental illness manage their mental health?

Methods

Participants and settings

- The study took place in the OPUS outpatient clinic in Denmark.

- OPUS was open to young people aged 18 to 36 years who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia within the last two years.

- Eligible participants included service users who had used the app in the intervention period and were willing talk about their experiences in the qualitative evaluation study.

App

- The MindFrame app was developed in collaboration with young adults with a recent diagnosis of schizophrenia, healthcare providers (HCPs), a researcher, and software designers.

- Examples of MindFrame’s features include a self-assessment tool, an action plan, and a medication overview.

Topics of interest

- A combination of open-ended and close-ended interview schedules were used to explore the concepts of power and empowerment.

Analysis

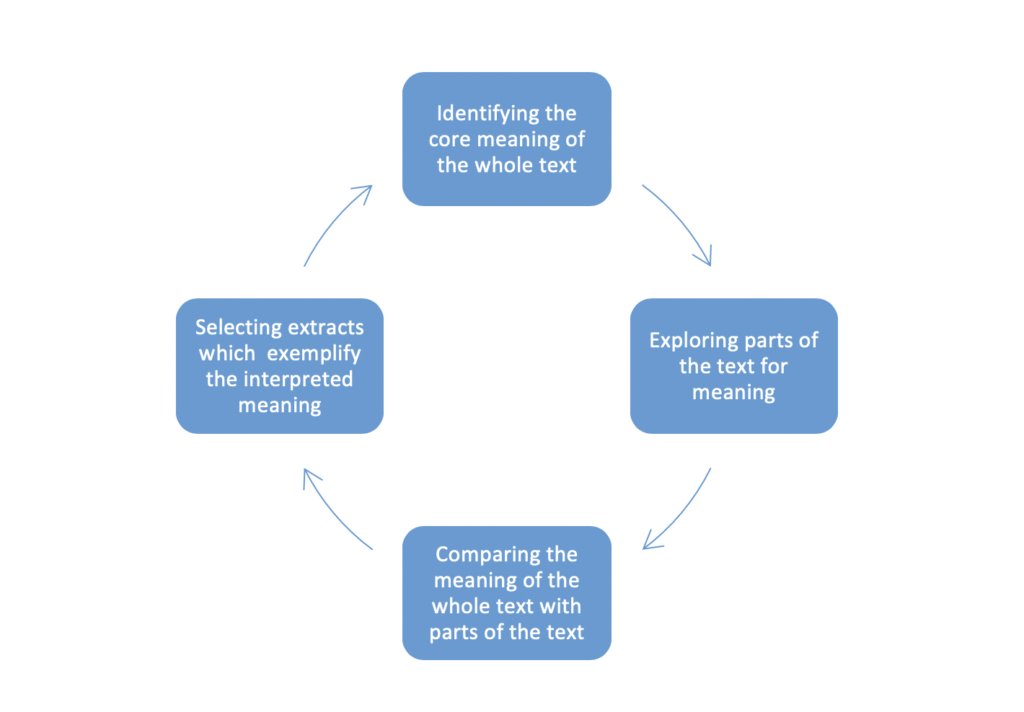

- The analysis was guided by Fleming et al.’s (2003) four-step iterative process based on Gadamer’s (1989) interpretative hermeneutical approach (Figure 1). This helped uncover a deeper meaning of the data.

Figure 1: An overview of the four-step iterative process.

Results

Participants

- Out of the 27 young people who used MindFrame in the intervention period, 13 took part in the qualitative interviews.

- The qualitative sample consisted of 4 males and 9 females with a mean age of 24.8 years.

Use of MindFrame

- The MindFrame app was described as intuitive and easy to use.

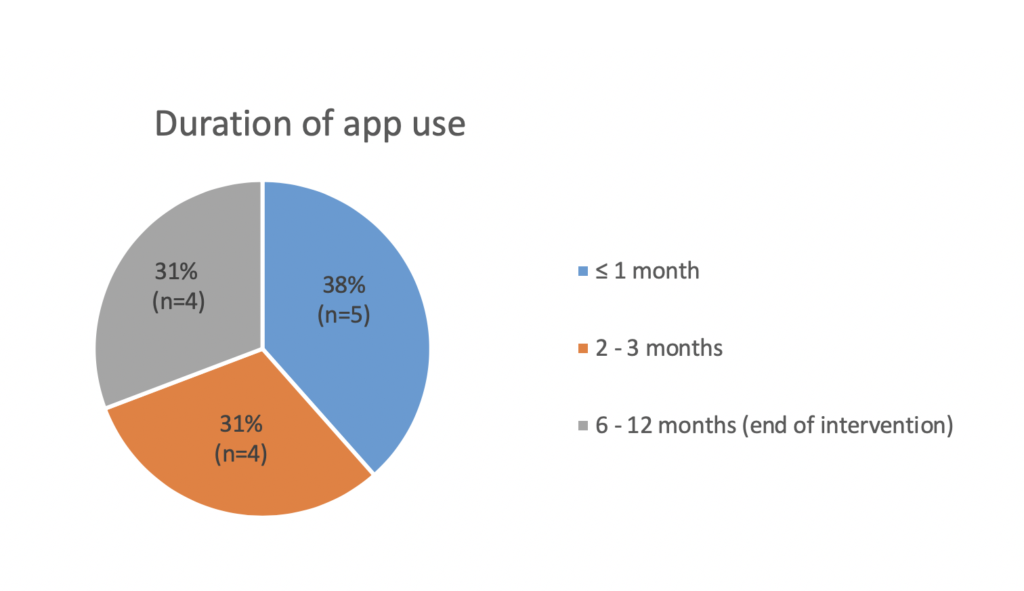

- As seen in Figure 2, participants used MindFrame for different periods of time, based on their needs and preferences.

- Participants stopped using the app for different reasons (e.g., boredom, tiredness).

Figure 2: An overview of the participants’ duration of app use.

Perceptions of MindFrame

The analysis identified the potential empowering and disempowering aspects of the MindFrame app:

1. The potential of MindFrame to empower young people to stay on track with their condition

The MindFrame app was perceived as an empowering tool, provided this app was used in a consistent manner with the HCPs for more than a month. Use of the MindFrame app may:

- Remind young people to take their medication more regularly

- Help young people understand the impact of irregular medication intake and encourage appropriate action (n=1)

- Facilitate a quick response to early warning signs

- Assist young people with identifying effective coping skills

- Help young people keep track of their mental health and progress

- Enable HCPs to be more responsive to young people’s needs

- This allowed young people to receive appropriate help in a timely manner

- Help understand reasons behind fluctuating mental states

- Facilitate the evaluation on the effectiveness of behaviour change

- Increase young people’s confidence and independence with their health management.

2. The potential of MindFrame to disempower young people from feeling certain and secure

Despite these positive findings, MindFrame may also have some disempowering elements, which can affect young people’s sense of certainty and security. Some participants expressed:

- Concerns about being under regular surveillance (n=3)

- Fears that this surveillance could result in involuntary restraints and hospitalisations (n=3)

- Two out of three participants felt less fearful over time

- One participant remained concerned and subsequently did not report his true mental state on his bad days in order to appear better (n=1)

- Increased feelings of uncertainty in response to notifications of the app (n=2), including:

- Occasional feelings of stress in response to alerts about all of the changes in their mental states. This in turn made them feel less sure about whether their condition was getting worse

- Mismatches between their interpretation of their mental state (e.g., feeling fine) and notifications from the app (being advised to take care). This in turn made participants feel in doubt about what to think and whether or not to take action.

This small study suggests that some young adults diagnosed with schizophrenia are amenable to use a smartphone app to monitor their health, manage their medication, and stay alert of the early signs of illness exacerbation.

Conclusions

Smartphone apps which allow young people with schizophrenia to monitor their health, manage their medication, and notify young people of early warning signs, can empower them to manage their condition.

Fears and uncertainties associated with the use of app-based care may affect engagement with the app, and this needs to be explored further.

Strengths and limitations

I really enjoyed reading this paper. Using a qualitative approach provided a more in-depth understanding of young service users’ experiences, particularly as their perspectives on this research topic had not yet been explored. I was also pleased to see that young people played a key role in the design of the MindFrame app, which better ensured the app reflected their unique needs.

However, this paper had some limitations. The authors identified potential sources of bias (e.g., recall bias). It was also acknowledged that the sample may not have been representative of the wider population of young people with a recent diagnosis of schizophrenia. This limits the generalisability of findings.

This paper also required more clarity in some places. For example, it was unclear to me who was involved in the analysis of the data. An analysis process involving multiple researchers for example, may help broaden understanding and increase the validity of findings (Guion et al., 2011). More detail was also required in the reporting of some of the findings. For example, the study clearly described the number of people who reported each negative experience and perception. It would have been useful if the same level of detail was provided to reports of positive experiences and perceptions. This would help put the findings in perspective.

The sample of people in this Danish study may not have been representative of the wider population of young people with a recent diagnosis of schizophrenia, which limits the generalisability of findings.

Implications for practice

This study demonstrated the various ways in which the smartphone apps can improve the quality of care young people receive. It is therefore encouraging to see that the app platform (Monsenso) is being delivered more widely in clinical settings (e.g., in the NHS Foundation Trust of Central Northwest London). However, given that this app is not publicly available, there is a clear need for publicly accessible apps to be subjected to the same level of rigorous testing, in order to understand their potential clinical utility and effectiveness.

The results showed that 51% (50/98) of eligible young people declined to participate in the intervention study and 38% of participants stopped using the app within a month. This suggests that smartphone apps for mental health care may not be universally acceptable to young people with schizophrenia. Its use should therefore be considered on a case-by-case basis and relies on the support of HCPs who may help alleviate some of the fears and concerns felt by service users. The findings also indicated that some young people may not feel comfortable with reporting their actual mental state. Smartphone data should therefore be interpreted with caution and supplemented with additional sources of information (Fennig et al., 1994).

There’s a clear need for publicly accessible health apps to be subjected to rigorous testing, in order to understand their potential clinical utility and effectiveness.

Conflicts of interest

I am currently completing a PhD which similarly focuses on the use of mental health apps for young people.

Links

Primary paper

Terp, M., Jørgensen, R., Laursen, B. S., Mainz, J., & Bjørnes, C. D. (2018). A Smartphone App to Foster Power in the Everyday Management of Living With Schizophrenia: Qualitative Analysis of Young Adults’ Perspectives. JMIR mental health, 5(4).

Other references

Calvillo, J., Roman, I., & Roa, L. M. (2015). How technology is empowering patients? A literature review. Health Expectations, 18(5), 643-652.

Coodin, S., Staley, D., Cortens, B., Desrochers, R., & McLandress, S. (2004). Patient factors associated with missed appointments in persons with schizophrenia. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(2), 145-148.

Foot, C., Gilburt, H., Dunn, P., Jabbal, J., Seale, B., Goodrich, J., … & Taylor, J. (2014). People in control of their own health and care. London: King’s Fund

Fennig, S., Kovasznay, B., Rich, C., Ram, R., Pato, C., Miller, A., … & Phelan, J. (1994). Six-month stability of psychiatric diagnoses in first-admission patients with psychosis. The American journal of psychiatry, 151(8), 1200.

Gadamer, H. G. (1989). Truth and Method Revised Edition. New York: Sheed & Ward.

Guion, L.A., Diehl, D.C., & McDonald, D. (2011). Triangulation: Establishing the Validity of Qualitative Studies. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

Linhorst, D. M., & Eckert, A. (2003). Conditions for empowering people with severe mental illness. Social Service Review, 77(2), 279-305.

Torous, J., Luo, J., & Chan, S. (2018). Mental health apps: What to tell patients. Current Psychiatry, 17(3), 21.

World Health Organization. (2010). User empowerment in mental health: A statement by the WHO Regional Office for Europe- Empowerment is not a destination, but a journey. Copenhagen: WHO

Zou, H., Li, Z., Nolan, M. T., Arthur, D., Wang, H., & Hu, L. (2013). Self‐management education interventions for persons with schizophrenia: A meta‐analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(3), 256-271.

Photo credits

- Photo by Glen Anthony on Unsplash

- Photo by Oleg Magni on Unsplash

- Photo by ROBIN WORRALL on Unsplash

- Photo by Jade Masri on Unsplash

- Photo by Sebastian Hietsch on Unsplash