There is a massive gap between how common mental health conditions are and the resources we have available to provide services to all that need it. An approach to improve access to services and to provide people with the right type of intervention at the right time is the introduction of stepped care models. The idea is to match people’s needs to the intensity of the intervention. An example of this model is the one described by NICE (NICE, 2011). The UK has implemented this model in its increased access to psychological therapies programme (IAPT) at a national scale. IAPT services offer evidence-based non-pharmacological interventions from low intensity self-help to face to face therapy to people with depression, anxiety, and related conditions. It is still not clear if it’s cost effective (Mukuria, 2013).

This problem has dominated my working life for the past 8 years. By way of full disclosure, I run a social impact company that develops applications for common mental health conditions. When we started, my partners and I believed that the only way to close that gap between resources and prevalence was to use evidence-based digital interventions as a step before people engage with therapists. We also thought that apps could be used during therapy to make it more cost effective. Please don’t misunderstand, this is not about stopping people from accessing therapy by giving them an app instead. This is about offering people effective alternatives that can do a good job for them without having to wait unnecessarily.

Derek Richards and colleagues (from Silver Cloud Health and Trinity College, Dublin) published a study in NPJ in June 2020 (Richards, 2020) that addresses this question using a pragmatic randomised controlled trial design looking at both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

There is a massive gap between how common mental health conditions are and the resources available to provide services.

Methods

Population: The researchers invited 464 people from an existing IAPT service to participate. 361 met all inclusion criteria which largely mirrored normal IAPT eligibility criteria. Median age was 29 and 70% were female.

Researchers used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), a diagnostic interview, as part of their screening – 80% of participants met criteria for a diagnosis and 70% met the threshold for caseness using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ9) (scores over 9) and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD7) (scores over 7).

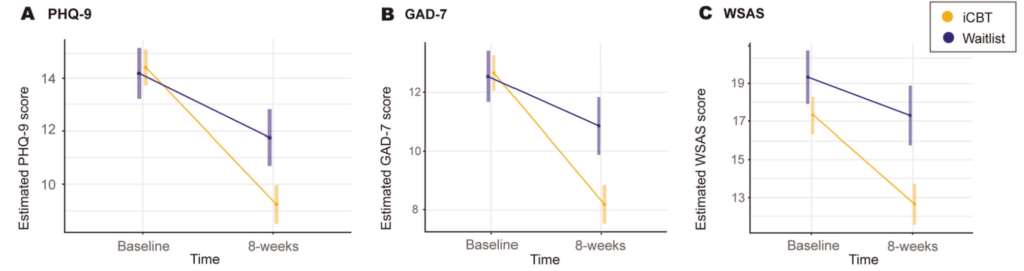

Outcome measures: The authors selected the PHQ9, the GAD7 and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) as their main outcome measures. This was measured at baseline and 8 weeks. They also reassessed participants using the MINI at 3 months and looked at meeting criteria for any given diagnosis as an additional outcome measure. They also followed up participants at 6 months, 9 months and 12 months post intervention.

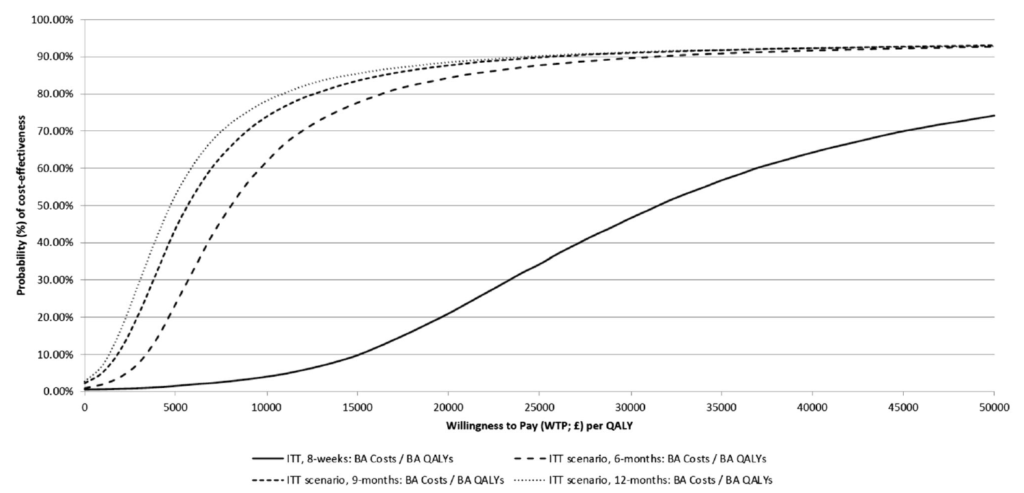

To evaluate cost-effectiveness, they used the EuroQoL Five-Dimension Five-Level (EQ-5D-5L) that yields quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and a modified Client Service Receipt Inventory that measures use of care resources. The probability of cost-effectiveness was calculated dependent on a willingness to pay £30,000 per QALY.

Randomisation: The authors used an established algorithm and an external team to produce the randomisation. The psychological wellbeing practitioners (PWPs) that carried out the support and assessment were not blinded to allocation.

Analysis: The description of the analysis was comprehensive, and it included how the intention to treat analysis was carried out and the rationale for using various scenarios and statistical methods.

Intervention: The internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy used in the study was SilverCloud Health’s ‘Space from Depression’, ‘Space from Anxiety’ and ‘Space from Depression and Anxiety’. PWPs provided 6 reviews online lasting 15 minutes each.

Results

Effectiveness

There were statistically significant improvements for all outcome measures. The endpoint PHQ and GAD scores were still in the caseness range for the intervention group.

Follow-up

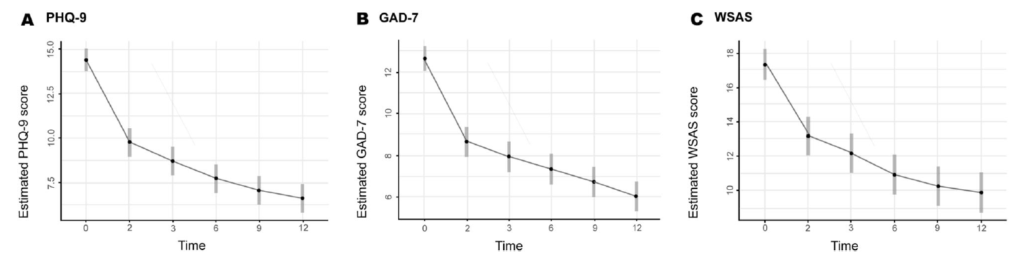

At follow up the authors reported maintained or improved symptom levels across all follow-up time-points. Fig 2 shows the estimated values for all three outcome measures only in the intervention arm. These values are statistically inferred from those observed based on 8-week linear mixed models as per the intention to treat analysis.

Clinically significant change

There were significantly more recoveries in the intervention arm (46.4% vs 16.7). Of those that completed the M.I.N.I at 3 months, 56.4% no longer met criteria.

Cost-effectiveness

To produce probabilities of cost-effectiveness the authors created 4 models evaluating cost effectiveness at 8 weeks, 6 months, 9 months and 12 months from the time of the intervention. All 4 models were run for a willingness to pay £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY (8 models in total). They discovered that the probability of cost-effectiveness increases as the time horizon increases. At 12-months this ranges from 91.2% to 92.0% at £30,000, or 88.5 to 90.1% at £20,000, per QALY gained. See fig 3 below.

Conclusions

- This large RCT shows that iCBT for anxiety and depression in the context of an IAPT service can be effective and cost effective as a standalone intervention

- The probability of it being cost effective grew with the length of the time horizon in the different scenarios. This is important to note as cost-effectiveness analysis in this context might not extend the assessment beyond the 8-week treatment period

- The intervention also demonstrated an improvement in function, not just symptoms.

This large RCT shows that iCBT for anxiety and depression in the context of an IAPT service can be effective and cost effective as a standalone intervention.

Strengths and limitations

The trial was large and was executed within IAPT. This increases its validity as this is a real world context where this type of intervention is used and also the population recruited represents the real population that would be using this type of intervention. The length of the intervention also followed IAPT design.

In terms of limitations, the authors did not follow up waitlist controls for ethical reasons. Waitlist controls will overestimate effects as well. In this case, it could be justified if individuals were on a waiting list for IAPT. That was not the study design, though. Participants were eligible to start treatment as usual, so that might have been the comparator that most closely would have mirrored what would be offered to these participants.

The authors list other limitations that I did not feel were likely to have a significant effect on the results.

I would have liked to see comparators such as psychoeducation groups or bibliotherapy rather than waitlist controls, as those might be realistically offered to people waiting for treatment as usual within IAPT.

The main strength of this study was the fact that it was executed within IAPT services with a pragmatic design, conferring it good validity. The main limitation was the use of waitlist controls as opposed to using other low-intensity interventions.

Implications for practice

- This study supports the idea that iCBT can be a cost-effective alternative within stepped-care models

- We are seeing a rising prevalence for depression and anxiety and digital interventions can increase accessibility and efficiency for healthcare systems

- This study done in a real live IAPT service shows that it is possible to integrate digital interventions into existing services without much disruption and with minimal training

- Triage for eligibility can be integrated into current triage systems that exist within IAPT.

iCBT can be a cost-effective alternative within stepped-care models.

Statement of interests

I am CEO and co-founder of a company that develops iCBT applications and also provides guided self-help services using our iCBT programmes as the basis for those interventions.

Links

Primary paper

Richards, D., Enrique, A., Eilert, N. et al. A pragmatic randomized waitlist-controlled effectiveness and cost-effectiveness trial of digital interventions for depression and anxiety. npj Digit. Med.3, 85 (2020).

Other references

Mukuria, C., Brazier, J., Barkham, M., Connell, J., Hardy, G., Hutten, R., Saxon, D., Dent-Brown, K., & Parry, G. (2013). Cost-effectiveness of an Improving Access to Psychological Therapies service. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(3), 220–227.

NICE (2011). Common mental health problems: identification and pathways to care

Photo credits

- Photo by William Hook on Unsplash

- Photo by Alex Radelich on Unsplash

- Photo by Fabian Blank on Unsplash

- Photo by Artem Beliaikin on Unsplash

- Photo by Tugce Gungormezler on Unsplash

- Photo by Štefan Štefančík on Unsplash