It’s well established that depression often first occurs during adolescence. There is quite a lot of research into what can be done to prevent depression, and/or help youngsters who might be experiencing mental distress. The Mental Elf has covered this extensively, with recent blogs on depression prevention programmes, school-based CBT for anxiety and low mood, mindfulness in schools, trajectories of depression in young people, targeting unhelpful repetitive negative thinking and antecedents of depression in young people.

There is a growing body of literature around universal approaches to depression and anxiety prevention in schools, for example this systematic review (more in the links at the end of this blog). This trial adds to that.

This trial, conducted in Australia from 2014 to 2016, looked at whether a web-based gamified intervention based on CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) principles could prevent depressive symptoms in final-year secondary school students around final exams. The researchers’ justification for the trial design was that stressful life events are precursors to depression. Final exams are extremely stressful for final-year students because, in Australia, the marks from these exams translate into entrance scores for post-secondary education admissions. They are even more stressful for academically gifted students from selective schools. Therefore, the researchers reasoned that this would be a good context to test the effectiveness of a universal depression prevention intervention.

Exams are notoriously stressful for final-year secondary school students in Australia.

Methods

The trial was very well designed in terms of the timing of the intervention relative to exams and school graduation:

- Baseline assessments were taken at the beginning of the academic year (February 2015)

- The intervention ran for five weeks and post-intervention assessments were taken the week after

- The six-month follow-up point (August 2015) coincided with the start of the exam period

- Finally, there was a follow-up 18 months after baseline (12 months after the exams, August 2016), at which point participants had graduated from school.

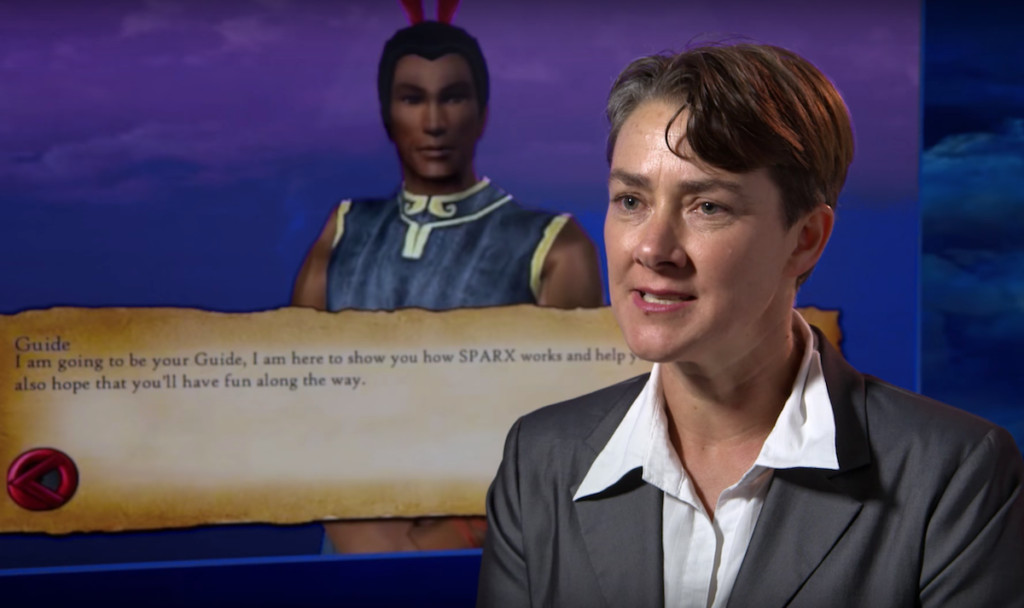

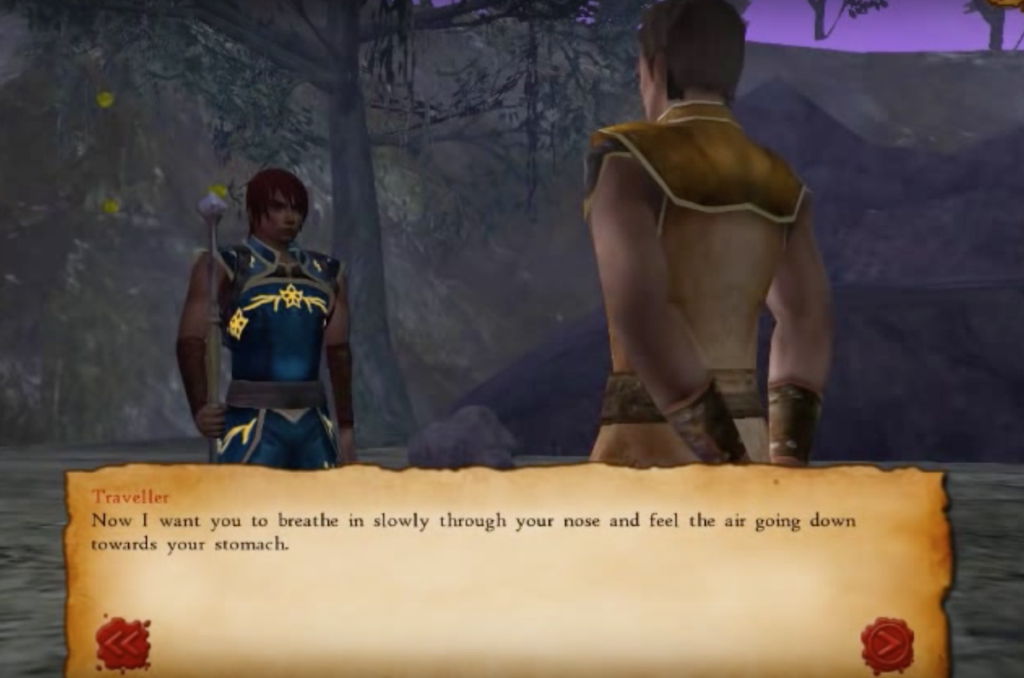

The intervention was a gamified online CBT intervention called SPARX-R, based on another intervention called SPARX, which was designed as a treatment for depression in adolescents who have asked for help with depression. See the SPARX website and this YouTube SPARX trailer for more information about the online CBT game. For this trial, the SPARX game was modified using preventive language and localising it for Australia so it included relevant contact details of local helplines and services.

The control group took part in an intervention that took an equal amount of time, called lifeSTYLE, which had been developed previously as a control intervention for a trial in adults, but was modified in this trial to suit teens.

Researchers chose selective (schools that use an entrance exam) and partially selective schools (schools that offer selective and comprehensive education streams) for conducting the trial, based on prior evidence that the students who attend these schools represent a population that is particularly likely to find final exams very stressful. As this was a universal intervention there were no participant exclusion or inclusion criteria. Randomisation was at school-level (rather than class-level). All students were able to access the interventions but only those who had given consent to participate in research had to complete the research questionnaires and outcome measures.

Eight selective and two partially selective schools took part in the trial. Schools were randomised by a statistician not involved in the implementation of the trial and who was blind to the identity of the schools. All study staff except two trial managers were blinded. Schools were not informed whether their assigned programme was the experimental or the control condition. In terms of blinding, this trial is exemplary.

The researchers tried to get comparable groups at the start of the trial in terms of selective/non-selective stream, gender, country of birth, language spoken at home, age, depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, social phobia symptoms, subjective health, and whether the student lived with both parents together, but ended up with a greater percentage of males, students from selective streams, and students living with both parents together in the intervention group. There were 242 students in the intervention group and 298 in the control group.

Both intervention and control programmes were the same length and both groups completed their assigned programme during scheduled class time. The outcomes were collected online privately.

The primary outcome was the:

Secondary outcomes were anxiety and stress measures. All outcomes were measured using validated instruments:

- SCAS-GAD (Spence Child Anxiety Scale – Generalised Anxiety Disorder)

- SCAS-SA (Spence Child Anxiety Scale – Social Anxiety)

- DSS (Depression Stigma Scale).

Results

The primary outcome was the MDI score at 6 months post-intervention. Usable data was available for this for 140 students in the intervention group and 201 students in the control group. 22 additional students from the intervention group and 2 from the control group completed the outcome measure after the exams, so their data had to be excluded.

The researchers performed a basic intention-to-treat analysis using all available data (from 242 students in the SPARX group and 298 in the lifestyle group respectively). They used a mixed-model repeat measures analysis. This uses all available data and assumes that missing data is missing at random. They also tried to mathematically take into account clustering (the assumption that the scores of students from the same school will be less varied than those of students from different schools) and the variation in baseline variables.

In addition, the researchers conducted analyses of just the “completers” (students who completed 4 or more modules), and analyses of just the students from selective schools. They acknowledge that this method of analysing is more prone to bias.

The intention-to-treat analysis showed that the participants in the intervention group had greater reduction in MDI scores than participants in the control group at post-intervention and 6 months. The effect was not significant at 18 months. All effect sizes were small.

| SPARX-R | lifeSTYLE | |||||||

| Test | Baseline n=242 mean (SE) | Post n=206 | 6m n=140 | 18m n=40 | Baseline n=298 | Post n=200 | 6m n=201 | 18m n=64 |

| MDI | 14.9 (0.9) |

11.9 (0.9) |

13.3 (1.0) |

10.0 (1.1) |

14.0 (0.9) |

14.7 (0.9) |

15.3 (0.9) |

11.0 (1.0) |

| SCAS-GAD | 6.7 (0.4) |

5.9 (0.4) |

6.5 (0.6) |

5.1 (0.5) |

6.8 (0.4) |

6.4 (0.4) |

6.6 (0.4) |

5.7 (0.5) |

| SCAS-SA | 7.2 (0.5) |

6.4 (0.5) |

6.5 (0.5) |

6.1 (0.6) |

7.4 (0.4) |

6.8 (0.5) |

6.6 (0.5) |

6.5 (0.5) |

| DSS | 9.4 (1.0) |

8.9 (1.1) |

8.4 (1.1) |

8.1 (1.1) |

8.8 (1.0) |

8.8 (1.0) |

8.1 (1.0) |

7.8 (1.0) |

142 students completed more than 4 modules of SPARX, whereas 263 students completed more than 4 modules of the control intervention lifeSTYLE. These students were defined as “completers”. The researchers performed analysis on just the completers and found, unsurprisingly, that the intervention was effective for them, and that those who completed fewer modules didn’t show significant intervention effects.

The researchers found no significant effects on any of the secondary outcomes. The researchers point out that academic outcomes didn’t differ between groups.

The researchers say this is the first trial to demonstrate a preventive effect on depressive symptoms prior to a significant and universal stressor in adolescents.

Conclusions

The researchers state that this is the first trial to demonstrate a preventive effect on depression prior to a significant and universal stressor in adolescents.

This was a well-conducted trial that shows promise for preventive mental health. It showed that the SPARX game was effective at reducing depressive symptomatology among the trial population. The intervention is relatively low-cost and doesn’t require trained professionals to implement.

As the trial was conducted primarily in selective schools, among academically gifted students, the researchers urge caution in generalising the results. The students were also, in general, quite well psychologically, with baseline average MDI scores well below the cut-off threshold for mild to moderate depression.

It is also important to mention that the completion rate of the intervention wasn’t great; only 59% of the group completed 4 or more modules of the game. This raises some questions about those who did not complete the intervention and the reasons why they did not complete it. The paper offers some explanation in form of a classic example of what happens when a trial design doesn’t survive contact with real-life conditions. The researchers state that one of the reasons that students in the experimental condition did not complete it, or did not complete as many modules as they could have, was the amount of technical difficulties encountered. Several schools’ IT systems were unable to cope with the number of students accessing the game and/or the research platform at once. The students in the control group, which did not encounter these difficulties, completed more modules of their control intervention.

All that said, it is important to bear in mind that this was a universal intervention that included adolescents with clinical, sub-clinical, and no symptomatology. In a study with this kind of population, you would expect to see a relatively small effect. Nevertheless, a small effect in this context is still important; as Ioana Cristea explains in this Mental Elf blog about web-based guided self-help.

On the whole, this trial adds to the evidence base for universal interventions for preventive mental health in adolescents, as well as the use of digital technology for preventive mental health.

This trial suggests that an online intervention delivered in advance of a stressful experience can help to prevent or minimise depression.

Links

Primary paper

Perry Y, Werner-Seidler A, Calear A, Mackinnon A, King C, Scott J, Merry S, Fleming T, Stasiak K, Christensen H, Batterham PJ. (2017) Preventing Depression in Final Year Secondary Students: School-Based Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res 2017;19(11):e369 DOI: http://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8241

Other references

Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H. (2017) School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, Volume 51, 2017, Pages 30-47, ISSN 0272-7358, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.005.

Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, Freund M, Wolfenden L, Hodder RK, … Wiggers J. (2017) Systematic Review of Universal Resilience-Focused Interventions Targeting Child and Adolescent Mental Health in the School Setting. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(10), 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780

O’Connor CA, Dyson J, Cowdell F, Watson R. (2017) Do universal school-based mental health promotion programmes improve the mental health and emotional wellbeing of young people? A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14078

Cristea I. (2016) Web-based guided self-help can prevent or delay major depression, The Mental Elf. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/depression/web-based-guided-self-help-can-prevent-or-delay-major-depression/

Photo credits

- By Narek75 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

[…] This is an example of a well conducted research trial. It also says something important about the effectiveness of the SPARX programme which delivers CBT in the form of a game. Here is the trailer for it. […]

It may be beyond me, but it claims to be preventative but the intervention included those with clinical symptomatology. Wouldn’t that be a treatment, rather than a prevention. Did they report how well the prevention worked for those with no symptomatology? Thanks.

Thanks for your comment.

In terms of the trial including those with “clinical symptomatology”, I am not sure whether the blog post is a bit unclear on this, so I hope the below can clarify things a bit.

All participants had to complete the MDI (Major Depression Inventory) before the intervention, directly after the intervention, six months after the intervention, and 18 months after the intervention. The MDI has cut-off points of 21 to 25 for mild depression, 26 to 30 for moderate depression, and 31 to 50 for severe depression. Any symptoms that add up to a score of 20 or under would be classed as “subthreshold”, “subclinical”, or “no or doubtful depression”.

The mean baseline score for the MDI at baseline was 14.9 in the SPARX group and 14.4 in the lifeSTYLE group. So, on average, participants had depressive symptoms which were not severe enough to meet clinical criteria for major depressive disorder.

The researchers did measure the prevalence of depression (=how many participants had symptoms that met clinical criteria for major depressive disorder) at post-intervention, 6 months, and 18 months. paper states that “there were no differences between conditions in the prevalence of depression at any time, based on MDI caseness criteria, with caseness of 4.9% (10/206) in SPARX-R and 8.5% (17/200) in lifeSTYLE at post-intervention (P=.17), 11.9% (15/126) and 9.4% (19/202), respectively, at 6 months (P=.46), and 2.4% (1/41) and 4.7% (3/64), respectively, at 18 months (P>.99).”

Note that there is no information here about depression caseness at baseline. All that is reported here is that there was a small number of participants that had symptoms meeting clinical criteria at each measuring point after the intervention.

There is no subgroup analysis of those cases specifically, or of just the participants whose symptoms didn’t meet clinical criteria.

Regarding your query about treatment vs. prevention: The intervention was specifically designed to prevent depression rather than treat it. It’s possible that those who already had symptoms that met clinical criteria were unable to benefit from it and that that is why the number of depression cases didn’t go down over time. But there is no way to know for sure because the paper does not report this, and we don’t know whether the 10 participants from the SPARX group who had high depression scores post-intervention are also among the 15 who had them it at 6 months, and whether the 1 person who had them at 18 months post-intervention belonged to either of those groups.

Please let me know if that answers your query.

[…] obesity (Adab et al, 2018) to improving students’ social skills (DiPerna et al, 2018) and preventing depression (Perry et al, 2017), the role of schools is widely implicated in recent […]