Anxiety and depression are the most common mental health problems worldwide, with more than half a billion people affected and approximately 1 in 5 children and young people. This places a considerable burden on individuals and society (Beddington, Cooper et al. 2008) and much research has focused on finding effective interventions.

In recent years, research in both humans and animals has repeatedly highlighted the important role that gut microbiota (i.e. the microorganisms that live in our digestive system) play in regulating the brain and behaviour, particularly within in the context of mental health and well-being (Mayer 2011, Cryan and Dinan 2012, Foster and McVey Neufeld 2013, and this Mental Elf blog). The gut and the brain are connected via the gut-brain axis, which involves bidirectional communication via neural, endocrine and immune pathways. Our gut microbial composition, which itself alters throughout the lifespan and in response to factors such as stress and lifestyle choices such as diet, has been shown to regulate gene expression and the release of metabolites in the brain (Tillisch, Labus et al. 2013).

Moreover, in adults, atypical variations in microbiome composition have been shown to be related to symptoms of anxiety and depression, but little is known about how the microbiome affects mental health and well-being in the developing individual. This is particularly critical, as animal research has already demonstrated that adolescence is a critical window where microbiota help fine-tune the gut-brain axis (McVey Neufeld, Luczynski et al. 2016) , which could be one factor for the significant increase in mental health problems during this period (Paus, Keshavan et al. 2008).

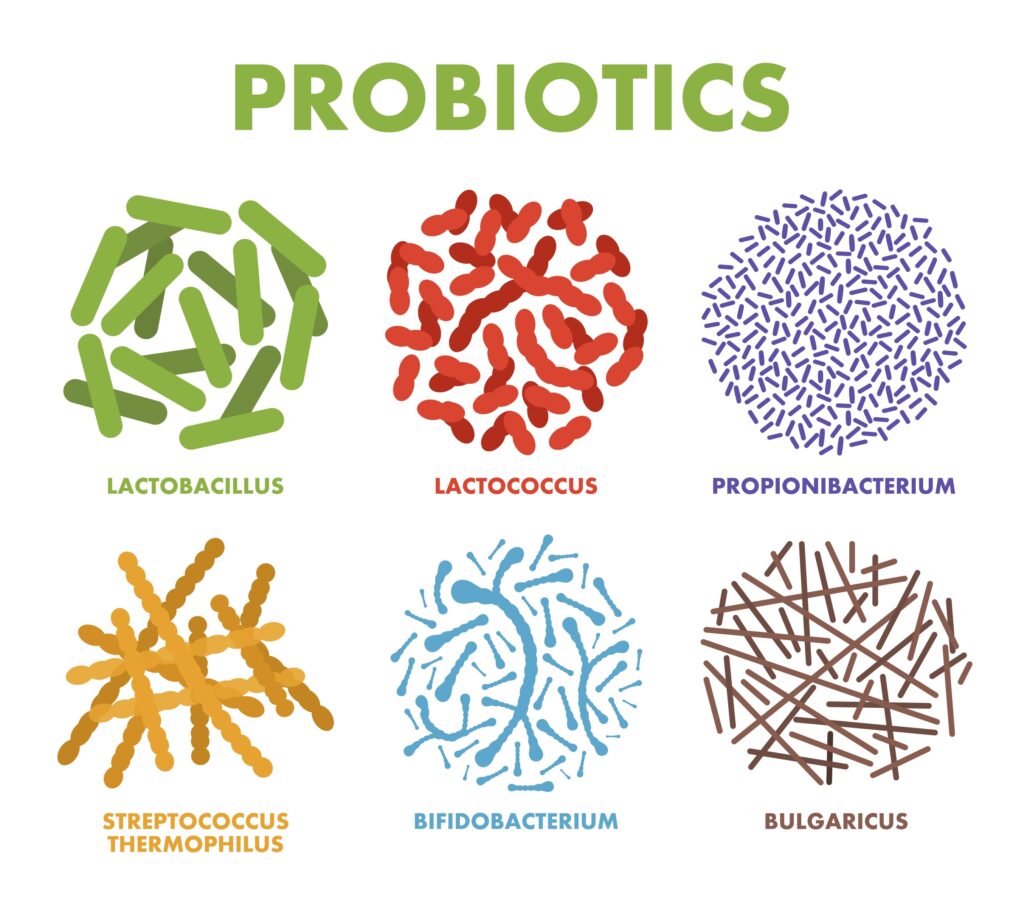

One way of influencing the gut microbiome is via our diet, and research has shown that drastic changes in diet can alter bacterial diversity in mere days (David, Maurice et al. 2014). Therefore, research has focused on how we can use dietary interventions to influence the gut microbiome and the gut-brain axis in order to improve mental health and well-being. For example, dietary interventions using so called psychobiotics (i.e., probiotics and prebiotics) have been shown to reduce anxiety and depression (Sarkar et al., 2016). ‘Probiotics’ are living microorganisms that contribute to the host gut microbial flora, whereas ‘prebiotics’ are non-digestible food (e.g. fibres) which feed the host microbes, i.e. food for beneficial gut bacteria. Probiotics and prebiotics have none of the side effects associated with pharmaceutical interventions (Liu, 2017) and can be easily incorporated into our diet. Another key advantage of psychobiotics is that many cultures have already been eating foods containing psychobiotics for centuries. For instance, anxiolytic strains of lactobacilli have been found in traditional fermented doughs from the Congo and Burkina Faso (Abriouel, Ben Omar et al. 2006), Japanese fermented fish (Komatsuzaki, Shima et al. 2005), dairy and pickles from China and Mongolia (Bao, Song et al. 2016), and eastern European kefir fermented milk (Simova, Beshkova et al. 2002). This means that taking psychobiotics to reduce depression and anxiety could be ripe for a behavioural ‘nudge’, given that these products exist widely in many cultures and therefore potentially present fewer cultural barriers to use.

Therefore, psychobiotics show lots of promise for helping with anxiety and depression, but we need to understand more about for why they work, and for whom and when is the best time to take them.

In this blog, we discuss the findings of a systematic review by Liu and colleagues (2019) on psychobiotic interventions in adults to treat anxiety and/or depression. We then report the findings of our recent Active Ingredient Better Gut Microbiome review, which was commissioned by the Wellcome Trust. For this commission, we conducted a systematic review/meta-analysis of microbiota-targeted (psychobiotics) interventions on anxiety in youth, together with a summary of consultation work of youth with lived experience of anxiety.

Depression and anxiety might respond to dietary interventions that help create healthy gut microbiomes and in turn improve mood and feelings.

Methods

For this systematic review, Liu and colleagues searched Embase, MEDLINE and PsycINFO and searched the references of all prior systematic reviews related to depression and anxiety. To be included, studies had to use either: 1) controlled clinical trial design, 2) human participants, 3) pre- and/or probiotic as only active component of the intervention, 4) depression and/or anxiety measure as outcomes but separately analysed. Study quality was assessed following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions guidelines, which suggest to evaluate the risk of several biases; selection, allocation, performance, detection, attrition and reporting biases.

34 studies met the criteria, and Liu and colleagues extracted data on: 1) sample age group, 2) mean age, 3) sample type, 4) percentage of female participants, 5) form of administered pro-/prebiotics 6) outcome measurement tool, 7) study design, 8) length of intervention. When studies presented with both state and trait anxiety outcomes, the authors chose to select state anxiety as more indicative of immediate treatment effects.

Results

General characteristics of the included studies

The final set included 34 studies: 7 prebiotic and 29 probiotic trials (two studies employed both pro- and prebiotics, and 1 three-arm parallel design with separate conditions for pro- and prebiotics).

Prebiotics

In the 7 prebiotic studies, the prebiotic compounds used were Bimuno-galactooligosaccharide (B-GOS), fructooligosaccharide (FOS), GOS and short-chain FOS (scFOS). Intervention length ranged between 4 hours and 4 weeks. In the meta-analysis, no differences were found between prebiotics and placebo conditions neither for anxiety nor depression results that remained unchanged even after sensitivity analyses.

Probiotics

Of the 29 probiotic trials, two trials focused on Bifidobacterium longum and Bacillus coagulans, and all others on Lactobacilli either alone or in combination with other strains. Intervention length ranged from 8 days to 4 weeks.

Probiotic trials for depression

Probiotic trials for depression were a total of 23 studies with 24 unique effects. Overall, the probiotic group showed lower depression levels after the intervention in comparison with placebo (d=-0.24; 95%CI: -0.36 to -0.12; p<0.01). The heterogeneity level was moderately high (I2=48.2%, p=.01) so that moderator analyses were performed. The effect did not change as a function of mean age, female participants percentage, or duration of intervention. However, treating dichotomously the latter variable revealed significant effects only for treatments longer than 1 month (d=-.28; 95%CI: -.44 to -.13; p<.001). Moderator analyses accounting for the sample type showed a significant and larger effect observed for clinical samples (d=-.45; 95%CI: -.68 to -.23; p<.01) in comparison with community ones. Finally, no significant publication bias was found.

Probiotic trials for anxiety

Probiotic trials for anxiety were a total of 22 studies with 23 unique effects. Overall, the probiotic group presented lower anxiety relative to placebo after the intervention. No significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 =5.0%, p=.39), thus no moderator analyses were performed. Finally, publication bias was modest.

Sensitivities analyses

The authors found that in probiotic trials there were larger effects on depression when Lactobacillus probiotics were combined with other probiotic strains. Yet there was no effect in depression in trials where only lactobacilli were used, and no effect on anxiety.

The systematic review suggests that probiotics represent the intervention of choice over prebiotics, showing effects on both anxiety and depression.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that the:

current evidence base for prebiotics and probiotics in the treatment of internalising disorders appears modest.

Overall, this review reported pooled probiotics effects for both anxiety and depression, although small ones only. It was also found that Lactobacilli alone did not seem to affect anxiety at all, but reduced depression when combined with other probiotic strains.

Future studies should use several probiotics in randomised controlled trials, and assess the effects on depression and anxiety symptoms.

Strengths and limitations

Liu and colleagues have made an important contribution to our understanding of the effects of psychobiotics on depression and anxiety. From this we have learned that, at present, there are too few studies on the effects of prebiotics to draw strong conclusions, therefore more research is required. Yet, we have also learned that probiotics can be effective in treating depression, particularly when the favoured Lactobacilli strain is combined with other probiotic bacteria. This suggests that future studies should use several probiotics in randomised controlled trials looking at effects on depression and anxiety symptoms.

This research addresses several points well. The statistical analysis is sound, and they are able to disentangle and clarify the different trends by examining the effects of moderators. Further, a key strength lies in looking at the differences in multi-probiotic strains compared to the administration of a single strain from which we now know that multi-strains are more effective in reducing depression.

There are also some limitations:

- Liu and colleagues restricted their database search (only 3) and could have searched several others for a more comprehensive review.

- They also treated the variable length of treatment dichotomously although this is not the nature of time.

- Also, although the authors performed moderator analyses, there is a large age range accounted for (e.g., mean age 23 years includes subjects ranging from 18 to 30, thus pooled together late adolescents and young adults resulting in heterogeneity of the sample which crossed the final stage of maturation of the brain and may influence time sensitive effects of pro- and prebiotics on brain physiology).

- Finally, it would be good to see sensitivities analyses based on the risk of bias to see if the high risk had biased the results towards a larger/smaller effect size.

We have learned a lot from this study on which probiotics influence depression and anxiety, yet we need further research on prebiotics and more homogenous samples.

Implications for practice

This review has framed the current research available on pro- and prebiotic administration for improving mental health outcomes. Presently, probiotics look promising for reducing depression symptomology. However, the moderator analyses stress that several factors play a role in determining pro- and prebiotics efficacy highlighting that the formulation of an appropriate research framework is needed. This should be multidisciplinary and follow the example given by the Research Domain Criteria (Inset et al., 2010) to study the microbiota-gut-brain axis in a multi-level way. Also, more attention should be paid to age and the associated developmental stage of research participants as the effects of pre- and probiotic supplementations on brain physiology may be time-sensitive (e.g., have increased efficacy during adolescence) (Neufeld, Luczynski, Oriach, Dinan, & Cryan, 2016).

Using dietary supplements to improve poor mental health is an exciting idea backed up by the results of this study. Pro- and prebiotics are well tolerated by consumers and lack the side effects of other pharmaceutical interventions which means that they might be a good alternative to support health outcomes, although three outstanding questions remain:

- Which specific probiotics and prebiotics are most effective?

- When is the best time for intervention?

- Who benefits most, and for whom are pro- and prebiotics not suitable?

The effectiveness of psychobiotic interventions is best studied in a multidisciplinary research approach.

Your Active Ingredients review “Better Gut Microbiome”

Our research group was interested in how psychobiotics can be used by young people to improve anxiety. Liu and colleague’s (2019) review shows that there is clinical relevance for these specific dietary supplements, so we set out to find whether this is also true for young people, and how using dietary supplements and gut microbiome research is perceived by youth with lived experience of anxiety (in collaboration with the McPin Foundation).

We carried out a systematic review on the effect of psychobiotics on stress and anxiety in young people aged 10-24 years. We used the same methodology as Liu and colleagues and found 14 studies reporting on either anxiety or stress outcomes following pre- and/or probiotic interventions.

We found mixed evidence for the efficacy of probiotics and prebiotics, which was most likely due to the high risk of bias present in all but one of the studies we found. Therefore, we cannot be certain at this stage that probiotics and prebiotics are useful in treating stress and anxiety in young people. However, we suggest that this is because of too much variance in how the research studies available have been carried out (e.g., few of the studies were sufficiently well-designed for us to draw clear conclusions).

Interestingly, our focus group work with young people on the use of dietary supplements for mental wellbeing highlighted a similar theme. Namely, young people asked for scientists to conduct more work into this active ingredient, and that it would be important to investigate the wider context of dietary interventions (e.g., price, accessibility, ease of use and individual circumstances are all important in the young people’s view). Despite this, the idea of dietary supplement for wellbeing was enthusiastically met.

We agree and would suggest to better support mental wellbeing in young people we need to consider individual circumstances and the day-to-day experience of youth. Research studies must also reflect this, and we suggest using multidisciplinary approaches (bringing together scientists from different disciplines such as medicine, microbiology, neuroscience, nutrition science, psychology and psychiatry) in randomised controlled trials to better test the effects of psychobiotics on mental health in young people.

Young people are very interested in using dietary supplements for improving their mental health, but want to be sure of the benefits to them as individuals.

Statement of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Links

Primary papers

Liu, R. T., Walsh, R. F., & Sheehan, A. E. (2019). Prebiotics and probiotics for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 102, 13-23.

Cohen Kadosh, K., Basso, M., Knytl, P., Johnstone, N., Lau, J. Y. F., & Gibson, G. (2020). Active ingredient ‘Better gut microbiome function’. medRxiv, 2020.2011.2009.20228445. doi:10.1101/2020.11.09.20228445

Other references

Kessler, R. C., & Bromet, E. J. (2013). The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annual review of public health, 34, 119-138.

Bandelow, B., & Michaelis, S. (2015). Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 17(3), 327.

Blakemore, S.J., The social brain in adolescence. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2008. 9(4): p. 267-277.

Sarkar, A., Lehto, S. M., Harty, S., Dinan, T. G., Cryan, J. F., & Burnet, P. W. (2016). Psychobiotics and the manipulation of bacteria–gut–brain signals. Trends in neurosciences, 39(11), 763-781

Liu RT, 2017 The microbiome as a novel paradigm in studying stress and mental health. Am. Psychol 72, 655–667. 10.1037/amp0000058 [PubMed: 29016169]

Insel, T., Cuthbert, B., Garvey, M., Heinssen, R., Pine, D. S., Quinn, K., … & Wang, P. (2010). Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders.

Liu B, He Y, Wang M, Liu J, Ju Y, Zhang Y, Liu T, Li L, Li Q, 2018 Efficacy of probiotics on anxiety-A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depress. Anxiety 35, 935–945. 10.1002/da.22811 [PubMed: 29995348]

Neufeld, K. A. M., Luczynski, P., Oriach, C. S., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2016). What’s bugging your teen?—The microbiota and adolescent mental health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 300-312.

Reis DJ, Ilardi SS, Punt SEW, 2018 The anxiolytic effect of probiotics: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical and preclinical literature. PLoS One 13, e0199041 10.1371/journal.pone.0199041 [PubMed: 29924822]

Serretti A, Chiesa A, Calati R, Perna G, Bellodi L, De Ronchi D, 2009 Common genetic, clinical, demographic and psychosocial predictors of response to pharmacotherapy in mood and anxiety disorders. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol 24, 1–18. 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32831db2d7 [PubMed: 19060722.

Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon JI, 2012 Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 486, 222–227. 10.1038/nature11053 [PubMed: 22699611]