I have discussed the use of computerised cognitive behavioural therapy (cCBT) in a previous blog post, looking specifically at adherence to cCBT treatment. As I did then, I have to disclose now that I am an advocate for its use and I run a company that creates cCBT applications. We have been working on adults mainly, but recently we have been reimagining these applications for young people (children and adolescents).

Depression and anxiety are common in youth (Costello et al. 2003) and tend to happen together (Axelson & Birmaher 2001). Both cause many problems for young people and put them at risk of other mental health conditions which can persist into adulthood. However, up to 80% of young people with mental health needs never get any help (Zachrisson et al. 2006). This is in part because treatment is not readily available, but also because kids and their parents fear the stigma linked to mental health problems. Many are uncomfortable talking about these problems and many say that they would prefer self-help (Gulliver et al. 2010).

I thought cCBT might help with some of these issues as it would be readily available, it gives youngsters the possibility to remain anonymous, enables them to pace themselves and it reduces travel costs. In particular with youngsters, the multimedia and interactive appeal of computerised programmes might help engage them better even than adults.

It seems logical that computerised treatments may work for digital natives.

The studies

cCBT is effective in the treatment of depressive (Hedman et al. 2012) and anxiety disorders (Andrews et al. 2010) in adults. I realised I knew far less about how effective cCBT for anxiety and depression in youth is, so before I set out developing anything I wanted to find out what is actually known. I came across two particular studies that I thought would help me with this question.

- The first one is a meta-analysis on all computerised treatments for depression and anxiety in youth (25 years old and younger) published in 2015 by the Royal College of Psychiatrists Expert Advisory Group (Pennant et al, 2015)

- The second one is a meta-analysis also published in 2015 by PLoS ONE, which focuses exclusively on cCBT for anxiety and depression in youth (Ebert et al, 2015)

Instead of looking through one of them and doing my usual appraisal, I felt it would be more useful to look at both. I will refer to them by their first author as the Pennant study and the Ebert study. They overlap in the period of time they look at and they look at many of the same studies.

A meta-analysis is a statistical combination of estimates of a treatment effect derived from two or more similar studies, to give an overall effect estimate. – GET IT Glossary

Methods

Study selection

The Pennant meta-analysis looks at studies published before June 2013 and the Ebert study goes up to December 2013. As may be expected, the basic methodology for both studies is fairly robust, so I have decided to specifically focus on their limitations.

- The Pennant study included 14 studies and the Ebert study 13.

- There were 5 studies identified on the Pennant trial that were not considered in the Ebert study:

- This is because the Ebert study only considered waitlist or placebo controls,

- Whereas the Pennant study included studies with face to face CBT as a control condition.

- There were 4 studies in the Ebert study that were not included in the Pennant study:

- There is no easy way to account for this as these were not studies published after the cut-off for Pennant.

- The Pennant study explicitly rejected studies reporting only outcomes related to potential mechanisms of change like improvements in psychometric training tests, but I could not account for the discrepancy using that criterion.

- The Pennant study considered attention bias modification, cognitive bias modification of interpretation and computerised problem solving therapy in addition to cCBT, but the results were inconclusive and the quality of studies poor.

Quality assessment

- Both studies used the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins et al. 2008). Both studies found risk of bias to be low.

- The Pennant study went beyond that in its quality assessment. It rated the confidence in the results low because of:

- low numbers,

- poor rater blinding and

- quite a lot of therapist intervention in the cCBT groups.

Results

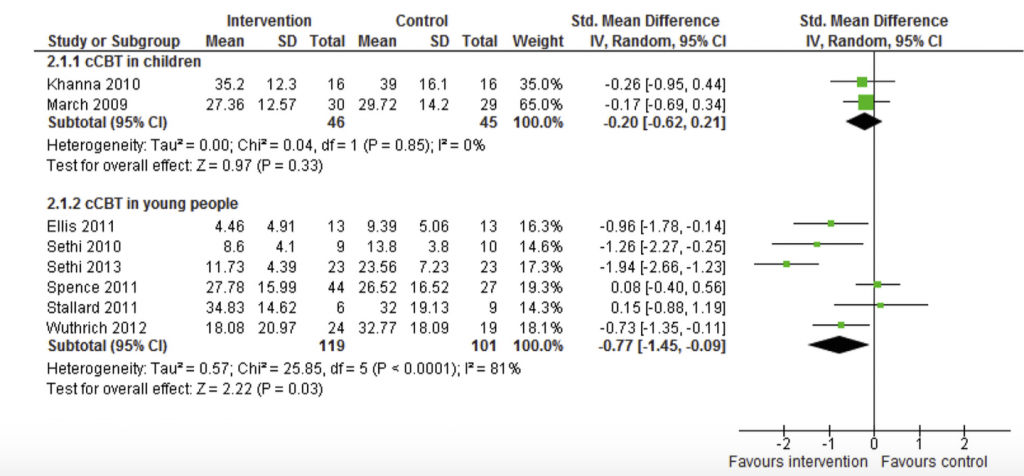

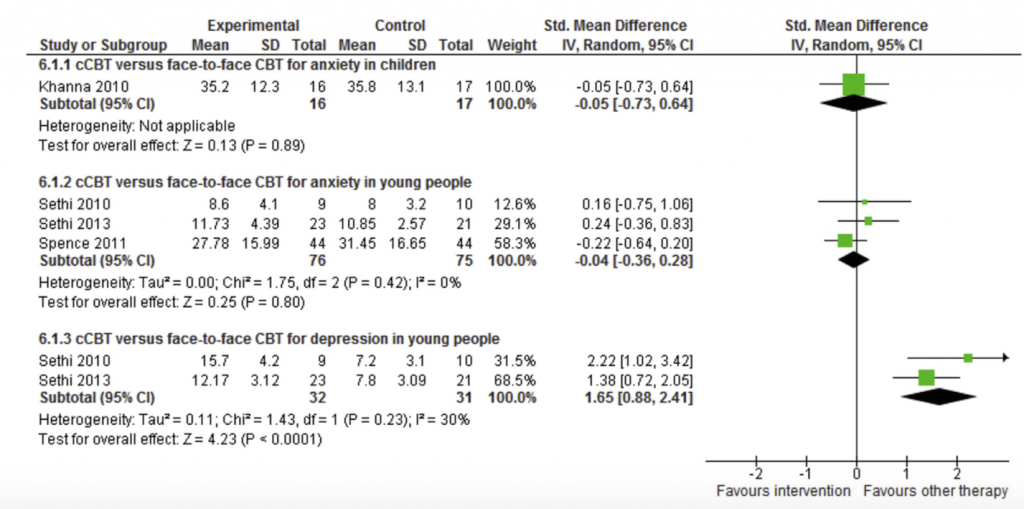

Figure 1 and 2 summarise the results of the Pennant study versus placebo and versus face to face CBT.

The Pennant study concludes that Computerised CBT has potential for treating and preventing anxiety and depression in clinical and general populations of young people. The authors remain unconvinced that there is enough evidence to recommend it in children. They show no advantage of face to face CBT over cCBT except in depression.

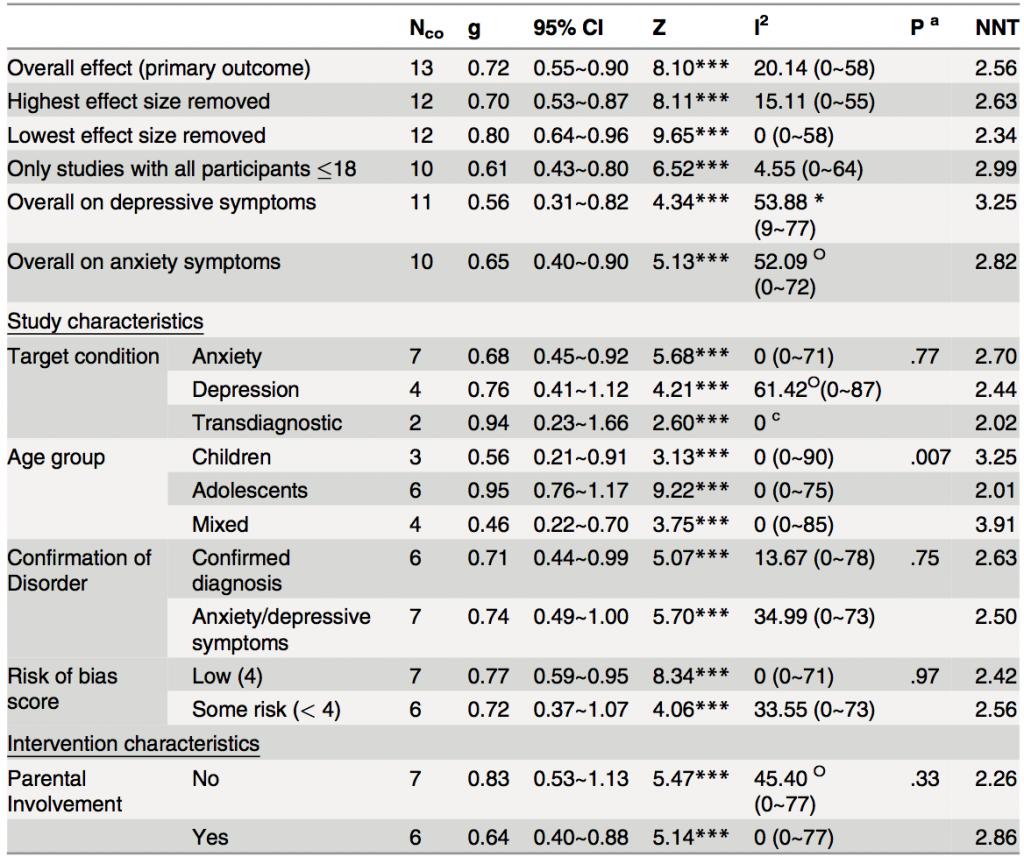

The Ebert study calculates numbers needed to treat as well as effect size. The forest plot shows a significant pooled effect for depression, anxiety and transdiagnostic cCBT interventions. Fig 3 summarises the results given in numbers need to treat.

The numbers needed to treat are generally very low, with higher numbers needed in depression. As seen in the Pennant study, age appears to be a moderating effect with greater efficacy observed in adolescents as compared to children. However the Ebert study concludes that there is a significant effect in children as well, whereas the Pennant study finds the evidence to be insufficient.

Overall, these studies suggest that cCBT may be a promising alternative to face-to-face treatment for anxiety and depressive symptoms in young people.

Conclusion

From reading these two studies I think it is safe to assume that cCBT in young people is an effective way to address both depression and anxiety. The benefits seem to be clearer in adolescents than in children. This is in spite of the fact that many of the studies had low numbers of participants, poor rater blinding and a high level of intervention on the part of therapists.

Reading the studies, my biggest problem was the fact that the interventions were very heterogenous in how they were designed. Length of treatment was variable and even how the treatment was applied differed significantly from study to study. Engagement, which is a perennial problem in cCBT, was not even addressed in the meta-analysis.

I believe there is a good case in general for cCBT and these two meta-analyses seem to confirm that the method also has potential in young people. However, one of the most important things for me is to learn what elements of design in the intervention (length, use of video, use of interactive elements, etc.) are most likely to result in better engagement and greater efficacy. There are no studies looking at these elements and most new studies seem to rehash what has been done before.

In this particular population, the addition of games might be of particular interest. This would not only be to answer the questions of whether games would enhance engagement, but also what type of games might be best used to enhance therapy. Hopefully we will start seeing more papers looking at the effects of different design elements both in youth and older people.

Future research should focus on the specific design elements of the cCBT intervention, to find what increases engagement and efficacy.

Links

Primary papers

Ebert DD, Zarski A-C, Christensen H, Stikkelbroek Y, Cuijpers P, Berking M, et al. Internet and Computer-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety and Depression in Youth: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Outcome Trials. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10(3): e0119895. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0119895

Pennant ME, Loucas CE, Whittington C, Creswell C, Fonagy P, Fuggle P, Kelvin R, Naqvi S, Stockton S, Kendall T. Expert Advisory Group, Computerised therapies for anxiety and depression in children and young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015; 67: 1-18. ISSN 0005-7967 [PubMed abstract]

Other references

Axelson DA, Birmaher B. Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depress Anxiety. 2001; 14(2):67–78. PMID: 11668659 [PubMed abstract]

Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence (PDF). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003; 60(8):837–44. PMID: 12912767

Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review (PDF). BMC Psychiatry. 2010; 10(1):113.

Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012; 12(6):745–64. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.67 PMID: 23252357 [PubMed abstract]

Higgins JM, Altman DG. Assessing Risk of Bias in included studies. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp; 2008:187–241.

Zachrisson HD, Rödje K, Mykletun A. Utilization of health services in relation to mental health problems in adolescents: a population based survey. BMC Public Health. 2006; 6:34. PMID: 16480522

@Mental_Elf Interesting research. :)

Does cCBT hold promise for the treatment of depression and anxiety in youth? http://t.co/nS3MDCS7fk #MentalHealth http://t.co/8a0GdhF4ar

@Mental_Elf all for innovation – cant help wondering if people/ emotion is what youth need- virtual life is harsh with few human comforts

Today @AndrFon on 2 meta-analyses of computerised therapies for anxiety & depression in children & young people http://t.co/PP1uakVQhy #cCBT

Does cCBT hold promise for the treatment of depression and anxiety in youth? https://t.co/o0lCwq6y6f via @sharethis

Is cCBT a promising alternative to face-to-face treatment for anxiety & depressive symptoms in young people? http://t.co/PP1uakVQhy

@Mental_Elf let us know if you or your team would be interested in beta testing our upcoming CBT app for #depression and #anxiety

Mental Elf considers evidence for computerised CBT in youth depression and anxiety https://t.co/MEI8LnJbci

More evidence that Computerized CBT (cCBT) for depression and anxiety works – now also in youth http://t.co/AOFlpVyz1a

What specific elements of Computerised CBT increase efficacy & engagement in young people with depression or anxiety? http://t.co/PP1uakVQhy

Don’t miss: Does cCBT hold promise for the treatment of depression and anxiety in youth? http://t.co/PP1uakVQhy #EBP

“@Mental_Elf: Does cCBT hold promise for treatment of depression & anxiety in youth? http://t.co/pNtH60iqUq #EBP” @UoYMentalHealth

Does cCBT hold promise for the treatment of depression and anxiety in youth? https://t.co/gCzVPSQPuh

@jlperron We can hope, although even with digital natives, the evidence for CCBT isn’t yet convincing http://t.co/R1LuOh7PfT

[…] http://www.nationalelfservice.net/treatment/cbt/does-ccbt-hold-promise-for-the-treatment-of-depressi… […]

[…] access to the relevant treatments for their mental health issues. Fonseca’s article titled “Does cCBT hold promise for the treatment of depression and anxiety in youth?” (2015), discusses how the inaccessibility of treatment and the stigma associated with mental […]