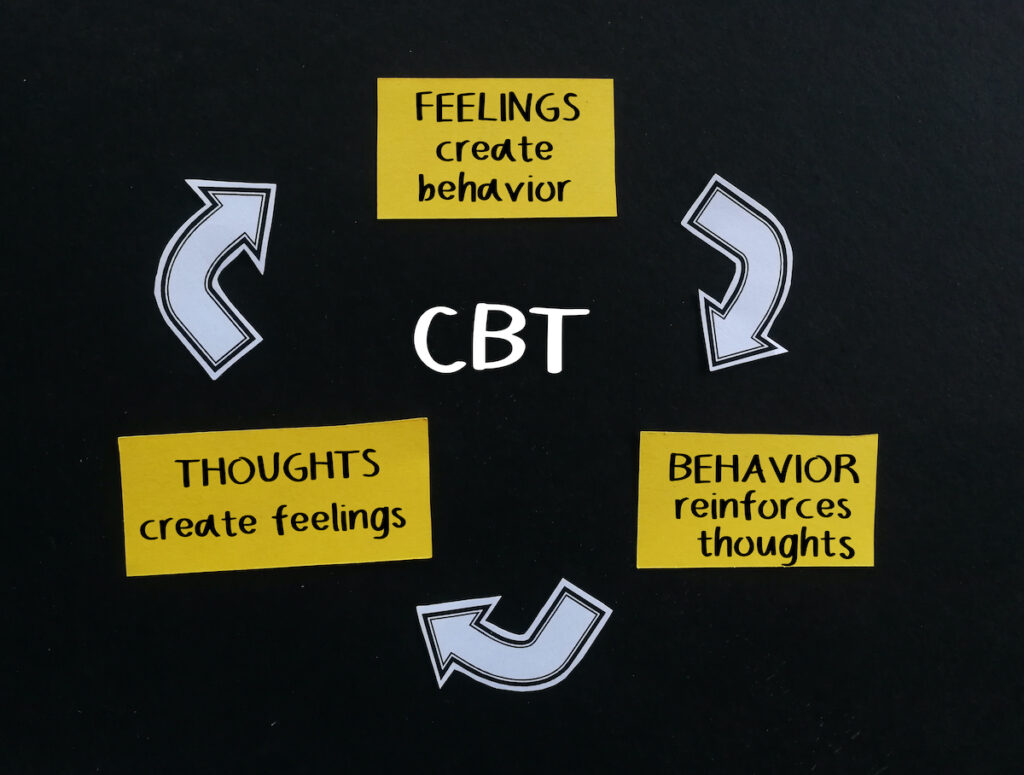

With society rapidly modernising, it is unsurprising that psychological interventions are increasingly being delivered online. Online interventions allow a more creative accessible mode of delivery for patients and flexibility for clinicians to lengthen treatment in contemporary ways. Blended Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (b-CBT) provides online modules in parallel to in-person sessions and has shown success when used for depression (Erbe et al, 2017).

Therapeutic alliance is the professional therapist-patient relationship developed over the course of an intervention by co-operating on agreed-upon tasks and evidencing compatibility through showing trust and respect towards one another.

Little is known about therapists’ experiences of the working alliance (WA). Evidence suggests that the WA may be perceived differently by therapists compared to patients (Titzler et al., 2018.). A recent study (Doukani et al, 2022) aimed to qualitatively investigate therapists’ opinions of achieving a working alliance when delivering a blended CBT intervention for depression.

The working alliance is important for determining the success of psychological interventions.

Methods

The researchers conducted semi-structured interviews and focus groups with a purposively selected sample of IAPT (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies) low-intensity Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (PWPs) (N= 13) recruited across six UK services. PWPs varied in gender, age, years of experience, service location, and the number of participants seen.

Data was audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed by three authors using thematic analysis to ensure consistency with the interpretation.

PWPs reflected on their experiences of delivering and engaging with the b-CBT intervention for depression after offering 11 sessions to clients (6 sessions face-to-face and 5 sessions online). The internet-based component contained online modules and a mobile app where clients could rate their mood daily.

Results

13 PWPs fully participated in the study. 9 PWPs participated in focus groups and 2 PWPs completed individual interviews. 2 PWPs completed interviews and focus groups. The mean sample age was 27 years old (26.6± 2.55). The mean experience level of PWPs was 35 months (35.1± 14.19).

The authors had identified barriers and facilitators to the working alliance (WA) and then linked these together to identify overarching cross-higher order themes.

- The facilitators were the expansion of time, wider toolkit, and tailoring of b-CBT and PWP training and support.

- The barriers included time-intensive, usability problems, inflexible digital programmes and low confidence and practice.

The cross-higher order themes formed through linking the facilitators and barriers together were: 1) experience of time, 2) functionality of the digital programme, 3) flexibility to tailor b-CBT, 4) confidence in delivering b-CBT.

1. Experience of time

PWPs agreed that b-CBT allowed service users to spend more time outside of the clinic engaging with treatment tasks. Therapists felt less pressured to complete content during face-to-face sessions and allowed more time to reflect on the treatment process.

However, therapists struggled to find time to familiarise themselves with the digital programme and oversee patients’ progress online before their face-to-face sessions as the service flow did not align with the treatment needs.

2. Functionality of the digital programme

PWPs agreed that the alliance was strengthened by contacting patients outside of the clinic. The online component covered tasks in greater depth, providing opportunities for patients to reinforce their learning through different means (face-to-face and online).

However, technical issues limited the patients’ ability to engage with the digital component of the treatment. Some issues were fixable (not being able to log in) and some were not (too many notifications from the app). Poor programme usability caused PWPs to struggle to deliver the treatment and maintain a bond where the patient felt motivated and engaged with the process.

3. Flexibility to tailor blended CBT (b-CBT)

PWPs found it helpful that tasks could be adapted, and modules could be targeted to the individual’s needs. However, mandatory modules had to be completed but were not always appropriate for the patient.

Therapists had more flexibility within face-to-face sessions to support any unmet needs which the digital programme failed to address. However, others did not want to diverge from the treatment protocol. The content did not sufficiently address other co-morbid mental health conditions as it only focused on depressive symptoms.

4. Confidence in delivering b-CBT

Few therapists said their confidence to deliver b-CBT was increased by using training resources and technological support. Most felt anxious and lacked confidence and expertise as they felt their roles and responsibilities were not clearly defined in the treatment protocol. This meant that they struggled to deliver the task and felt unable to help patients decide which tasks should be selected to help them with their goals.

Technical issues with the digital usability of the programme and low confidence to deliver blended-CBT in practice hindered the therapeutic working alliance in this group of PWPs and their patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, longer treatment durations and a wider remit of resources helped better engage clients in treatment. Therapists spent more time working on their professional partnership during face-to-face sessions. However, the online component requires minor changes. The programme’s flexibility and receiving support were seen as the foundations of a strong working alliance, yet were absent in this intervention. Usability problems were viewed as fixable or not depending on the exact issue. These issues stopped some patients engaging with tasks and made it harder for the therapist and patient to work together during live sessions. The time and resource intensiveness of the programme and therapists’ lack of confidence hindered the strength of the therapeutic bond, but these were viewed as fixable problems.

Blended CBT interventions for depression (in-person and online) have the potential to improve the working alliance if modified to address issues like usability problems.

Strengths and limitations

This is one of the first studies to explore therapists’ feelings about the working alliance (WA) when delivering and implementing a blended intervention for depression. Clinicians’ expectations of the WA must align with the clients as a strong WA may be compromised due to differences in expectations.

This study has a high risk of bias. Focus groups may have conformity bias, and researcher bias may have affected the way the researcher communicated with participants to evoke a certain response. Data analysis was only done by one researcher who did not state what philosophical/epistemological stance they took. Therefore, we are uncertain about what assumptions they made when analysing the transcripts. Participants may have felt obliged to say positive things about the intervention demonstrating social desirability bias.

There also is a risk of treatment fidelity where the therapists may have been inconsistent with the delivery, as per the treatment protocol. This could have affected the therapists’ views of the WA and consequently the intervention. Future research may want to adopt another methodological design to assess the feasibility and practicality of this intervention in real-life settings.

Little is known in this study about treatment fidelity and the reliability of the treatment administration by PWPs.

Implications for practice

The therapeutic alliance may improve client outcomes of future psychological interventions and better the delivery of these interventions by therapists. Taking into consideration recent evidence of the effectiveness of digital interventions, especially post-pandemic, clinicians should continuously review the applicability of blended interventions for their service users. Mental health problems can occur co-morbidly, so it would be helpful for online interventions to be transdiagnostic.

Online interventions are here to stay, so it’s important for clinicians in public healthcare settings to be up-to-date with current evidence around digital mental health and continue their professional development. To reduce stress and low confidence, ‘digital navigators’ who are devoted to the digital programme could be recruited to resolve technical issues, train therapists, and review patient data.

Therapists should be better supported with the technical issues to allow more time to develop a strong working alliance when treating depression using blended CBT.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Doukani, A., Free, C., Araya, R., Michelson, D., Cerga-Pashoja, A., & Kakuma, R. (2022). Practitioners’ experience of the WA in a blended cognitive-behavioural therapy intervention for depression: qualitative study of barriers and facilitators. British Journal of Psychology, 8(1), 1-9.

Other references

Erbe, D., Psych, D., Eichert, H.C., Riper, H., & Ebert, D.D. (2017). Blending face-to-face and internet-based interventions for the treatment of mentak disorders in adults: systematic review. J Med Internet Res, 19(9), e306.

Titzler, I., Saruhanjan, K., Berking, M., Riper, H., & Ebert, D.D (2018). Barriers and facilitators for the implementation of blended psychotherapy for depression: a qualitative pilot study of therapists’ perspective, 12(1), 150-164.