Prescriptions of antidepressants are at an all-time high in England, with 64.7 million items of antidepressants prescribed in 2016. Despite their popularity, antidepressants don’t work for everyone with major depressive disorder (MDD) and, for those who do see benefits, sometimes more than one type of medication is needed.

For many people with MDD, the most successful treatment is combining multiple psychiatric drugs. There are three main ways of using psychiatric drugs in depression:

- Monotherapy: using 1 antidepressant drug

- Combination treatment: simultaneously using 2+ antidepressant drugs

- Augmentation treatment: simultaneously using an antidepressant with 1+ non-antidepressant drugs (e.g. antipsychotics)

Current treatment guidelines recommend augmenting medication for treatment-resistant MDD. Despite their popularity, there is relatively little research exploring the characteristics of people using these treatment strategies. Dold and colleagues aimed to explore how common augmentation/combination strategies are and the sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of people using these strategies.

Antidepressants don’t work for everyone with depression, but for those who do see benefits, sometimes more than one type of medication is needed.

Methods

This international multi-centre study was conducted by the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression (GSRD). It was cross-sectional, with data collected from 10 academic sites across Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, and Switzerland.

Individuals receiving treatment in these academic centres in 2011-2016 were invited to participate if they met the eligibility criteria:

- Inclusion criteria

- Male and female inpatients and outpatients

- DSM IV-TR diagnosis of MDD

- Receiving ≥1 antidepressant drug for ≥4 weeks during current depressive episode

- Exclusion criteria

- Current primary psychiatric disorder other than MDD

- Substance use disorder (except nicotine or caffeine) in previous 6 months

- Concurrent severe personality disorder

Data was collected from medical records and a clinical interview. Trained psychiatrists used interview schedules and questionnaires to ask about sociodemographic factors, mental health problems, and treatment history. Questionnaires included 2 measures of depressive symptoms: the Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D).

Interviewers estimated a retrospective MADRS score for the onset of people’s current MDD episode based on patient’s recall and their medical records. These scores were then used to calculate change in MADRS score during the current episode (retrospective – present MADRS score).

In their analyses, the authors used treatment strategy as their outcome (monotherapy vs augmentation/combination) as well as the number of psychiatric drugs people were taking. Sociodemographic, clinical and treatment characteristics were examined as exposures in multiple statistical tests (between-group comparisons, logistic regressions, and Spearman’s correlation).

Specifically-trained psychiatrists interviewed the 1,410 patients included in this cross-sectional study.

Results

In total, 2,609 people were screened for this study and 1,410 were included (54%). The authors do not include data on how many of those screened were eligible or how many people were invited to participate and declined.

Notably, most of the sample were:

- Caucasian (96%)

- Female (67%)

- Severely unwell:

- 91% had recurrent depressive episodes

- 35% were inpatients

- 53% were unemployed

- 46% had current suicide risk

- The mean duration of participants’ current depressive episode was 204.74 days (SD 164.64)

- Many had comorbid mental or physical health problems.

Augmentation/combination strategies

The study’s first aim was to establish the prevalence of augmentation/combination strategies. Overall, 60.64% of participants were on these strategies, receiving 2+ psychiatric drugs simultaneously.

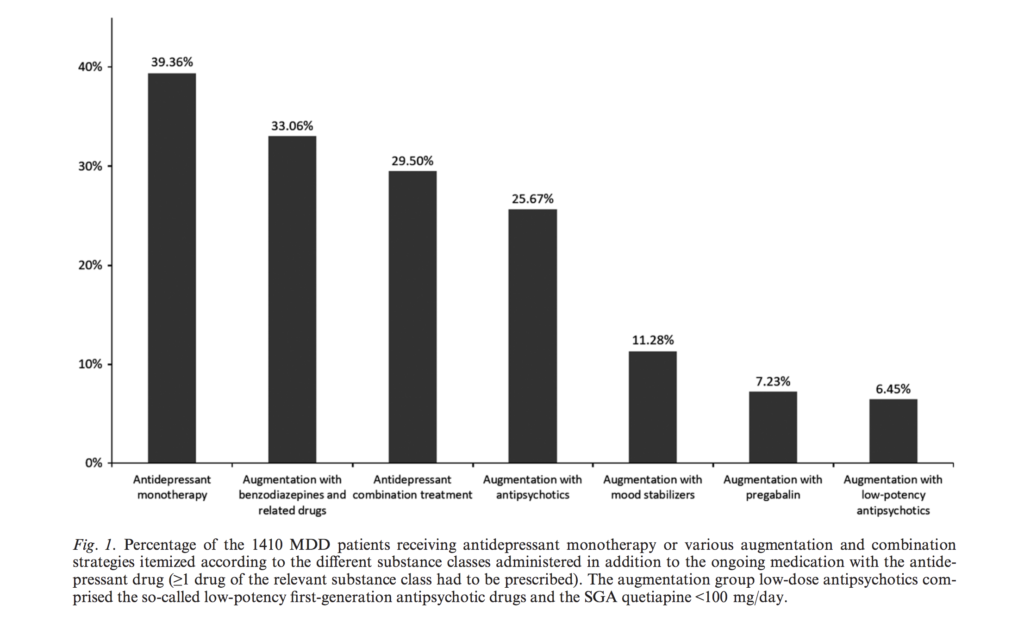

Figure 1 from this paper shows the most common augmentation/combination strategies, broken down by the different drug classes.

On average, participants on augmentation/combination treatment were prescribed 2.95 (SD 0.97) psychiatric drugs simultaneously:

- 25% were taking 2 drugs

- 19% were taking 3 drugs

- 13% were taking 4 drugs

- 4% were taking 5 drugs

- 0.5% were taking 6 or more drugs

On average across the whole sample, people were taking 2.18 psychiatric drugs.

Monotherapy vs augmentation/combination treatment

The study’s remaining aims all involved finding differences between patients receiving monotherapy vs augmentation/combination treatment. Factors associated with augmentation/combination strategies were: male gender, older age, Caucasian descent, higher weight, low educational status, unemployment, psychotic symptoms, melancholic features, atypical features, suicide risk, inpatient treatment, longer overall duration of hospitalisations due to MDD during lifetime, comorbid panic disorder, comorbid agoraphobia, comorbid OCD, comorbid bulimia nervosa, somatic comorbidity in general and especially concurrent hypertension, thyroid dysfunction, diabetes, and heart disease, higher current and retrospective MADRS total scores, treatment resistance, and higher doses of antidepressants.

Despite the differences in MADRS total scores, change in MADRS score during current episode was not associated with treatment strategy. This means there was no evidence for different patterns of changes in depressive symptoms between monotherapy and augmentation/combination treatment.

This study found no evidence that taking more types of medication in combination led to changes in depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

This multi-centre cross-sectional study shows that about 60% of patients with MDD in European tertiary care centres receive augmentation/combination treatment strategies. On average, each individual was simultaneously taking 2.18 psychiatric drugs. Augmentation/combination strategies were more common than in previous surveys, suggesting that using add-on medications for MDD may be increasing in popularity.

As recommended in clinical guidelines, augmentation/combination strategies were more common in severe and treatment-resistant MDD. People receiving additional psychiatric drugs had more severe and complex symptoms, higher risk of suicide, and were more likely to have psychiatric and somatic comorbidities.

This European research suggests that 60% of people with major depression are taking 2 or more psychiatric drugs.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. They had a relatively large sample, recruited from across Europe. Specifically-trained psychiatrists collected in-depth data from participants using clinical interviews. Additionally, the authors performed a number of statistical analyses, replicating their own results.

However, performing multiple comparisons is also a disadvantage of this study. The large number of statistical tests, with many variables, increases the likelihood of false positives (where evidence is found for associations which are due to chance). The authors acknowledge this, stating that it “should be critically considered when interpreting our results”, but have not attempted to correct for multiple comparisons or use fewer tests.

Additionally, this sample was not representative of everyone with MDD. Participants were recruited from tertiary care, so were probably more unwell or had more comorbidities than people in primary care. Also, only 54% of those eligible took part in this study, making the sample less likely to be representative.

The cross-sectional design is also a limitation. The authors did attempt to examine symptom change with the MADRS change score. But, participants had to recall their symptoms at the start of their current episode (over 200 days ago for most people), so this may not be a great measure. The design also means the direction of some associations is not clear. Differences in characteristics such as weight and cardiovascular disease between treatment strategies may be a result of side effects of the drugs themselves, rather than a factor determining which drugs people are prescribed.

Implications

This study demonstrates that, in a severely depressed population, augmentation/combination strategies are being used in difficult-to-treat MDD, as per clinical guidelines. Compared to previous studies, the use of augmentation/combination strategies appears to be increasing. This increase should not be taken as proof of the effectiveness of these strategies but may reflect recent evidence of their efficacy.

Using multiple psychiatric drugs to treat major depression appears to be on the increase, according to this new European study.

Links

Primary paper

Dold M, Bartova L, Mendlewicz J, Souery D, Serretti A, Porcelli S, Zohar J, Montgomery S, Kasper S. (2018) Clinical correlates of augmentation/combination treatment strategies in major depressive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018 Feb 28. doi: 10.1111/acps.12870. [Epub ahead of print]

Other references

Photo credits

- Photo by JOSHUA COLEMAN on Unsplash

- Jamie CC BY 2.0

- Photo by Kyu Lee on Unsplash

- Kiaran Foster CC BY 2.0

- Photo by Martin Sanchez on Unsplash

As someone who has been a participant in a trial following the Star*D protocol for treatment of major recurrent depression, I have to raise the issue of clinical measures vs patient experience. The eventual combination of drugs (fluoxetine augmented by tri-liothyronine ) shifted my depression from severe to moderate. What this actually meant was the difference between me staying in bed and getting up and going to work. The previous iteration of lithium was abandoned early not because of low clinical effect but because it kept my wife awake (dry mouth = I snore loudly) and as a needle-phobic I couldn’t tolerate the weekly blood tests. So my measure of success is different to the clinicians’. Also relevant is the timescale – over the last 5 years of being on T3 without proper review (my GP: ” I’m sorry that’s above my pay grade to look at that”) I have developed osteoporosis and lost an inch in height. So the long term effects and ease of withdrawal also need to be taken into account

[…] resistant depression is to give people more drugs, either anti-depressants or other types of drugs. This piece from the Mental Elf looks at evidence about […]