It’s been a rough few months for people taking antidepressants. We’ve been bombarded with information that insists our medication is ineffective and harmful, that any benefit we gain from taking these pills is simply a placebo effect, and that by accepting a prescription of antidepressants we are joining an ever-growing zombified mass of morons.

From Peter Gøtzsche’s ‘evidence’ that antidepressants don’t just have side-effects but actually kill the people who take them, to the BBC Panorama programme “A Prescription for Murder?” which linked taking antidepressants to violent crime, to Johan Hari’s recent book questioning everything about depression “Lost Connections”, the anti-antidepressants voices have really hit the mainstream.

Of course this is all unsurprising, with around 350 million people worldwide living with clinical depression and NHS prescriptions for antidepressants at an all time high, there is clearly something to be concerned about. Are we medicalising normal human experience, paying too much heed to the pharma-marketing and overprescribing powerful psychotropic medication, or are we seeing increasing levels of illness worldwide that reflect a genuine need for evidence-based interventions (talking therapies, medication and other psychosocial treatments)?

The economic burden of depression in the USA alone has been estimated to be more than US$210 billion. There are lots of evidence-based treatments but because of inadequate resources, antidepressants are used more frequently than psychological interventions. There is considerable debate, both in the scientific literature and in the mainstream media about the efficacy and safety of antidepressants (Ioannidis, 2008), so a major new review in this field is very welcome.

People who take antidepressants have been bombarded by mixed messages about their medication over recent years.

Methods

This network meta-analysis (Cipriani et al, 2018) contains the largest amount of unpublished data to date, and open science fans will be delighted to hear that all the data from the study have been made freely available on Mendeley Data. Overall, 522 double-blind RCTs (1979-2016) of 21 commonly used antidepressants were included, which makes this the largest ever meta-analysis in psychiatry and probably the largest network meta-analysis in medicine in terms of number of double blind RCTs included.

The analysis has a total of 116,477 participants (87,052 people randomly assigned to receive a drug, and 29,425 to receive placebo). The majority of patients had moderate-to-severe depression. This review is an update of a previous meta-analysis (Cipriani et al, 2009), which just included head-to-head comparisons of 12 antidepressants, so whichever way you look at it, this is a big piece of important evidence.

RCTs were excluded if they had patients with bipolar depression, symptoms of psychosis or treatment resistant depression.

The authors searched a comprehensive set of databases, the websites of regulatory agencies, and international registers for published and unpublished double-blind RCTs, from inception to Jan 8, 2016. They identified all double-blind RCTs comparing antidepressants with placebo, or with another antidepressants (head-to-head trials) for the acute treatment (8 weeks) of major depression in adults aged 18 years or more. Importantly, they also contacted pharmaceutical companies, original study authors and regulatory agencies to supplement incomplete reports of the original papers, or provide data for unpublished studies. The value of this comprehensive methodology is borne out when you read that they retrieved unpublished information for over half (52%) of the trials included in the meta-analysis (#AllTrials anyone?). Clearly there’s always more unpublished data out there, but the reviewers should be commended for putting together such a comprehensive data-set.

This substantially bigger data-set has given the reviewers the opportunity to investigate outcomes they couldn’t include in their previous review (Cipriani et al, 2009), such as remission, change in mood symptoms and dropouts due to side-effects, as well as a number of methodological issues, such as sponsorship, dosing schedule, study precision, and novelty effect.

Primary outcomes

- Efficacy (the number of patients who responded to treatment, i.e. who had a reduction in depressive symptoms of 50% or more on a validated rating scale over 8 weeks)

- Acceptability (proportion of patients who withdrew from the study for any reason by week 8).

Unfortunately the reviewers did not have access to individual-level data, so were not able look at the effectiveness or acceptability of antidepressants in relation to age, sex, severity of symptoms, duration of illness or other individual-level characteristics.

There are more people in this study than you can fit in the Nou Camp. It’s quite simply the biggest and most reliable evidence we have to date about the efficacy and safety of antidepressants for adult depression.

Results

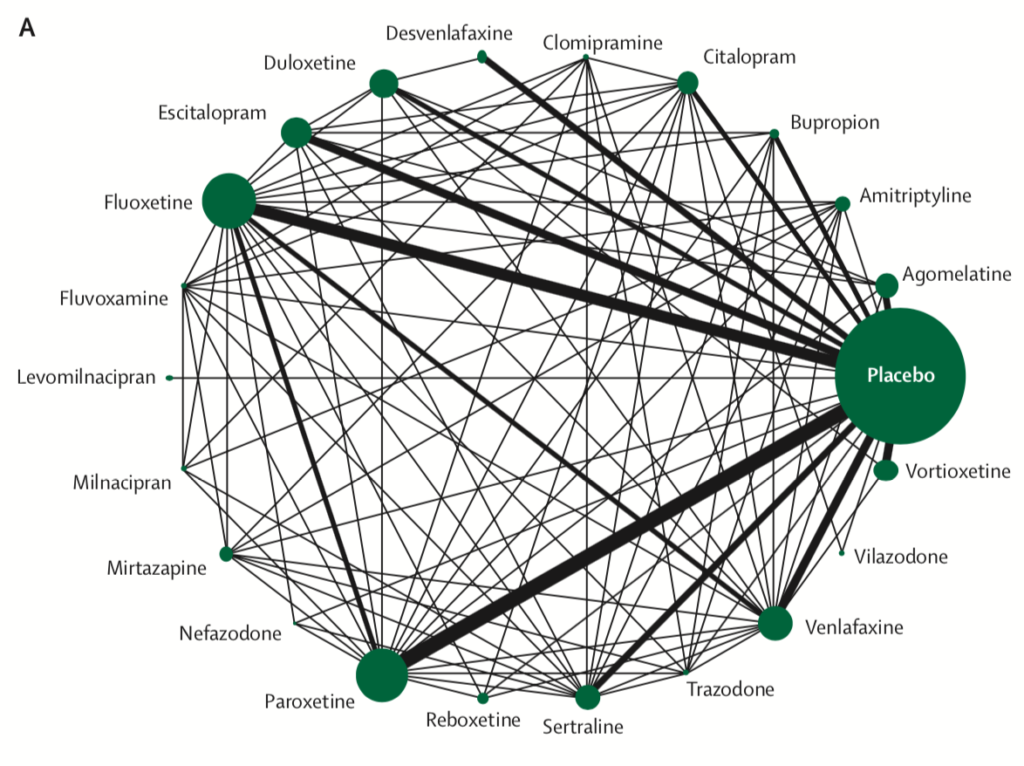

Efficacy

- All 21 antidepressants were more effective than placebo

- The most effective antidepressants were agomelatine, amitriptyline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, paroxetine, venlafaxine and vortioxetine

- The least effective antidepressants were fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine and trazodone.

Network meta-analysis of eligible comparisons for efficacy. Width of the lines is proportional to the number of trials comparing every pair of treatments. Size of every circle is proportional to the number of randomly assigned participants (ie, sample size). View full size.

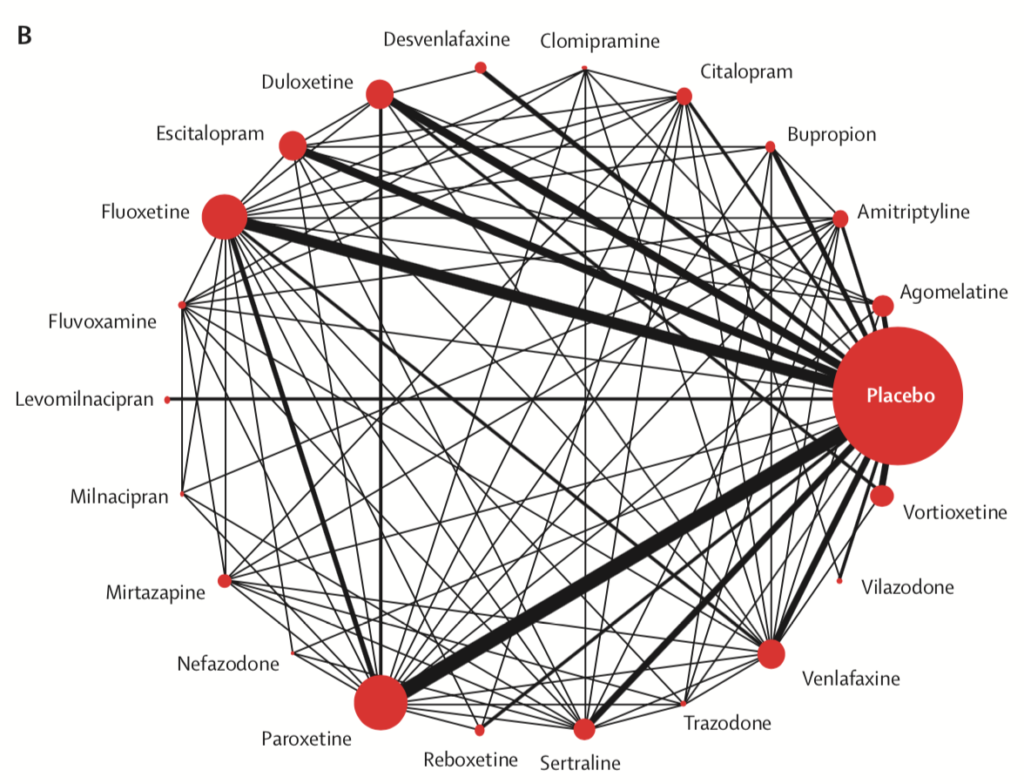

Acceptability

- Only clomipramine was less acceptable than placebo

- The most tolerable antidepressants were agomelatine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline and vortioxetine

- The least tolerable antidepressants were amitriptyline, clomipramine, duloxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine, trazodone and venlafaxine

Network meta-analysis of eligible comparisons for acceptability. Width of the lines is proportional to the number of trials comparing every pair of treatments. Size of every circle is proportional to the number of randomly assigned participants (ie, sample size). View full size.

The included data covers 8-weeks of treatment, so may not necessarily apply to longer term antidepressant use.

The differences in efficacy and acceptability between different antidepressants were smaller when data from placebo-controlled trials were also considered.

Industry funding was not associated with substantial differences in response or dropout rates, but non-industry funded trials were few and many trials did not report or disclose their funding.

Antidepressants tended to show a better efficacy profile when they were novel and used as experimental treatments than when they had become old. This novelty effect might arise where a novel agent is perceived to be more effective and better tolerated; alternatively, selective analyses and outcome reporting bias might be more prominent when a treatment is first launched.

Conclusions

The reviewers concluded:

These results should serve evidence-based practice and inform patients, physicians, guideline developers, and policy makers on the relative merits of the different antidepressants.

Patients and clinicians should make use of this updated review to make shared decisions about their care.

Strengths and limitations

- The design of this network meta-analysis and inclusion of unpublished data is intended to reduce the impact of individual study bias as much as possible

- Of course, the vast majority of included trials (78%) were funded by pharmaceutical companies

- 9% of the included trials were rated as high risk of bias, 73% as moderate and 18% as low

- The quality of many comparisons was assessed as low or very low for amitriptyline, bupropion, and venlafaxine, whereas it was often rated as moderate for agomelatine, escitalopram, and mirtazapine

- Many trials did not report adequate information about randomisation and allocation concealment, which restricts the interpretation of these results

- The lack of individual-level data makes it impossible to investigate issues such as age, sex, symptom severity or duration of illness

- The review did not cover specific adverse events, withdrawal symptoms, or antidepressants used in combination with other non-drug treatments, which is clearly practically useful information for most patients

- The included trials were short (8 weeks) and some antidepressant side effects occur over a prolonged period, so positive results should be interpreted with caution

- This network meta-analysis looks at antidepressants when prescribed as an initial treatment. Given the modest effect sizes, non-response to antidepressants will occur. These results are not relevant to treatment-resistant depression and the reviewers point out that evidence in this group of patients is much more scarce

- The study was funded by the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Implications for practice

The review strikes a nice balance between presenting this strong evidence that antidepressants work for adult depression and accepting the limitations and potential biases in this data. Prescribers should familiarise themselves with the detail in this open access paper and appendix, as it contains a huge amount of useful data for patients, clinicians and guideline developers.

We know from another recent meta-analysis by Cipriani et al (2016) that fluoxetine is probably the only antidepressant that might reduce depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. There are significantly fewer studies in young people so much more uncertainty about the risks and benefits of antidepressant treatment.

The reviewers are optimistic about how future research could also include the individual-patient data missing from this analysis, so-called individual-patient data network meta-analysis:

This analysis will allow the prediction of personalised clinical outcomes, such as early response or specific side-effects, and the estimate of comparative efficacy at multiple timepoints.

Individual-patient data network meta-analyses – the next step in pooling large data sets to offer more personalised and targeted treatment for depression.

So, I’m going to carry on taking my antidepressants, having read this new evidence. I already knew that they worked for me, along with the talking treatment, exercise, diet, mindfulness and music that I’ve been using in combination since I was diagnosed a few years ago.

I hope this evidence offers some reassurance to other people who take medication for their depression. Of course drugs are not the only treatment, but they are a vital part of the range of interventions we have to help people live productive and fulfilling lives.

Links

Primary paper

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. (2018) Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018; published online Feb 21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7.

Other references

Ioannidis JP. (2008) Effectiveness of antidepressants: an evidence myth constructed from a thousand randomized trials?

Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2008; 3: 14.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. (2009) Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatment meta-analysis. Lancet 2009; 373: 746–58.

Cipriani, A et al. (2016) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. The Lancet , Volume 388 , Issue 10047 , 881 – 890.

Photo credits

- Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash

- Carsten Schertzer CC BY 2.0

- Photo by Simon Connellan on Unsplash

I know I’ve definitely noticed a huge difference since going on anti-depressants. Thank you for sharing!

Thank you for this very informative piece.

I think another key limitation not mentioned here is the study’s failure to include active-placebo trials (as far as I can make out). As far as I am aware, it is already well-known that most types of anti-depressants perform better than inactive placebo in the short-term, but also that there is very little difference (if any) between antidepressants and active placebos (i.e. non-psychiatric drugs with similar side-effect profiles). This seems an important caveat before we conclude that we are seeing clinical effects, and not participants (or researchers or MDTs) accurately guessing which arm of the study they are in (e.g. Fisher & Greenberg, 1993).

I appreciate that no study can do everything, but it would be interesting now to compare these comparisons with other psychoactive drugs both prescribed and illicit. I don’t think it is guarantee that an ‘anti-depressant’ would necessarily occupy the top spot for short-term antidepressant effects.

Lastly, if you believe anti-depressants work for you, you find any side-effects tolerable, and feel able to make an informed decision about longer-term harms and benefits, then perhaps you should continue to take these medications regardless of this study?

Interestingly, one of the study authors is John P A Ioannidis who published a famous study “Why Most Published Research Findings are False” http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. Admittedly that was 2005. I know that this study included unpublished research too which is great. But did it find all the unpublished data? In theory 85% of the published findings in the analysis were false. Unless they got hold of the original data from all the published studies as well and reanalysed it? And not all of the unpublished data was found so I wonder if that would have a bearing too. I am not trying to diss the use or usefulness of anti-depressants at all, but the media message is way too simple.

Hi Caroline,

I think your point here is incredibly important. As you say, Ioannidis’ brilliant work has shown us just how poor the vast majority of health research actually is. Couple this with Ben Goldacre’s pioneering #AllTrials campaign, which tells us that half of medical research is unpublished and the picture really is bleak.

However, as you well know, systematic reviewers can only work with the primary research they have, whether it’s published or unpublished. For me, the thing that is so worth highlighting about this Cipriani review is that he and his colleagues did an incredible job at finding a huge amount of unpublished data. They also used the very latest network meta-analysis techniques to minimise potential biases and give the most accurate results they could in their study. Of course there are lots of limitations, but what this analysis gives us is the most accurate picture we’ve ever had about the safety and efficacy of antidepressants for first or second presentations of adult depression. We may well look back in 10 years at this data and scoff at it’s flakiness, but right now it’s the best we’ve got!

The over-simplification of this research in the media was unsurprising. I actually think that overall the reporting was pretty decent. There were a few attempts to present the results graphically which I think were very misleading, but I’ve taken to Twitter to try and right those wrongs.

Keep those comments coming. You’re going to get so many elf points at the end of this month!

Cheers,

André

I still think that however heroic the efforts of the researchers in finding half the unpublished data, this was an academic exercise. Efficacy is so far away from effectiveness, yet covered by the verb “work” in all the media. And as for safety…how can this have been covered even slightly adequately if all studies longer than 8 weeks were not included and adverse events data always under-reported or mis-reported, or both. I had not kept track of the coverage of this study but was wondering how long it would take for Peter Gøtzsche to weigh in….it didn’t take very long! https://www.madinamerica.com/2018/03/rewarding-companies-cheated-most-antidepressant-trials/

[…] of debate about what this research actually means. The Mental Elf has something important to say here. This is very good from […]

To have a real understanding of the safety of these drugs you have to know the phenotype of the metbolising enzymes of each individual, which is totally possible with pharmacogenetics. You also have to know the common food stuffs, herbs and spices which inhibit the CYP450 enzymes and the drugs which also inhibit CYP450… also totally possible. When an adverse reaction happens it is usually put down to the illness and not the drug, the dose increased or drug changed which can and usually does exacerbate the condition being as it is not tapered slowly enough and a patient can spiral out of control on polypharmacy with GP’s and psychiatrists in denile that the drugs caused the problem and that it was their fault.

Perhaps not that clear cut? https://www.madinamerica.com/2018/02/challenging-new-hype-antidepressants/

Michael

[…] Antidepressants can help adults with major depression […]

[…] recent meta-analysis in the Lancet (Cipriani A et al., 2018) concluded that 21 antidepressants, including all commonly […]

[…] for years (and notably a recent blog by chief Elf André Tomlin on Cipriani et al’s analysis of antidepressants had a similar key debate […]

[…] Mental Elf article does have a positive title: “Antidepressants can help adults with major depression” and an overall positive assessment, but there were some clear limitations noted as well. First, […]

[…] Twitter: @Mental_Elf Website: The National Elf Service and the Mental Elf Blog: André’s blogpost on the Lancet paper […]

[…] meta-analysis by Cipriani et al (2018) presented the best available evidence to date about the efficacy and safety of antidepressants for adult depression. This review concluded that “all antidepressants were more efficacious than placebo in adults […]