Antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are frontline treatment for depression. Prescriptions of antidepressants have more than doubled in the last decade according to figures from NHS Digital.

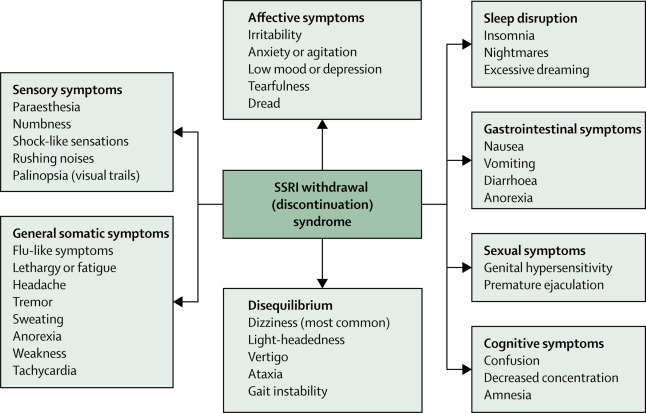

When coming off of antidepressants (cessation), individuals can experience withdrawal syndrome. This can highly resemble the symptoms of depression, such as low mood and feeling suicidal. This can make people feel that they are relapsing and become depressed again, which can in turn lead to them starting back on their antidepressants when actually they are not needed.

Previous (controversial) research has found that when given a scale to describe the withdrawal effect severity, nearly half of people choose the most extreme option (Davies & Read, 2018). Further, the discontinuation period (the 14 days after cessation) has found to be associated with a 60% increase in suicide attempts (Valuck & Orton, 2009). Moreover, patients are hesitant to stop antidepressant use due to the aversive nature of the withdrawal syndrome.

The distress caused and risk of long-term unnecessary medication use make it important to minimise withdrawal symptoms. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) therefore recommends that antidepressants should be tapered (reduced), for between two to four weeks before complete cessation, rather than abrupt discontinuation. However, studies have shown that tapering for up to two weeks has no benefits compared with abrupt discontinuation (Tint, Haddad & Andersont, 2008), suggesting perhaps longer tapering regimens are required to best reduce distressing withdrawal symptoms from antidepressants.

Methods

A recent ‘personal view‘ published in The Lancet Psychiatry by Dr Mark Horowitz and Prof David Taylor reports on their work examining the PET imaging data of serotonin transporter occupancy by SSRIs, which found that “hyperbolically reducing doses of SSRIs reduces their effect on serotonin transporter inhibition in a linear manner”. This blog is a summary of that paper.

Neurobiology and management of withdrawal

During withdrawal antidepressant medication is reduced so there is less serotonin in the brain. The brain is used to having a higher amount of serotonin and so this change disturbs the equilibrium in the brain. Slowly reducing SSRIs means the brain will have more time to adapt to this slower amount of serotonin and this will reduce the severity of symptoms. Therefore, a pause is recommended between reducing the dose of medication.

What happens in the brain during SSRI withdrawal?

SSRIs work by stopping serotonin transporters bringing serotonin back into the nerve cell. This leaves more serotonin to be transferred around the brain.

When SSRIs are stopped there is no additional serotonin and so some of the benefits of having extra serotonin stops. The deficiency of serotonin and other brain chemicals can also play a role in withdrawal. There is less serotonin interacting with the receptor that is involved in motor sickness, and this may play a role in the nausea and dizziness that is a symptom of withdrawal syndrome. There is also less serotonin involved in the system of the body controlling heart rate and digestion, which may explain some other symptoms of withdrawal syndrome.

Does everyone experience SSRI withdrawal?

Withdrawal symptoms are more common when SSRIs are given in high doses or for long periods of time. Not everyone will have SSRI withdrawal. There are differences in patients (like our genetics) that determine withdrawal effects. If patients start taking SSRIs again after discontinuing them, their symptoms generally stop within 24 hours, but they may not need the medication anymore. The key phrase to remember for clinicians when tapering SSRIs is “go slow as you go low!” Most importantly, tapering should be an individualised process as there may be differences in withdrawal symptoms in different patients.

The brain acts uniquely and withdrawal symptoms are different for everyone.

Implications for practice

The authors highlight the problems with current guidelines for coming off antidepressants and offer an alternative solution, based on the biology of the drugs themselves and how they work on the brain. Reducing the dose of medication more slowly at the end of withdrawal and over a longer period appears to be a safer option. This could prevent many people who have recovered unnecessarily staying on antidepressants due to the effects of the short sharp withdrawal methods suggested by current guidance. Having reached a level of recovery where medication no longer feels necessary, it may be empowering for people to successfully maintain wellness, so guidance that can ensure withdrawal does not “send people backwards” is critical.

Any improvements to the extremely unpleasant antidepressant withdrawal symptoms for people experiencing depression are welcomed. However, in context this guidance has been suggested without testing the method. Future research should put their suggestions to the test, through comparing the experiences of service-users withdrawing from antidepressants using the authors method against the experiences of those withdrawing from antidepressants using current guidelines. Future psychology research is also needed to design talking therapies that can help people stay well after coming off antidepressants and to develop their own strategies to cope with symptoms if they return.

This evidence supports the view of many patients who have struggled to withdraw from antidepressants: “go slow as you go low!”

Strengths and limitations

The approach taken by Horowitz and Taylor (2019) is applicable to clinical practice because it provides suggestions for clinical guidance that have the wellbeing of service-users at their heart. The suggested model is plausible based on the scientific evidence provided and can help guide clinical practice for the withdrawal of different psychiatric medications that are frequently used. The suggested clinical approach provides a closer doctor and service-user relationship during the withdrawal period, which constitutes a more personalised approach.

However, the medication that the article deals with can have different (withdrawal) effects and do not all follow the same neurobiology, but the authors of the article do not provide different guidance for different types of SSRIs. Moreover, it might be challenging and not feasible to change current clinical guidance before doing a larger trial has been conducted; identifying the exact mechanisms and approaches that might improve the patient’s withdrawal experience.

Lastly, many patients have a long waiting time to reduce their medication, and the long time periods involved in tapering the medication might be frustrating.

Overall, this approach is very interesting for future clinical guidance, but more research should be conducted to explore the underlying mechanisms and feasibility for clinical practice.

Countless patients report struggling to withdraw from antidepressants, so this evidence provides hope for many.

Contributors

Thanks to the UCL Mental Health MSc students who wrote this blog: Melissa Kabadayi (@melkabadayi), Huynh Quynh Tran Nguyen (@JenNg1901), Shathana Navaratnam (@ShathanaNav), Frederike Katharina Lemmel (@FrederikeLemmel), Emily Carratu (@EmilyMentalHlth), Baihan Wang (@wang_baihan), Annamaria Balogh (@annamaribalogh4), Natasha Lyons, Winnie Tsang (@Winniee_Tsang), Rayanne John-Baptiste Bastien (@jbbrayanne), and Siu Long Lee (@michaellee1523).

Conflicts of interest

None.

UCL MSc in Mental Health Studies

This blog has been written by a group of students on the Clinical Mental Health Sciences MSc at University College London. A full list of blogs by UCL MSc students from can be found here, and you can follow the Mental Health Studies MSc team on Twitter.

We regularly publish blogs written by individual students or groups of students studying at universities that subscribe to the National Elf Service. Contact us if you’d like to find out more about how this could work for your university.

Links

Primary paper

Horowitz MA, Taylor D. (2019) Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. The Lancet Psychiatry.

Other references

Davies J, Read J. (2018) A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: Are guidelines evidence-based? (PDF) Addictive Behaviors. 2018 Sep 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.027

Tint, A., Haddad, P. M., & Anderson, I. M. (2008). The effect of rate of antidepressant tapering on the incidence of discontinuation symptoms: a randomised study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 22, 330-332.

Valuck, R. J., Orton, H. D., & Libby, A. M. (2009). Antidepressant discontinuation and risk of suicide attempt: a retrospective, nested case-control study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70, 1069.

Photo credits

- Photo by Paweł Czerwiński on Unsplash

- Photo by Ron Smith on Unsplash

Many thanks for this interesting blog. We notice that it references a critique of our recent systematic review of antidepressant withdrawal. Interested readers can read our response to this critique here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306460319300929

Thanks

“The deficiency of serotonin and other brain chemicals can also play a role in withdrawal.”

Indeed, though I do not know to which extent it is supported by science or not. Best stuff I could find on severe withdrawal symptoms (brain zaps):

https://psychology.stackexchange.com/questions/17361/how-do-brain-zaps-occur

“It proposes an explanation related to norepinephrine. Also, it claims that brain shivers or brain zaps are related to Lhermitte’s phenomenon.”

Hello, students at UCL MSc in Mental Health Studies! Thank you for this article.

I fear the serotonin disruption you cite for being the cause of SSRI withdrawal is not the central factor.

It’s true that there is a biochemical change throughout the nervous system when an artificial prop (the drug) is withdrawn. But SSRIs have systemic effects to which the entire body has adapted, creating a homeostasis dependent on the drug.

Withdrawal symptoms arise because the body has not had opportunity to adjust to a new drug-free homeostasis. (Plus, downregulation of receptors in the serotonin system hampers its regulatory functioning, disinhibiting the sympathetic nervous system.)

The disruption at SERT receptors creates what’s been described as a domino effect throughout the autonomic nervous system.

That is why gradual tapering is advisable — to allow the nervous system and body time to find a new homeostasis, to stabilize. In part, this may mean recovery of normal SERT functioning.

As other non-serotonergic drugs, such as benzodiazepines and supplemental hormones cause withdrawal symptoms very similar to those from SSRIs, it’s probably more accurate to visualize drug withdrawal syndromes as autonomic or nervous system dysfunction and symptom fluctuations (oh, they do fluctuate) as the body’s attempts to re-establish homeostasis.

Skaehill, P., Welch, E.B., 1997. Clinical Reviews: SSRI Withdrawal Syndrome. Consultant Pharmacist 12, 1112–1118.

Black, K., Shea, C., Dursun, S., Kutcher, S., 2000. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Psychiatry Neurosci 25, 255–261.

Haddad, P.M., 2001. Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndromes. Drug Safety 24, 183–197.

Harvey, B.H., McEwen, B.S., Stein, D.J., 2003. Neurobiology of antidepressant withdrawal: implications for the longitudinal outcome of depression. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 1105–1117.

Reeves, R.R., Mack, J.E., Beddingfield, J.J., 2003. Shock-like sensations during venlafaxine withdrawal. Pharmacotherapy 23, 678–681.

Hochberg, Z., Pacak, K., Chrousos, G.P., 2003. Endocrine Withdrawal Syndromes. Endocrine Reviews 24, 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2001-0014

Moncrieff, J., Cohen, D., 2005. Rethinking Models of Psychotropic Drug Action. Psychother Psychosom 74, 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1159/000083999

West, C.H.K., Ritchie, J.C., Boss-Williams, K.A., Weiss, J.M., 2009. Antidepressant drugs with differing pharmacological actions decrease activity of locus coeruleus neurons. Int. J. Neuropsychopharm. 12, 627. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145708009474

Chouinard, G., Chouinard, V.-A., 2015. New Classification of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Withdrawal. Psychother Psychosom 84, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371865

“Withdrawal symptoms arise because the body has not had opportunity to adjust to a new drug-free homeostasis. (Plus, downregulation of receptors in the serotonin system hampers its regulatory functioning, disinhibiting the sympathetic nervous system.)”

You listed quite a lot of references. What is the article you listed that would the most support your claim? (Sorry, haven’t got the time to go through all of them).

(Also saw, you listed Joana Moncrieff as a reference. Man! You’re fearless! Guilt by association is so easily enforced these days…)

I’m sorry, if you don’t trust my summation, you’ll have to do your own work. This is a shamefully neglected field where the dots have not been connected.

Harvey, 2003 contains the neurobiology.

That paper by Moncrieff is very interesting, you should put your assumptions aside and give it a read.

Both the Harvey article and the Moncrieff article are behind paywalls… This unfortunately does not help discussion of this shamefully neglected topic.

I have no assumptions concerning Moncrieff. I just stated that others have shunned her and made her life difficult, which I believe is both objective and shameful. The irony wasn’t explicit enough?

But back to the paywall issue: any psychiatrist that has ever published an article behind a paywall and accused a patient of being antiscience is… a ****.

J Moncrieff treats people as unique human beings, not labelled specimens. I should know. She was the only psychiatrist I had who gave me the truth without preaching but with genuine concern. It’s helped me find out for myself and I miss her, having relocated. But I have experienced many side effects, withdrew me from Lithium (asked for by me due to many dispiriting side-effects and planned beforehand) and I’m so grateful her guidance woke me up. She’s genuine, I can honestly say and truly concerned. There should be more funding for university MH research but of course we know who suppresses any decent evidence-based research and promote only the huge money-making industries.

Hi Authors,

I am an Admin in a large Closed Facebook Group that helps people to taper safely from Venlafaxine. The withdrawal symptoms this drug causes can be horrific and terrifying for people to experience, especially where it has been used for non psychiatric, off-label treatment.

Every day I see people struggling to stop taking it who have either been tapered far too quickly using the standard available formulations of the medication by a doctor or psychiatrist or worse still are switched to another med in a haphazard way causing huge issues of combined withdrawal and side effects from the new medication. I can only assume that these practitioners have had some success in using this approach or have simply misdiagnosed those who suffer withdrawal symptoms with a relapse diagnosis. Either way, many of these casualties of this approach end up in our group (we have over 5,000 members). Most are able to reinstate and stabilise before starting a slow taper off the medication (by slow I mean 10% of the previous dose with a 30 day hold between each reduction – or longer if withdrawal symptoms are prolonged). Many are successful and go on to lead a medication free life. Some find it too difficult and suffer greatly before accepting their fate and staying on the meds, even though they don’t need them. Its is almost always the case that, as per Horowitz & Taylors paper, that the lower doses are the most difficult. It is sad and very worrying to witness. Papers like this are a real breath of fresh air to me and a massive step in the right direction to enabling practitioners to be able to correctly advise patients on a safe way to withdraw from all forms of psychiatric medication.

Thank you for your article.

Cheers

Ed

What is the name of your Facebook group? I would like to apply, i’m in my lower doses step, and it’s difficult.

People who’ve experienced severe withdrawal reactions from SSRI’s are more likely to report them, although it provides reassurance for people changing medications

when the withdrawal effects are outlined, they are easier to cope with. Depression is bad enough without distress caused by discontinuation reactions. I am a pharmacist myself, and when I shared my experience with my colleagues and Co workers, for them, it was like ‘Whoa, I didn’t know it could be like that’ It humanises the experience when someone we know has been through it!