The benefits and risks of antidepressants continue to be hotly debated, both in the scientific literature and in the media.

An adverse effect that has been frequently discussed in the past year has been withdrawal symptoms, experienced when stopping antidepressants.

Recognition of these symptoms in the scientific literature is not new; they have been recognised since the early use of tricyclic antidepressants, though there has been debate around their prevalence, severity, and how quickly they resolve.

A recent review, commissioned by the All Party Parliamentary Group for Prescribed Drug Dependence, has addressed a lot of these questions. James Davies and John Read have examined the literature on prevalence of withdrawal symptoms, and severity. This was heavily featured in the media, with statements made such as Antidepressant withdrawal ‘hits millions’ (BBC) and Now doctors MUST wake-up to the dangers of patients hooked on depression pills (Daily Mail).

Media coverage of the paper by Davies and Read was emotive and damning in terms of the potential dangers of antidepressant medication.

Methods

The authors state this is a systematic review, with evidence compiled according to the standard PRISMA guidelines. They used a systematic search of the literature, using Medical Subject Headings to identify relevant papers.

Results

- They identified studies of incidence of withdrawal symptoms, from randomised controlled trials, naturalistic studies and surveys

- Pooling data together, they found an estimated incidence of 56%. In other words, more than half of people who take antidepressants experience withdrawal

- They excluded studies they considered outliers, in terms of reported withdrawal symptoms

- They then used survey data to estimate the degree of severity of withdrawal symptoms

- They excluded randomised controlled trials and naturalistic studies from this analysis, as they felt they were biased, because they were short-term in nature, funded by the pharmaceutical industry, or the authors had significant conflicts of interest.

Antidepressants have entered popular culture and are one of the most divisive drugs in use today.

Conclusions

The reviewers concluded that:

- Over half of people taking antidepressants experience withdrawal symptoms

- The severity of these symptoms is severe in over half of cases.

Strengths

- A strength of the current study is the attempt to synthesise what is a very heterogeneous set of data, from a number of sources

- The questions they address are highly relevant, given the number of people being offered antidepressant medication and have been relatively neglected in high quality studies.

Limitations

However, there are a number of limitations which reduce the utility of this review:

Literature search

The reviewers claim to have conducted a “systematic search” of the literature, looking for relevant studies to include in their review. This consisted of a MeSH search (no freetext searching) of MEDLINE, plus searches of PsychInfo and Google Scholar, as well as some citation searching. Any information scientist worth their salt would suggest other databases that are likely to yield further relevant research (e.g. Embase and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials). It’s highly likely that this “systematic” review does not include all of the published research in the field, and there’s no evidence that the reviewers did anything to look for unpublished research.

Inclusion criteria

There is no evidence that the systematic review inclusion criteria was registered in advance (pre-registration is designed to prevent changes to methodology once researchers have had a look at the data). From the paper it is not clear if factors such as length of follow-up, length of antidepressant exposure, or drug company funding were defined as reasons for exclusion before undertaking the search and data extraction.

The authors describe exclusion of “outlier” studies which report withdrawal incidence at 11-12% because they assessed “only 9 withdrawal symptoms”, but this outcome measure is not totally at odds with some of the papers they do include. They also exclude a number of studies, summarised by Baldwin and colleagues (Baldwin, 2007), which report withdrawal in the range 6.9% (escitalopram) to 32.7% (paroxetine). Had these studies been included in the analysis, estimates of 11-12% would no longer constitute outliers.

Assessment of study quality

Review articles are notoriously difficult to interpret, and this led to the setting of defined criteria for reviews, which have been called “systematic reviews.” This requires the authors to evaluate study quality, based on attempts to control for issues such as selection bias (samples that are not representative of the population of people we wish to examine), or blinding (whether the participant or the observer knows they are receiving the intervention or not). This is part of the PRISMA checklist, subsumed under the heading, “risk of bias”. This review does not attempt a traditional assessment of bias in the studies they include. These measures enable study quality to be examined, as lower quality studies will invariably produce biased results.

Though the authors make a point of identifying studies funded by drug companies, and where there are potential conflicts of interest related to pharmaceutical companies, they do not assign measures of study quality across studies, and ignore a number of potential biases, such as selection bias.

The title says this is a “systematic review”. In fact, the methodology is far from systematic.

Conflict of interest

Whilst identifying conflicts of interest related to drug companies, ideological or intellectual conflicts of interest are not discussed. As Ioannidis (2016) and others have stated, meta-analyses have become a tool for academics with vested interests which might go beyond those tangible conflicts of interest traditionally defined by journals.

Outcome measures

In addressing the first question-incidence/prevalence of withdrawal symptoms, they consider the measure, change in withdrawal symptoms (DESS) as a definitive measure of withdrawal. All measures have weaknesses, and in three of the studies they present, they omit mention that symptoms identified with DESS are also present in those continuing to take antidepressants (Rosenbaum et al., 1998; Zajecka et al., 1998; Montgomery et al., 2005). In the Zajecka randomised, double-blind study it is worth noting that the incidence of withdrawal symptoms as measured by the scale is higher in those continuing to take antidepressants (76%), compared to those stopping (67%). It is also worth noting comments made in a paper cited by the authors on the DESS (Hindmarch et al., 2000), “defining a “discontinuation syndrome” as an increase of four or more symptoms…may lead to an overestimation of symptoms.” In fact many of the included studies have an even less stringent cut-off to define “withdrawal”. This is not mentioned at all in the Read and Davies article and therefore gives a particularly misleading account of the Zajecka et al. paper.

Furthermore, withdrawal symptoms themselves are not homogeneous; they vary amongst medications and individuals, and no effort is made to unpick this complexity.

Withdrawal symptoms are not homogeneous; they vary amongst medications and individuals.

Non-representative surveys to measure incidence/prevalence

Using survey data has strengths and weaknesses. A strength is the large numbers of people that fill out online surveys. However, a major concern is whether they are representative of the population of interest (i.e., all people prescribed antidepressants). A standard methodology for online surveys is to assess the completion rate, i.e., those who were offered the survey, and those who completed it (Fincham, 2008). But this is not possible with the internet methodology used in all of the surveys included in this review. A potential bias from online surveys is that they will be filled out by a specific group of people (this is seen frequently with polling surveys). Anyone conversant with UK politics will have seen this phenomena over the last few years.

This does not mean that the views of people who complete online surveys are not relevant (they are) and they provide important information about the qualitative nature of withdrawal symptoms in some individuals. However, they cannot provide a valid estimate of the frequency of withdrawal symptoms in people who stop taking antidepressants. Many journals will not publish surveys if it is impossible to gauge the response rate or response representativeness (Cooke et al., 2000).

When addressing the issue of severity of withdrawal symptoms, the authors only consider survey data. The reason given, is that a lot of the randomised trials and naturalistic studies are short-term, or at risk of potential bias owing to conflicts of interest. However, if they are using these studies for the quantification of withdrawal effects, and the data is valid for that purpose, it is baffling why it would not be valid for reporting severity; scrutiny of these studies commonly shows lower severity compared to survey reports. It would have been legitimate, for example to report withdrawal severity from included studies, and then stratify for type of study.

The survey data used in this review may not be representative of all people prescribed antidepressants. People may be more likely to participate in online surveys if they have a negative experience of withdrawal.

Data extraction and presentation of results

There are mistakes in their reporting of a number of studies included in the review:

- In the Montgomery study, the incidence of withdrawal symptoms following escitalopram treatment is presented as 27%, when it is 16%.

- There are 97 people in the Bogetto study, rather than the 95 they report.

- There are 8 patients prescribed paroxetine in the Tint et al., study, rather than 9.

- The Hindmarch and colleagues paper was published in 2000, rather than 2017.

- The total number experiencing withdrawal in the study by Sir and colleagues is 83 rather than 110.

Whilst each of these errors is minor, it does not point to rigorous quality checking by the authors, reviewers or journal editorial staff. Also, where there are errors in reporting the incidence of withdrawal symptoms they are in the direction of symptoms being more frequent; thereby favouring the authors’ view.

Mixing study designs

It is questionable how the authors can justify combining data from randomised controlled trials and naturalistic studies, conducted under study conditions, with survey data. All methodologies have their strengths and weaknesses, though combining data from different methodologies is unconventional, and rarely seen in peer-reviewed literature.

In the presentation of the results of the review, there is no measure of how consistent results were between individual studies. We have tried to address this below.

Combining data from randomised controlled trials, naturalistic studies and survey data is unorthodox and hard to justify.

Combining data from different types of antidepressants

Another potential limitation is the combining of antidepressants with different pharmacokinetic properties, i.e., different ways of being metabolised by the body. For example, fluoxetine has a half-life of 4-6 days after chronic use (active metabolite half-life 4-16 days) compared to paroxetine (approximately 21 hours) and venlafaxine (approximately 5 hours). There is fairly strong evidence to suggest that medications with longer half-lives will be associated with less withdrawal effects, so it is puzzling that the results are presented for all antidepressants combined.

Related to this is the lack of any discussion about the pharmacology of antidepressants and mechanisms for withdrawal, which would have been helpful in explaining the results. Particularly, if a large minority of patients are experiencing symptoms for longer than 3 years (as described in Davies et al 2018) the mechanism for this needs to be understood.

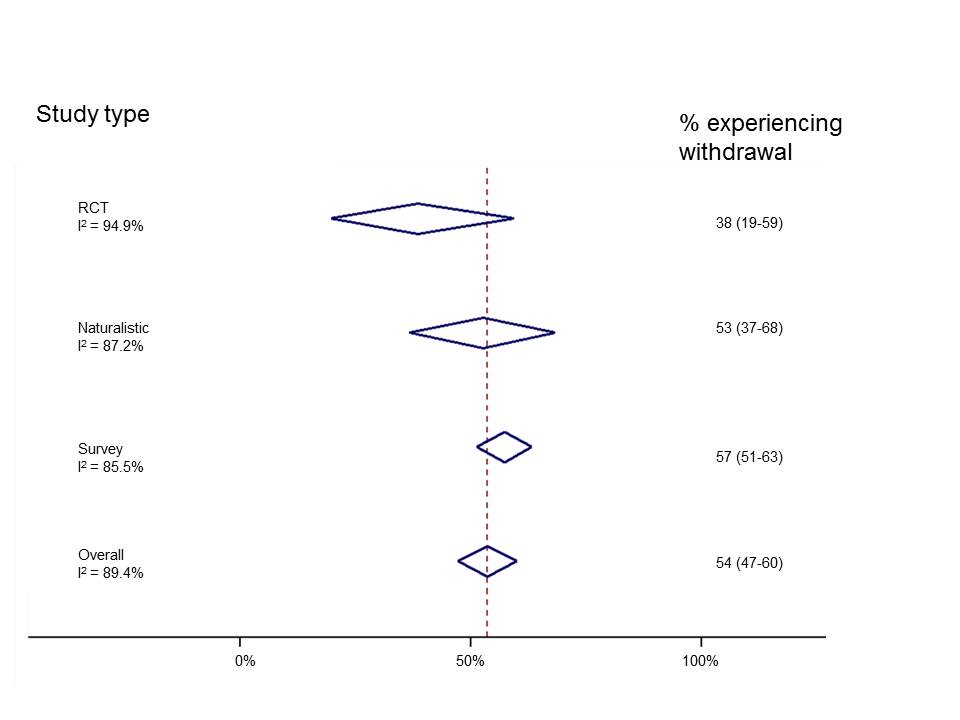

Reanalysis

Given the limitations discussed we urge caution in the interpretation of the incidence/prevalence and severity rates presented. However, we reanalysed only the studies included by Davies and Read in their assessment of incidence (whilst incorporating the corrections we note above) to highlight a number of important points. We organised studies by study type and found that reports of withdrawal events were highest in surveys and lowest in RCTs. Also, we can see (from the measure called I2) that results of individual studies are highly inconstant (I2 can range from 0%-100% and NICE classes I2 of more than 75% “very serious heterogeneity” and would downgrade the meta-analysis for this because there is no precise estimate of withdrawal occurrence). This suggests that combining study designs does not make statistical sense.

Results from individual studies are so mixed that it is unlikely to be meaningful to combine them. Click here to view larger figure.

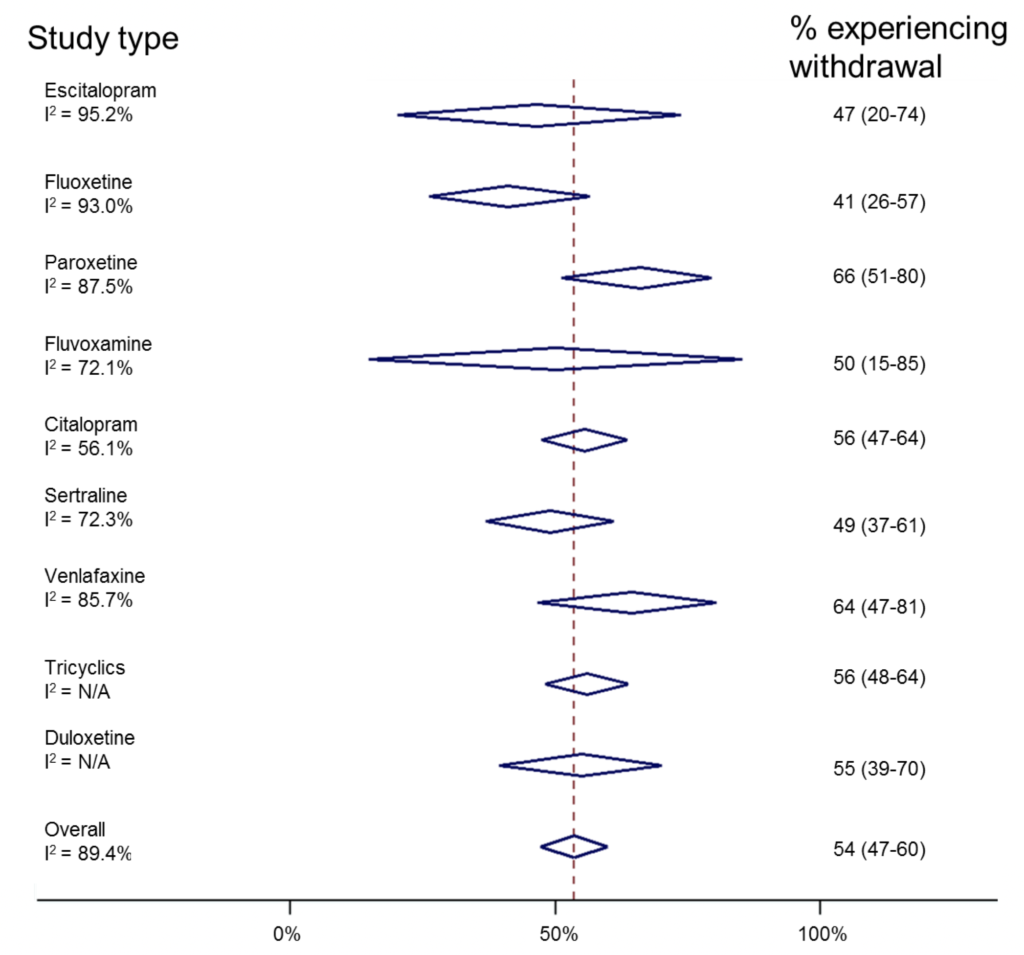

We can do something similar, but this time sorting by antidepressant (though combining studies across different study designs).

Risk of antidepressant withdrawal is likely to be related to its half-life. (N/A=too few studies to calculate I2). Click here to view larger figure.

Similarly, this shows huge inconsistencies between individual studies. However, it suggests that paroxetine and venlafaxine are associated with withdrawal most commonly, and fluoxetine least commonly. This reflects experience in clinical practice and is useful information “hidden” in this review. Ideally, one would look at drug effects in different study designs, though there are insufficient numbers of studies to do this reliably.

Implications for practice

The headlines that followed the release of this review were very clear. They stated that half of people taking antidepressants would experience withdrawal symptoms, and that most people reporting withdrawal symptoms class them as severe.

Looking carefully at the review, it does not accurately portray the data.

Whilst withdrawal effects are high for certain drugs (paroxetine, venlafaxine), when stopped abruptly, this happens very rarely in clinical practice and guidelines are in placed to address this. Furthermore, if people do experience withdrawal symptoms, there are treatments available, such as cross-titrating to a drug with a longer half-life, less likely to cause withdrawal, such as fluoxetine, followed by tapered withdrawal.

The issue of time course of withdrawal is not addressed in the review, but will merit careful analysis of the trial and study evidence, as well as that reported in surveys, where the length of follow-up may well be longer.

In conclusion, this is a very topical review, and the authors no doubt have the very best of intentions in communicating their analysis of data. However, the non-systematic way in which the review is written, with errors in data extraction and interpretation make it difficult to accept the findings with any confidence. It reflects negatively on the whole of the field of psychiatry that there is not better, clearer evidence from high quality studies on the incidence, severity and duration of any symptoms related to antidepressant cessation.

Several of the claims made by Davies and Read about antidepressant withdrawal are unfounded. We have carefully and systematically appraised this review and we conclude that it does not accurately portray the data.

Conflicts of interest

Joseph Hayes is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospital and UCL, and the Wellcome Trust. He has never received drug company funding. He is a Consultant Psychiatrist.

Sameer Jauhar is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, and a SIM Fellowship from the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh. He has never received drug company funding. He is a Consultant Psychiatrist.

Links

Primary paper

Davies J, Read J. (2018) A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: Are guidelines evidence-based? (PDF) Addictive Behaviors. 2018 Sep 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.027

Other references

Baldwin DS, Montgomery SA, Nil R, Lader M. Discontinuation symptoms in depression and anxiety disorders. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007 Feb 1;10(1):73-84.

Cook C, Heath F, Thompson RL. A meta-analysis of response rates in web-or internet-based surveys. Educational and psychological measurement. 2000 Dec;60(6):821-36.

Mayor S. (2016) Five minutes with… John Ioannidis. BMJ

Davies, J et al. (2018) A survey of Antidepressant Withdrawal Reactions and their Management in Primary Care. Report from the All Party Parliamentary Group for Prescribed Drug Dependence.

Fincham, J. E. (2008) Response Rates and Responsiveness for Surveys, Standards, and the Journal. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(2).

Montgomery, S. A. et al. (2005) ‘A 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of escitalopram for the prevention of generalized social anxiety disorder’, The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(10), pp. 1270–1278.

Rosenbaum, J. F. et al. (1998) ‘Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a randomized clinical trial’, Biological Psychiatry, 44(2), pp. 77–87.

Zajecka, J. et al. (1998) ‘Safety of Abrupt Discontinuation of Fluoxetine: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study’, Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(3), p. 193.

de Vrieze J. (2018) Meta-analyses were supposed to end scientific debates. Often, they only cause more controversy. Science, 18 Sep 2018.

Photo credits

- Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

- Gerald Leonard CC BY 2.0

- Photo by Steve Johnson on Unsplash

- Photo by David Pisnoy on Unsplash

- Photo by imgix on Unsplash

To be completely fair, the paroxetine leaflet does state that 3 in 10 will experience problems. That might be 5 out of 10, its still way to high a number for a phenomenon that actually we don’t understand, particularly after long exposure, or have much appreciation of how damaging it is.

The next question is, are patients informed and tapered appropriately. My only experience is for a near maximum dose of an off-label, short half-life drug tapered over 3 weeks – that does not sound like “a number of weeks” or “several weeks”, or “longer than 4 weeks for shorter half life” (NICE).

My understanding is that the last 25% dose reduction would remove a 75% blockade of seratonin reuptake at a stroke – not very sensible.

The two psychiatrist authors state that this new research showing antidepressant withdrawal has been underestimated ‘was heavily featured in the media’ where it received ’emotive and damning’ coverage.

So will they now ask their NIHR & IoPPN colleague Dr Carmine Pariante MRCPsych to publicly retract his ‘finally puts to bed’ media hyping of the February 2018 Cipriani et al antidepressant meta-analysis? After my complaints he has not repeated such statements, but they remain widely on record worldwide in BBC and other mainstream media outputs: https://drnmblog.wordpress.com/2018/04/11/letter-to-the-maudsley-hospitals-chief-executive/

Dr Hayes and Dr Jauhar put ‘ideological or intellectual conflicts of interest are not discussed’ in bold, without citing any authority or evidence as to how such conflicts are to be discussed.

Dr Jauhar has used ‘ideology’ as a crude smear before: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-bulletin/article/ideology-over-evidence/2C152155CFAECC6CF5215F19E5D6A015

I suggest that if neither Dr Hayes nor Dr Jauhar are prepared to say what they mean about ‘ideology’ and an ‘intellectual conflict of interest’ then they reduce their own credibility.

It would be quite in order to say that both James Davies and John Read are non-psychiatrists and academics who arguably have a range of vested interests in undermining both physical treatments and psychiatric diagnosis itself.

John Read has recently made a false statement in relation to Dr David Baldwin, the author of one of the papers that the current authors say should have been included in the Davies and Read review: https://drnmblog.wordpress.com/2018/09/28/john-read-is-not-fit-to-represent-the-bps-on-the-prescribed-drug-dependence-withdrawal-review/

Dr Hayes and Dr Jauhar should have stuck to their reasonable points 1. Surveys have some validity, but it is difficult to precisely extend their findings to estimates of prevalence across whole populations 2. Psychiatry should have done this kind of survey research long ago, and not left it to non-psychiatrists

I have been taking the SNRI venlafaxine for 10 years. My first attempt at withdrawal – following the rapid taper advice from my “expert” psychiatrist – led to an 8 week hospital admission. This was entirely due to horrendous withdrawal (which nearly killed me), and was NOT a relapse of depression, despite being misdiagnosed as such. I am now tapering much more slowly – I intend to take 3+years to get off this awful drug. Even at this slow pace I am going through a living hell, as are many of the members of my venlafaxine withdrawal support group. I was given no warning of this when the drug was prescribed to me and my psychiatrist admitted recently – in writing – that he was unaware of any withdrawal issues associated with venlafaxine – despite prescribing it widely. If psychiatrists expects the public to trust them, they need to start to listen. Whatever the exact number of people suffering with antidepressant withdrawal, the evidence shows that these medications are of no benefit, and in fact lead to poorer outcomes, in the long term. We all deserve to be supported and treated humanely in our battles to get off them. I agree with Dr Peter Breggin – venlafaxine is a neurotoxin. It is poisonous and should be taken off the market immediately. Any psychiatrist who disagrees with me should try taking it for a year, then come off using their own advised tapering schedule. Perhaps then they will finally start to come to terms with the devastation they are causing through the prescription of poisons like venlafaxine.

study authors respond here http://cepuk.org/2018/10/18/3406/ .

their suggestion of having the above peer-reviewed seems sensible?

[…] This article explains the science behind claims in the media about withdrawal symptoms for antidepressants. This is a controversial and sensitive area where it is important to get the science right. The contention of this article is that a paper which received the media coverage got the science wrong. […]

My response can be read here, it is called:

Room under the umbrella: https://holeousia.com/2018/10/22/room-under-the-umbrella/

Kind wishes

Dr Peter J Gordon

GMC number 3468861

Dear Dr. Joseph Hayes and Dr. Sameer Jauhar:

Your blog above is advertised above as “NO BIAS, NO MISINFORMATION, NO SPIN.” Accordingly, the following

questions are even more appropriate to ask of you, especially given your own above admitted conflicts of interest which include working as a “Consultant Psychiatrist” and your own above broadened scrutiny of conflicts of interest to include “ideological or intellectual conflicts of interest” which “are not discussed” which could be charged against any author with a true ideological or intellectual interest in just seeking lifesaving truth no matter what the personal cost:

Question 1: As Dr. Neil MacFarlane appropriately comments above, what specifically and exactly do you mean by stating “ideological or intellectual conflicts of interest are not discussed” (and also in answering please apply the same standard to your own above critique)?

Question 2: Have you applied the same degree of critical scrutiny and rigor (as you have to the above article) on the

research used to justify the current UK and USA antidepressant-use standards of care (including any differences between UK and USA standards) including the research used to justify and validate the nosology used in such standards of care-justifying research, and if you have indeed done this, where are the results of such a “NO BIAS, NO MISINFORMATION, NO SPIN” critique?

Question 3: In your “No Bias” critique answer for Question #2 above, and in your own professional practice of psychiatry in general [especially given the lack of biological markers to prove material brain function abnormalities in psychiatric diagnoses which lead to antidepressant prescribing, as well as, the known brain function abnormalities (including chemical imbalances) that antidepressants iatrogenically cause (e.g., please read the twelve best-in-class references in my links below)] how have you scientifically controlled for the expected huge confounding variable of human soul function as discussed in my epistemological axioms presented in my 5/2/18 letter to the editor of the British Medical Journal and my 8/16/18 Medicaid.gov public comment available for free at the following two URL addresses in the context of two real-life current events U.S. public health policy examples? Note, I ask this because we cannot scientifically rule out an obvious expected interface between human soul function and material brain function which, as a result of research design, is abnormally affected only in those research subjects receiving the psychotropic drug with, therefore, expected possible significant iatrogenic soul-function-brain-function-interface abnormalities causing possibly primarily clinically significant soul function abnormalities which are not being detected because soul function is not being scientifically measured and therefore which may be significantly contributing to the mounting findings of huge under-appreciated iatrogenic effects (including significant morbidity and mortality and disability) from antidepressants and other psychotropic drugs as reported in the twelve best-in-class expert witness references cited in the following links:

https://www.bmj.com/content/356/bmj.j1058/rr-1

https://www.bmj.com/content/356/bmj.j1058/rr-1

https://public.medicaid.gov/connect.ti/public.comments/showUserAnswers?qid=1897507&voteid=352593&nextURL=%2Fconnect%2Eti%2Fpublic%2Ecomments%2FquestionnaireVotes%3Fqid%3D1897507%26sort%3Drespondent%5F%5FcommonName%26dir%3Dasc%26startrow%3D1%26search%3D

https://www.bmj.com/content/356/bmj.j1058/rr-1

https://public.medicaid.gov/connect.ti/public.comments/showUserAnswers?qid=1897507&voteid=352593&nextURL=%2Fconnect%2Eti%2Fpublic%2Ecomments%2FquestionnaireVotes%3Fqid%3D1897507%26sort%3Drespondent%5F%5FcommonName%26dir%3Dasc%26startrow%3D1%26search%3D

Sincerely and In Biblical Love for Both of You and All Psychiatrists Everywhere,

Thomas Steven Roth, MBA, MD

Christian Minister for Biblical Medical Ethics,

and therefore,

Religious and Scientific Refugee from the Clinical Practice of Psychiatric Standards of Care

P.O. Box 24211

Louisville, KY 40224

October 26, 2018

[…] Conselho da Psiquiatria Baseada em Evidências (CEP): “Agradecemos a Hayes e Jauhar por postarem blogs a respeito da nossa recente revisão sistemática sobre a retirada de antidepressivos, mantendo […]

James Davies and John Read have published a response to this blog on the CEPUK website: http://cepuk.org/2018/11/05/antidepressant-withdrawal-review-authors-respond-mental-elf-critique/

Playing by the rules of science?

We thank Dr Davies and Professor Read for their response to our blog, where we outlined what we considered to be significant methodological and errors in interpretation in their systematic review of antidepressant withdrawal.

We believe these errors are still apparent, and are surprised that the authors do not acknowledge basic flaws in conducting this review. Given their response, readers may perceive our concerns as “nit-picking” over minor points. In fact it is the totality of the misrepresentations of the data that concern us.

The rules of conducting a valid systematic review are clearly set out, and unfortunately the authors of this review appear to be oblivious of these.

Our main concerns about this review in general relate to:

1. It is not valid to invert the traditional hierarchy of evidence;

• Randomised controlled trials are the only way of clarifying effects which are attributable to SSRIs and other antidepressants (these are devalued or excluded)

• To ascertain an incidence estimate the total population at risk need to be sampled from (this is not the case with the surveys included)

These errors are magnified in the estimates of severity and duration

2. It is highly unusual for a journal article report no statistical methods for meta-analysis

• Confidence intervals are a vital part of reporting so readers understand the precision of the results

• Measures of heterogeneity (i.e how similar results are across studies) are also vital in meta-analyses. If heterogeneity is high (as it is in this case) the reasons for this should be fully explored

3. Anyone taking an antidepressant will want to know about the benefits and risks associated with the antidepressant they take, not generally with any antidepressant

It is very strange for scientists who understand the nature of withdrawal to not consider this an important element of their aims.

We address the authors’ response chronologically, below, and will post these over the next week or so.

1. Search strategy; we highlighted what we thought was the optimal search strategy, and one that is conventionally applied. We are glad that, on repeating the search no more articles were found. On the point of theses examining the topic, we found a thesis that used survey data in a similar fashion to Read (Thrasher, 2010), that also examined symptoms in people continuing antidepressants and controls, and a number of other studies examining withdrawal symptoms after antidepressant discontinuation. These include studies examining tricyclic antidepressants (Tyrer, 1984).

Again, we really do not wish to “nit-pick” here – our point was that conventional methodology should be applied. The authors make a point regarding use of the PRISMA checklist. Unfortunately, looking at PRISMA, it is clear the authors have not applied this methodology throughout their review (to be covered subsequently).

2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria. The authors state that they have complied with PRISMA, number 6. They have omitted PRISMA number 5, reporting of a protocol registration. The abstract does not mention, in methodology, inclusion criteria, which is suggested by the PRISMA authors, “Study selection statements then ideally describe who selected studies using what inclusion criteria.” (Moher et al, 2009). We would suggest the authors should have put clear inclusion criteria in their Methods section. The reason for this is that it will be important for others to be able to replicate their findings-one of the principles of PRISMA and evidence-based medicine. This would also avoid quibbles about included studies.

It is difficult for the authors to defend this process, which does appear to have “cherry-picked” studies-which is precisely why many systematic reviews publish protocols beforehand, and-at the very least- clearly define inclusion and exclusion criteria a priori.

For example, a study of post marketing safety responses by doctors in the UK reported withdrawal reactions associated with paroxetine in 0.3 per thousand prescriptions, sertraline and fluvoxamine (0.03) and fluoxetine (0.002) (Price et al., 1996). This study is cited for duration, but not incidence, and not for severity. The authors state that paroxetine was reinstated for withdrawal in this study, and this suggests a high degree of severity. In this study doctors were asked to rate severity. The reasons for these exclusions are not explicit.

The authors give reasons for excluding two chart reviews – acknowledging bias with these measures, and length of follow up for one of the studies. It is difficult to understand how they came to this decision for the other study, given that they include other self-report data.

In terms of included studies it is not clear why studies included in Baldwin et al (Baldwin et al., 2007) are not considered. This included the extensive DESS checklist, which puts incidence rates at 1.9-12.2% (placebo), 6.9%-27.3% (escitalopram), 28.4-32.7% (paroxetine) and 31.5% (venlafaxine).

The authors also make comment on exclusion of a study from the incidence section, which showed a rate of 97% withdrawal symptoms. We do not understand how this could even have been thought of as an included study, as it was taken from people who were experiencing withdrawal – a clear example of circularity. This should never have been considered for inclusion – and again, this would be avoided by making inclusion and exclusion criteria clear.

The real question Is how this rudimentary methodological flaw escaped the attention of peer reviewers or the Journal Editor, and we are surprised at the belligerence of the authors in defending these clear breaches of established methodology.

If methodology had been sound there would have been little need to discuss in such depth why some studies were included and others excluded.

We did not set the rules required in putting together a systematic review, and would suggest the authors reflect on why they have not adhered to these.

Further responses to follow.

References

Baldwin, D. S. et al. (2007) ‘Discontinuation symptoms in depression and anxiety disorders’, The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 10(1), pp. 73–84. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705006358.

Garner, E. M., Kelly, M. W., & Thompson, D. F. (1993). Tricyclic antidepressant withdrawal syndrome. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 27(9), 1068-1072.

Moher, D. et al. (2009) ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement’, PLoS Med, 6(7), p. e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000

Price, J. S., Waller, P. C., Wood, S. M., & Mackay, A. V. (1996). A comparison of the post‐marketing safety of four selective serotonin re‐uptake inhibitors including the investigation of symptoms occurring on withdrawal. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 42(6), 757-763.

Thrasher, S. (2010). Collateral damage: A mixed methods study to investigate the use and withdrawal of antidepressants within a naturalistic population.

Tyrer, P. (1984) ‘Clinical effects of abrupt withdrawal from tri-cyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors after long-term treatment’, Journal of Affective Disorders, 6(1), pp. 1–7. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(84)90002-8.

Thank you for this.

I worry how much room there is for evidence of experience under the umbrella of science?

As a philosopher, ethicist, doctor, and once patient, I am going to withdraw from this debate.

My view is that this debate has not shown the best side of the medical establishment: but I wish all the very best.

Kind wishes Peter

“Doubt everything or believe everything: these are two equally convenient strategies. With either we dispense with the need for reflection.” Henri Poincare

3. Assessment of study quality. There are formal approaches to assessing study quality, and it seems again the PRISMA guidance to “describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis” was ignored. It is not that we refuse to acknowledge limitations of the included RCTs, but that Davies and Read provide a disproportionate summary of RCT limitations compared to the survey data. For example, there is no mention of the methods of recruitment into the surveys, the completion rates, or the population sampled from. Again we see this as a breach of the traditional hierarchy of evidence.

Whilst they do suffer from a number of limitations, a major advantage of the placebo controlled RCTs is the ability to be certain that any increase in withdrawal symptoms is attributable to the antidepressant, rather than for some other reason.

4. Conflict of interest. We agree that any researcher could be accused of ideological conflicts of interest, and would urge readers to make up their own minds on this. However, we would hope that most scientists involved in mental health research will maintain clinical equipoise and assess evidence on an issue-by-issue basis. Conflict of interest tends to be defined purely in financial terms and whilst there are increasing discussions about how this definition is too limited, we agree that Journals do not insist on declarations beyond this. We agree the authors have not formally breached guidance.

Our further responses to Davies and Read;

5. Outcome measures.

We are gratified that Davies and Read are now aware of the importance of placebo comparison groups and comparative statistics. It is unfortunate that they did not include this information about the Zajecka et al. study in their published paper. This error of omission is still puzzling. We are unsure of why Davies and Read have yet to address issues regarding the validity of the measures they used to assess withdrawal within their review, the DESS.

6. Measuring severity. Again we wish to reiterate that if the Sir et al. study is a valid assessment of incident withdrawal symptoms, it is illogical that it is not a valid assessment of severity. Our argument is not specifically that severity estimates would have been considerably lower when taken from original studies.

All studies appear of poor quality for assessing severity. Inclusion decisions appear post-hoc and are not in keeping with the principles of PRISMA.

7. Mixing study designs.

We are surprised that Davies and Read assume that we object to inclusion of survey data within systematic reviews.

We did not state this, and do not understand why Davies and Read should choose to misrepresent our statements.

We do not object to the inclusion of surveys, although as we have repeatedly stated the type of surveys included here cannot generate accurate estimates of incidence. The rich quality of the responses to the surveys would have been best analysed using qualitative methods.

We would be grateful if Davies and Read could inform us of how they can arrive at accurate estimates based on this data.

We are heartened at the citing of Egger’s excellent book on systematic reviews, though are unsure why Davies and Read cite it, as it does not justify combining study designs in quantitative analysis. Furthermore, they have ignored sections within the book, on methodology and analysis, and we feel their review and the conclusions it draws are wholly outwith the principles outlined within this book.

Combining of very differ types of studies to arrive at the headline “more than half (56%) of AD users experience withdrawal” is particularly concerning, given we have shown how heterogeneous these estimates are. Davies and Read continue to misrepresent the results from RCTs where the effect truly attributable to withdrawal from antidepressants is the difference between the drug and placebo groups.

It is impossible to justify unscientific methods by comparing erroneous estimates from discrepant study designs, and we are genuinely surprised that Davies and Read continue to believe this is sound methodology.

8. Minor errors. We are concerned that Davies and Read believe “minor errors” in data extraction are not important. We do not “unjustifiably remov[e] all withdrawal symptoms rated ‘minimal’” in the Sir et al. study. We were highlighting Davies and Read’s own inconsistency in reporting this study. The headline (as they state in their response) is that 110 of 129 people experience any level of withdrawal, but when they look at the individual drugs studied they state 39 of 67 people taking sertraline and 44 of 62 taking venlafaxine experience withdrawal. Clearly, 39 plus 44 is 83, not 110 (as we state in the blog). This discrepancy comes from Davies and Read themselves excluding people with “minimal” withdrawal symptoms from these estimates.

Again, we are glad that Davies and Read now recognise the importance of comparison groups when considering if symptoms experienced can be attributable to antidepressant withdrawal. At one week, 27% of individuals stopping the drug and 9% staying on the drug had a DESS score ≥4 (note: this is not a change in DESS score). So 18% may be attributable to the actual drug. At two weeks this difference has reduced to 8% (16%-8%), this data is totally out of keeping with withdrawal being both severe and of long duration.

This appears to be another example of the authors cherry picking results they wish to present, ignoring data they do not agree with, and wholly out of keeping with the established principles of systematic reviews

9. Combining data from different types of antidepressants. As we stated in our introduction to this response “anyone taking an antidepressant will want to know about the benefits and risks associated with the antidepressant they take, not generally with any antidepressant. It is very strange for scientists who understand the nature of withdrawal to not consider this an important element of their aims”. It is perplexing that Davies and Read believe this information might only think this information is useful to “guide clinicians in what drugs to prescribe”.

Davies and Read reiterate their aims in their response

“our aim was to assess whether NICE guidelines (2009) on antidepressant withdrawal were evidence based, not to guide clinicians in what drugs to prescribe nor to illuminate the particularities of different pharmacokinetic properties.”

This statement underlines fatal flaws in the concept of the review.

It is very difficult to state if a guideline is evidence based if one does not either understand or communicate the theoretical basis for that evidence.

In other words, by giving simple answers to complex questions, Davies and Read make cardinal errors throughout their review, and compound this by stating that this was not necessary.

10. Conclusion. Davies and Read state “It is crucial that amid the complexities of academic disagreement we do not lose sight of the scale of the problem.” The scale of the problem is exactly the issue that they fail to address. The methodology they have used to conduct the review, the analyses performed, and conclusions drawn are out of keeping with conventional practice.

The issue of antidepressant withdrawal is a serious issue and requires scientifically sound methodology. We would ask that future reviews adhere to methodologically sound practice and that scientific editors and peer reviewers take some responsibility for ensuring this takes place.

References

Montgomery, S. A. et al. (2005) ‘A 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of escitalopram for the prevention of generalized social anxiety disorder’, The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(10): 1270–1278.

Sir, R. F. et al.(2005). Randomized trial of sertraline versus venla- faxine XR in major depression: Efficacy and discontinuation symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 1312–1320

Zajecka, J. et al. (1998) Safety of Abrupt Discontinuation of Fluoxetine: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study, Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(3): 193.

If I may I would like to offer a few general points to try and move things forward:

(1) In conclusion concern was expressed that “conventional practice” was not followed. However, it is the case that much of trial information remains unpublished and that it is impossible to determine the scale of the involvement of competing financial interests in the studies that are available. These are some of the failings of “conventional practice”.

(2) One of the other failings of “conventional practice” is that it has not been used to study this particular issue with the seriousness it requires. This is demonstrated by the citations provided, most of which are over a decade old.

(3) In Scotland, official figures have revealed that nearly 1 in 5 Scots are taking antidepressants many of them long-term or indefinitely. There is a dearth of evidence to support long-term prescribing. Might this mass prescribing be an indicator that there is a bigger problem with antidepressants than we had previously considered? It is well past the time when “conventional practice” should have been investigating this. I hope that this will now happen and in a collaborative way with those who are taking antidepressants over a longer period than evidence-base supports.

Dr Peter J Gordon

GMC 3468861

29th November 2018.

‘The rules of science’

This comment is based on this interview and debate, aired on ‘All in the Mind’, Radio 4, on Tuesday 27 November 2018. The participants were Dr Sameer Jauhar and Professor John Read:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0001b1p

How many of us, like Dr Jauhar, are today guided by “the rules of science”?

Psychiatrists of my generation were all “educated” about the “chemical imbalance theory” of depression. This was the universal message sold through the pharma-sponsored “Defeat Depression Campaign”. This was presented as a “rule of science” and we were taught that it applied to all!

Today, Dr Jauhar is rightly arguing that Good Medical Practice should be about the individual, and not based on “ideology”.

The most obvious question to ask is why the profession of Psychiatry has NOT looked at prescribing in this individualised way? The opportunity has been there for many decades now.

Today, in Scotland, almost 1 in 5 of our population are taking an antidepressant, often long-term or indefinitely. Yet this long term prescribing has a very poor evidence base.

Meantime, the paid opinion leaders who control the narrative, are currently spending academic and clinical time, looking for novel psychiatric drugs including antidepressants.

Dr Jauhar is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London.. This College is one of several UK institutions that offer “strategic partnerships with industry” and provides a research environment for paid opinion leaders. I called this post “the rules of science” as Dr Jauhar used this term in this interview. This term has also been used in criticism of the methodology used by those studying the issue of antidepressant withdrawal. It is enormously disappointing that influential institutions such as KCL appear to prioritise research into new psychiatric drugs at the expense of any meaningful study of the potential for adverse effects of existing medications. Perhaps this is an example of another “rule of science” namely that research agendas are led by industry?

[this response can be read here along with a short film based on an edit of the All in the Mind broadcast of 27 Nov 2018: https://holeousia.com/2018/11/28/the-rules-of-science/ ]

Dr Peter J Gordon

GMC 3468861

[since my last comment on this post I have resigned from the Royal College of Psychiatrists due to longstanding concerns about lack of full transparency relating to competing financial issues of members. I also resigned as I felt the values of the College were not being upheld by all members]

I suggest you stop trying to rubbish studies that are exposing how horrendously addictive and dangerous SSRI drugs are. Just google all the withdrawal and side effect support groups. They are not there for the fun of it. My life has been ruined by Seroxat; no warning of addiction, side effects or anything. Will never trust any drug or so called dr again. None of them are safe and should never have been released on innocent public. Public safety should be priority not drug company profits.

I wish all studies released for mass public consumption were scrutinized as well as this. The naysaying comments don’t offer what I see as credible opposition, or at least material of any sort. They are attacking the messenger and not the message. If there is false information contained herein, discuss it. Don’t belittle the authors who take on the studies head-on as a sole tactic to undermine the effort.

Dr James Davies and Professor John Read have posted a further response to this blog on the CEPUK website: Tumbling Further Down the Rabbit Hole: the Disturbing World of Antidepressant Withdrawal Research, 8th Jan 2019 http://cepuk.org/2019/01/08/tumbling-rabbit-hole-disturbing-world-antidepressant-withdrawal-research/

Dr Sameer Jauhar and Dr Joseph Hayes have also written a response to the Davies/Read review to the journal who originally published it (Addictive Behaviors). This response will be published soon and we hope to blog about it here on the Mental Elf: The war on antidepressants – What we can, and can’t conclude, from the systematic review of antidepressant withdrawal effects by Davies and Read.

Regarding the position of Drs. Jauhar and Hayes in their recent paper “The War on Antidepressants”, based on the above article:

It is bizarre that a spotlight on a potentially serious adverse effect of a class of drugs is cast as a war on the drugs themselves.

The assumption that antidepressant withdrawal symptoms generally are mild, transitory, and last only a few weeks was promulgated in a pair of supplements to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry in 1997 and 2006 arising from “expert” symposia sponsored by pharmaceutical manufacturers Lilly and Wyeth, respectively, and led by the notorious Dr. Alan Schatzberg.

The conclusions of the “consensus panel” were based only on the opinions of the participants. There was no data or real evidence involved. No citations were given for the statements about the severity of withdrawal syndrome.

These papers are buried in the citations of nearly all other medical literature about antidepressant withdrawal syndrome, with the erroneous assumptions circulated over and over until they calcified throughout psychiatry into “evidence.”

To his credit, one of the experts from Schatzberg’s “consensus panel,” the UK’s Dr. Peter Haddad, repeatedly has made an effort to remedy this misinformation, authoring many papers about withdrawal syndrome and warning about its misdiagnosis. He has pointed out repeatedly that withdrawal symptoms may be relatively mild only in most cases — there are exceptions, the extent of which is unknown.

As Dr. Haddad stated in 2001: “Discontinuation symptoms have received little systematic study with the result that most of the recommendations made here are based on anecdotal data or expert opinion.” (Haddad, P.M. Drug-Safety (2001) 24: 183. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200124030-00003)

I also had personal correspondence in 2006 with another member of the expert panel, Dr. Richard Shelton, who admitted to me that some individuals can suffer severe and prolonged withdrawal syndrome. (Like Dr. Schatzberg, Dr. Shelton went on to a lucrative career as a pharmaceutical company consultant.)

The “experts” who presented their opinions as evidence informing medicine’s assumptions about psychiatric drug withdrawal are well aware they have not disclosed all the risks. Consequently, physicians everywhere have a false sense of safety about these drugs and are blind to the adverse effects.

However, given the extremely high rate of psychiatric prescription, the expedient gloss over the potential of injury has caused damage to millions of people.

In correspondence years ago with Dr. Haddad, he hinted that gathering case histories would be instructive in this debate. On my Web site, SurvivingAntidepressants.org, I have gathered almost 6,000 case histories of difficult psychiatric drug withdrawal, none of them mild, transient, and lasting a few weeks. You can see them here http://survivingantidepressants.org/index.php?/forum/3-introductions-and-updates/

These case histories also demonstrate the many, many ways people are being misdiagnosed and misprescribed. Taken together, they’re a landscape of the pitfalls in medical knowledge regarding psychiatric drugs and their adverse effects.

Another critic of the Read and Davies paper, Dr. Ronald Pies, recently contended in Psychiatric Times (https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/couch-crisis/sorting-out-antidepressant-withdrawal-controversy and comments) that psychiatrists know how to taper people slowly off drugs and therefore serious withdrawal syndrome as reported by Read and Davies is nearly non-existent.

Dr. Pies’s claims are based solely on his own 2012 paper, in its prolix entirety at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3398684/, in which he states:

“In my own practice, I would typically “wean” a patient off a chronically administered antidepressant over a period of 3 to 6 months and sometimes longer. To my knowledge, this period of tapering has rarely, if ever, been used in existing studies of antidepressants or in routine clinical practice.”

Dr. Pies knows very well that “proper psychiatric care” for tapering “managed appropriately” is virtually impossible for patients to find. This tends to confirm Davies and Read are on the right track.

Longer taper periods would definitely be better than the haphazard ways physicians, psychiatrists included, are tapering people now. Calling preliminary investigation into a common adverse reaction a “war on antidepressants” does nothing to advance patient safety. Drs. Read and Davies are correct, we need better ways to taper people off psychiatric drugs.

As authors of the systematic review critiqued by Hayes and Jauhar above, we would like to show here why their critique was often factually incorrect and was replete with misrepresentations (and/or misunderstandings).

The seven points we will make are that Hayes and Jauhar:

1. allege, without justification, incompleteness in our search strategy, while it was as least as thorough as other systematic reviews in this area

2. wrongly claim that data from 5 RCT’s exists when it plainly does not

3. misrepresent or simply misunderstand our exclusion/inclusion criteria

4. appear entirely unconcerned by the bias in the RCTs, while overstating the bias in the surveys

5. wrongly imply we did not declare our conflicts of interest

6. misrepresent or simply misunderstand why RCTs and naturalistic studies did not inform our severity estimates

7. allege data extraction errors we did not make

8. by raising the issue of differences between the drugs, commit the all-too-common fallacy of criticising a study for not doing what it never set out to do

Search strategy

Hayes and Jauhar (2018) allege that it is ‘highly likely’ that our search strategy did not find all relevant studies. We are confident that our strategy, which not only included MEDLINE/PubMed, PsycINFO and Google Scholar, but previous reviews and the bibliographies of 20 relevant papers, is at least as thorough as most systematic reviews with regard to identifying published studies. We have also subsequently searched for relevant unpublished theses, dissertations and conference proceedings, in ProQuest and OpenGrey, and found none.

To support their contention that our search strategy excluded important studies, Hayes and Jauhar pronounce that we failed to include the following five RCTs (i.e. Baldwin et a. 2004a & 2004b; Lader et al. 2004; Montgomery et al. 2003 & 2004). They alleged that these five trials, while primarily focusing on the effectiveness of antidepressants, also contained data on the ‘incidence’ of withdrawal – that is, on how common withdrawal actually is. They contest that if we had included these studies our incidence rates would have been lower, perhaps by around 10%. As this is a core argument of their critique we must inspect it carefully.

Had Hayes and Jauhar read these so-called studies, even cursorily, they would have stopped in their tracks, as we did. Firstly, all five studies were written (either entirely or in part) by employees of Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals (who, in these studies, were researching their own drugs). Secondly, three of the five were not published as studies at all (so we can’t even assess their methodology). Rather they were published as short (300 word) research ‘supplements’ (i.e. industry-funded study-summaries that some journals will publish in return for an industry fee). Needless to say, the obvious conflicts of interests these supplements involve (Lundh et al. 2010) as well as the serious challenges they pose to anyone wanting to assess their methods properly (supplements don’t provide enough detail for that), are just two among numerous ethical and scientific reasons why many credible journals, such as Lancet, now refuse to publish them (Lancet 2010).

Finally, and most damningly for Hayes and Jauhar, none of the five so-called studies contain the incidence data they quote in their critique. To repeat, these five studies do not contain the very data that Hayes and Jauhar alleged we overlooked.

While this, of course, explains why we did not include these studies in our systematic review, it does not explain why Hayes and Jauhar claimed the data were there. We can only surmise that they did not actually check these five studies. Rather, they took the shortcut of quoting a Lundbeck-funded article, published three years later (by Baldwin et al. 2007), which somehow ‘cites’ data from these original five studies that were never included in them.

By basing their arguments on such spurious foundations, Hayes and Jauhar not only demonstrate a concerning lack of caution, but also invalidate many of their core conclusions. For instance, they invalidate their argument that withdrawal incidence rates of 10-12% are not outliers. They also invalidate their re-analysis of overall incidence rates and their pooled figure for incidence from the RCTs (Table 1 of).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Hayes and Jauhar point out that we did not register our inclusion criteria in advance. In response, aside from PRISMA not obliging such criteria to be preregistered (see item #5), we clearly state our eligibility criteria (which complies with PRISMA guideline item #6, while further address PRISMA items 7-10# in the methods section). Additionally, we surpassed most systematic reviews on depression treatments as only a minority (around 30% – Chung et al., 2018) include lists of included and excluded studies, as we do.

Hayes and Jauhar then suggest that we should have identified the length of follow-up, length of antidepressant exposure, and drug-company funding as reasons for exclusion before undertaking the search and data extraction. Firstly, we went beyond both what PRISMA requests and the procedure of previous systematic reviews in this area, by explicitly stating in each relevant section a rationale for excluding each of the studies omitted. Because we did so, any diligent reader will clearly see that none of the three variables that Hayes and Jauhar raise were the sole reason for excluding any study at all (hence our not identifying them as sole reasons for exclusion before our search and data extraction). For example, as the tables make clear, six of the included 24 studies were clearly identified as drug-company funded. Furthermore, the five drug-company studies excluded from our estimate of incidence, while indeed reporting artificially short durations, were excluded on the quite obvious ground that they failed to report incidence rates. This was all plainly stated, even though Hayes and Jauhar wrongly imply otherwise.

Hayes and Jauhar also take issue with our excluding two studies from our estimates of incidence “because they assessed only 9 withdrawal symptoms”. This is, once again, misleading. We did not exclude them on this basis alone but, as explicitly stated, on a variety of methodological considerations. For example, both studies were ‘chart-reviews’ of medical notes, which are notoriously weak owing to their reliance on practitioners being aware of, and recording, withdrawal reactions, while one study, oddly enough, excluded any withdrawal reactions commencing three days after discontinuation.

Finally, we note that Hayes and Jauhar only find reasons to challenge the exclusion of studies with relatively low incidence rates, but do not find fault with, or even acknowledge, our exclusion of a study with a 97% incidence rate.

Assessment of study quality

Hayes and Jauhar state ‘This review does not attempt a traditional assessment of bias in the studies they include’. The methodology of every one of the 24 studies is described, in text and tables, so that readers can assess for themselves their quality, including any sample biases. Furthermore, our ‘Limitations’ section acknowledges the potential minimising bias of the RCTs because of their artificially short treatment and follow-up durations (about which Hayes and Jauhar express no concern), and the possible maximising bias of the surveys because they may attract a disproportionate number of people unhappy with their drugs (about which they express grave concern). We also pointed out, however, that surveys can be prone to bias either way – e.g. one of the largest surveys included contained unusually high proportions of people who thought the drugs had helped them, so it is feasible, in this case, that the sample bias may have been towards people with a generally positive attitude about antidepressants, and therefore the study underestimated adverse effects such as withdrawal. While the RCTs had extremely artificial samples and conditions (and small numbers) the large online surveys, while not necessarily representative of all users (like the RCTs), represented the real life experiences of several thousand people with a range of treatment durations (from weeks to years) and various speeds of withdrawal.

Conflict of interest

Hayes and Jauhar appear to imply that we may have undisclosed ‘ideological’ conflicts of interest, something that can presumably be alleged of any researcher, author or, indeed, blogger in this area. We fully abided by the Conflict of Interest policy of the journal in which we published (Addictive Behaviors, 2018).

5) Outcome measures

Hayes and Jauhar rightly state that in three of the incidence studies that we reviewed some withdrawal symptoms (as identified by the DESS) were also present in some of those continuing to take antidepressants. However, Hayes and Jauhar wrongly claim that in the Zajecka (1998) study withdrawal incidence is ‘higher’ in those continuing to take antidepressants compared to those stopping. The difference between the two overall rates was clearly stated in the study as not statistically different. Furthermore four specific withdrawal effects (dizziness, dysmenorrhea, rhinitis and somnolence) were significantly more common in participants who had come off the drugs. No specific effects were significantly more common in the participants who had stayed on the drugs.

6) Measuring severity

Here Hayes and Jauhar either misrepresent or simply misunderstand the reasons the RCTs and naturalistic studies did not inform our overall severity estimates. Had they read these studies carefully they would have realised that these studies “””did not provide any data on the severity of withdrawal effects””””. The one RCT that did provide severity data (Sir et al., 2005) was, as stipulated, excluded for two reasons: it only covered eight weeks treatment (which would lower severity rates), and because it was a clinician-rated rather than self-report. Hayes and Jauhar choose not to acknowledge that our review also stated that even if we had included this outlier the weighted average of people who described their withdrawal effects as severe would have reduced only slightly, from 45.7% to 43.5%. (i)

Furthermore Hayes and Jauhar misrepresented our 45.7% weighted average by falsely stating that we concluded that ‘The severity of these symptoms is severe in over half of cases’.

7) Mixing study designs (opposition to including surveys)

Hayes and Jauhar argue that it is questionable to combine data from randomised controlled trials and naturalistic studies with survey data. As RCTs and naturalistic studies are regularly covered in systematic reviews (Guyatt et al. 2008; Egger et al. 2001), they obviously object to our inclusion of surveys. In making this objection, however, Hayes and Jauhar are simply confusing a methodological preference with a methodological law. There is no law prohibiting the inclusion of experiential survey data in a systematic review. In fact, given that the design of the majority of RTCs lead to the incidence, severity and duration of withdrawal being minimised (completely failing to capture real world experience of patients), it would have been unethical to omit such experiential data. Psychiatry has too often been guilty of devaluing the importance of experiential knowledge in its evaluation of interventions, which has in turn undermined our capacity to positively intervene.

Even so, given that surveys are open to specific forms of bias, how different would the estimates have been had we omitted surveys from our analysis? The answer is found in noting that the three types of studies, when grouped, did not differ greatly in terms of withdrawal incidence. The weighted averages turn out as follows:

The three surveys – 57.1% (1790/3137),

The five naturalistic studies – 52.5% (127/242)

The six RCTs – 50.7% (341/673)

As getting similar findings from different methodologies is typically seen to strengthen confidence in an overall, combined estimate, it is safe to conclude that at least half of people suffer withdrawal symptoms when trying to come off antidepressants.

Minor errors

Hayes and Jauhar report 3 very minor errors in presentation, which do not impact our estimates. Where we are concerned, however, is that they purport to identify two further ‘errors’, which are clearly not errors at all. For example, their assertion that the ‘total number experiencing withdrawal in the study by Sir and colleagues is 83 rather than 110’ is wrong. They reached this figure by unjustifiably removing all withdrawal symptoms rated ‘minimal’, while not informing readers they did this. This unwarranted decision not only minimised the rate of incidence but also created the false impression that we were in error.

Their second error concerns their suggestion that we misrepresented the incidence rate of another study (Montgomery et al. 2005) by presenting the incidence of withdrawal following escitalopram treatment as ‘27%, when it is 16%.’ Here Hayes and Jauhar again mislead the reader. The 27% rate we reported was at one week and the 16% they reported was at two weeks. Given we were calculating for incidence, it was absolutely correct for us to use the 27% figure in our calculations. These are unfortunate errors for Hayes and Jauhar to make, which, if left uncorrected, would wrongly undermine confidence in our study for some readers.

Combining data from different types of antidepressants

Hayes and Jauhar point out that because medications with longer half-lives will be associated with ‘less’ withdrawal effects “it is puzzling that the results are presented for all antidepressants combined”. Firstly, in the paper we explicitly acknowledge that “differing half-lives affect timing of withdrawal onset”, so they are telling us nothing we don’t already declare. Furthermore, ‘combining results’, or, more accurately, advancing global estimates was both necessary and appropriate given the central aim of our review. To reiterate, our aim was to assess whether NICE guidelines (2009) on antidepressant withdrawal were evidence based, not to guide clinicians in what drugs to prescribe nor to illuminate the particularities of different pharmacokinetic properties. Here Hayes and Jauhar commit the all-too-common fallacy of criticising a study for not doing what it never set out to do.

Conclusion

For the many reasons stated above Hayes and Jauhar’s commentary turns out to be both inaccurate and misleading. In some cases the critiques they offer are based on stark misrepresentations of study findings and/or the misreading or non-reading of primary sources.

Furthermore, we also note that every single criticism, error and/or misrepresentation that Hayes and Jauhar made, resulted in the minimisation (i.e. the downplaying) of both the incidence and severity of antidepressant withdrawal effects. Despite their commentary being biased in this direction, their own re-analysis, which inexcusably includes studies that provide no data on incidence at all, remarkably produces an overall withdrawal incidence rate of 54% (Figure 1), which (despite underestimating the actual rate) would still represent 3.5 million adults in England alone.

We accept that our overall estimates of 56% incidence, with 46% of those being severe, are indeed only estimates. Yet, even if the actual incidence is towards the lower end of the 50% to 57% range, when grouping study types, this would still constitute at least half of all antidepressant users (at least 3.6 million adults in England alone). It is crucial that amid the complexities of academic disagreement we do not lose sight of the scale of the problem that our systematic review helps to expose; a problem predominantly created by the discipline to which both Hayes and Jauhar belong.

In the light of this, it is also interesting to note the absence of any acknowledgment by Hayes and Jauhar that we are discussing a public health issue involving millions of people worldwide. They also fail to comment on the primary finding of the review, namely that national guidelines in the U.S.A. and the U.K. significantly misjudge the true extent of the problem.

In the spirit of seeking some common ground between us, we can agree, however, with one statement Hayes and Jauhar make:

‘It reflects negatively on the whole of the field of psychiatry that there is not better, clearer evidence from high quality studies on the incidence, severity and duration of any symptoms related to antidepressant cessation’ (Hayes and Jauhar 2018).

Given that 16% of the English adult population was prescribed an antidepressant last year alone (7.3 million people), this professional oversight, and its significance, is hard to excuse.

While better research is indeed desirable (with respect to a diversity of issues pertaining to withdrawal), the millions of people experiencing withdrawal effects cannot wait for psychiatry to determine whether they represent 50% or 57% of those withdrawing, or what will be the best methodologies to more precisely assess that. They need accurate information and proper support now. And the millions more who will consider starting antidepressants in the coming years are entitled, unlike those who have gone before, to receive accurate information about all the adverse effects including the difficulty they are very likely to encounter when they try to stop; difficulties that in many cases will be protracted and severe.

A crucial step forward will be for government bodies, and professional organisations, to update their guidelines so as to render them evidence-based, and thereby of maximum benefit to the public.

References:

Baldwin, D.S., Hindmarch. I., Huusom A.K.T., Cooper, J. (2004a). Escitalopram and paroxetine in the short and long-term treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 7 (Suppl. 2), S168–S169.

Baldwin, D.S., Huusom, A.K.T., Mæhlum, E. (2004b). Escitalopram and paroxetine compared to placebo in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). European Neuropsychopharmacology, 14 (Suppl. 3), S311.

Baldwin, D.S., Montgomery, S.A., Nil, R., Lader, M. (2007). Discontinuation symptoms in depression and anxiety disorders. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 10(1):73-84.

Chung, V.C.H., Wu, X.Y., Feng, Y., Ho, R.S.T., Wong, S.Y.S., Threapleton, D. (2018). Methodological quality of systematic reviews on treatments for depression: a cross-sectional study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27 (26): 619-627.

Davies, J., & Read, J. (2018a). A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: Are guidelines evidence-based? (PDF) Addictive Behaviors. Sep 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.027

Davies, J, Read, J (2018b). Antidepressant withdrawal review: authors respond in detail to Mental Elf critique. Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry. Website http://cepuk.org/2018/11/05/antidepressant-withdrawal-review-authors-respond-mental-elf-critique/ (accessed Dec 2019).

Egger, M., Davey-Smith, G., Altman, D. (eds. ) (2001) Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. 2nd ed. London (UK): BMJ Publishing Group.

Guyatt, G., Rennie, D., Meade, M., Cook, D. (2008) Users’ guides to the medical literature. 2nd ed. New York (NY): McGraw Hill Medical.

Hayes, J. & Jauhar, S. (2018) Antidepressant withdrawal: reviewing the paper behind the headlines. Mental Elf. Website https://www.nationalelfservice.net/treatment/antidepressants/antidepressant-withdrawal-reviewing-the-paper-behind-the-headlines/ (accessed Dec 2018).

Lader, M., Stender, K., Burger, V., Nil, R. (2004). The efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram in 12- and 24-week treatment of social anxiety disorder: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study. Depression and Anxiety, 19, 241–248.

The perils of journal and supplement publishing. The Lancet 2010; 375(9712): 347. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60147-X

Lundh, A., Barbateskovic, M., Hróbjartsson, A., Gøtzsche, P.C. (2010) Conflicts of interest at medical journals: the influence of industry-supported randomised trials on journal impact factors and revenue – cohort study. P L o S Medicine. 2 (1);7(10):e1000354. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000354

Montgomery, S.A., Durr-Pal, N., Loft, H., Nil, R. (2003). Relapse prevention by escitalopram treatment of patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD). European Neuropsychopharmacology, 13 (Suppl. 4), S364.

Montgomery, S.A., Huusom, A.K.T., Bothmer, J. (2004a). A randomised study comparing escitalopram with venlafaxine XR in patients in primary care with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychobiology, 50, 57–64.

Montgomery, S., Nil, R., Durr-Pal, N., Loft, H., & Boulenger, J. (2005). A 24-week randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled study of escitalopram for the prevention of generalized social anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 1270–1278

Read, J., Cartwright, C., & Gibson, K. (2014). Adverse emotional and interpersonal effects reported by 1,829 New Zealanders while taking antidepressants. Psychiatry Research, 216, 67–73.

Rosenbaum, J. F., Fava, M., Hoog, S. L., Ascroft, R. C., & Krebs, W. B. (1998). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Biological Psychiatry, 44, 77–87.

Sir, R. F., D’Souza, S. U., George, T., Vahip, S., Hopwood, M., Martin, A. J., … Burt, T. (2005). Randomized trial of sertraline versus venla- faxine XR in major depression: Efficacy and discontinuation symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 1312–1320.

Zajecka, J., Fawcett, J., Amsterdam, J., Quitkin, F., Reimherr, F., Rosenbaum, J., … Beasley, C. (1998). Safety of abrupt discontinuation of fluoxetine: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(3), 193–197.

As a patient advocate and peer counselor for people tapering off psychiatric drugs, I am very puzzled by framing investigation of adverse reactions as a “war on antidepressants” motivated by “ideology”.

Why is it not considered a “war on avoidable adverse effects” motivated by “concern for improving patient care”?

On which side is there ideological blindness? As physicians, are psychiatrists not concerned with continual improvement in clinical practice? Is everything known about psychiatric drugs? Can they do no wrong?

Or is there a suspicion that if assumptions were questioned, clinical practice might be altered for patient safety? Why is that so awful to contemplate?

By the way, just published:

Récalt A, M, Cohen D: Withdrawal Confounding in Randomized Controlled Trials of Antipsychotic, Antidepressant, and Stimulant Drugs, 2000–2017. Psychother Psychosom 2019. doi: 10.1159/000496734

Maybe misdiagnosis of withdrawal symptoms does have extensive repercussions.

[…] (controversial) research has found that when given a scale to describe the withdrawal effect severity, nearly half […]

[…] review article (much criticised) […]