Goffman (1963) defines stigma as the possession of a negative characteristic which discredits and segregates an individual from society. It has been further suggested that there are two distinct types of stigma; public, which refers to stereotypes and prejudices held in the general population and self which refers to the process of an individual becoming aware of these negative stereotypes and applying them to one’s self (Corrigan et al., 2002).

Nine out of ten people who experience a mental health problem report experiencing stigma and discrimination (Corker et al., 2016). This has led to the development of organisations such as Time to Change who aim to alter the way in which people view and discuss mental health problems in the UK.

It has been frequently asserted that the level of stigma experienced can vary depending on the mental health diagnoses an individual has received, with higher levels of prejudice being identified towards those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or substance misuse (Angermeyer & Dietrich, 2006). This issue is a topical one, with the British Psychological Society recently issuing the Power Threat Meaning framework (PDF), an alternative to the historic medical, psychiatric diagnosis system.

To date, qualitative research exploring the subjective experiences of mental health stigma has neglected to focus on the views of those from non-statutory services such as local charities. This has important implications for the findings of such studies, as experiences of stigma and discrimination may be different for people who are not using statutory services.

The current study by Huggett and colleagues therefore aimed to:

examine experiences and views of people with mental health problems, recruited through a local mental health charity, about mental health stigma.

Nine out of ten people experiencing a mental health problem report experiencing stigma

Methods

Two focus groups were conducted with a total of thirteen participants. Participants were mainly White British and aged between 21 and 69, with an even split between males and females.

The authors consulted a patient and public involvement group who aided with study materials and guided on the best way to respond to participants who became distressed during the study.

Focus groups followed a topic guide made up of six key areas:

- Understanding of the term stigma

- Views and experiences of mental health stigma

- Public and internal stigma

- Effects of stigma

- Overcoming stigma

- Priorities for stigma research

The data were analysed thematically.

Results

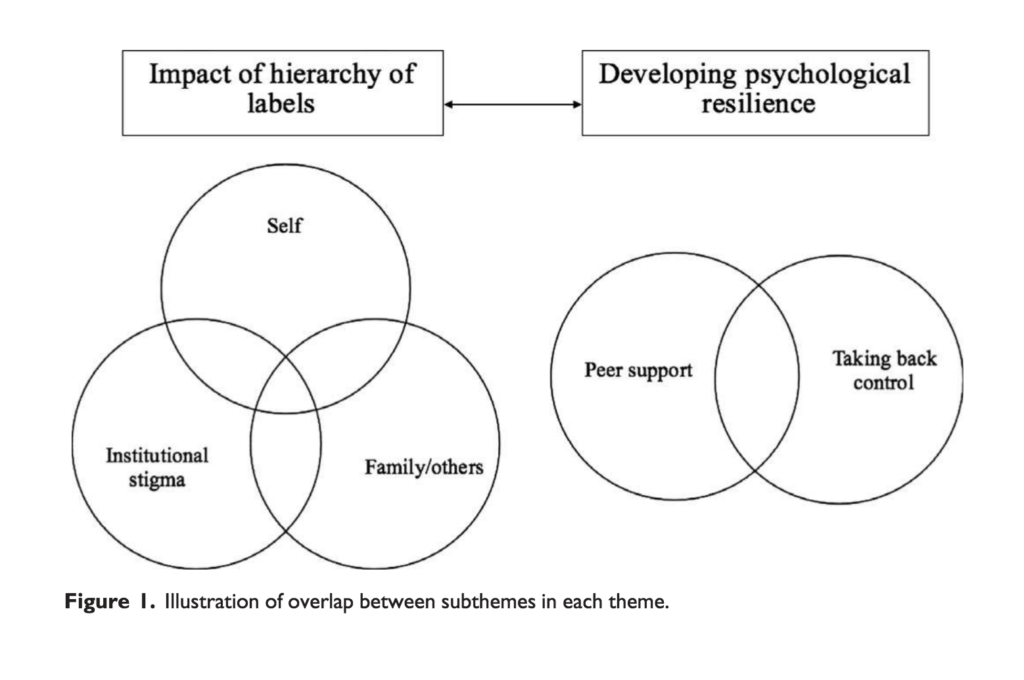

Two themes and five subthemes were identified. These are outlined (see figure 1 below) in a thematic map.

1. Impact of Hierarchy of labels

1a. Self

I think there’s different levels of stigma attached to different diagnoses… If someone said that they had psychosis or schizophrenia, they might get slightly more stigma than someone with depression.

Participants described how prejudiced beliefs held in society about mental health diagnoses could induce self-stigma. Participants asserted that society operates under a ‘hierarchy of stigma’ in which physical illness laid at the bottom, and ‘dangerous’ mental health diagnoses (e.g. schizophrenia) were at the top. Participants stated that these prejudiced beliefs then became internalised, by holding beliefs about one’s self such as “I am mad. I am not normal.” In turn, this led people to feel anxious about sharing their diagnosis with others and to feel angry at themselves.

1b. Expectations from family and friends

I think she was worried, partly because of reactions of the people towards me being open about it. But partly, a personal sense of shame…

Participants described the difficulties faced in disclosing mental health problems to friends and family members, stating that others were often reluctant to allow disclosure of mental health problems and sometimes sceptical of mental health problems. Indeed, disclosing a mental health diagnosis to family and friends was said to result in shame, self-blame and a fear of public reactions in friends and family members. Further, participants explained how disclosing mental health problems to others had resulted in the loss of friendships and consequently led to feelings of abandonment.

1c. Institutional stigma

My GP said the exact same thing to me… I’ve got a diagnosis, but he said that I wouldn’t expect to get a job in mental health if you’ve had mental illness.

Institutions such as hospitals, prisons, councils and the government were perceived as exhibiting ‘institutional’ stigma, which became evident in the policies, procedures and culture of these organisations. For instance, participants discussed how disability assessment centres did not take mental health issues into account when making assessments for benefit entitlements. Participants also spoke about the impact that stigma had on relationships with healthcare professionals, stating that healthcare professionals lacked understanding and distanced themselves.

2. Developing psychological resilience

2a. Taking back control

I am sick of hiding it, and I decided you know what? Yeah, I have got a mental health issue; I shout it off the roof now, because I don’t care.

Despite acknowledging that it was sometimes difficult to disclose mental health problems to friends and family (theme 1b), participants also asserted that doing so could be an empowering exercise, as it demonstrated determination to not be defined by a label. Further to this, participants noted that specific therapies such as person-centred therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy had been useful in curtailing self-stigma.

2b. Peer support

You know that people are all in a similar kind of boat as you and you can feel like you can just relax. But, you’re not alone.

Participants spoke about feeling more comfortable in the presence of others who had mental health problems and felt that these networks helped to develop psychological resilience to overcome stigma. In particular, peer support offered the opportunity to share problems without fear of being stigmatised.

The study participants asserted that society operates under a ‘hierarchy of stigma’ in which physical illness laid at the bottom, and ‘dangerous’ mental health diagnoses (e.g. schizophrenia) were at the top.

Conclusions

This paper has established that there is a perceived hierarchy of stigma based closely on the mental health diagnoses an individual receives, which in turn impacts on stigma from the self, from friends and families and from institutions.

It is encouraging to hear that as well as experiences of stigma and discrimination, participants were also able to identify strategies for overcoming this, including using disclosure of mental health problems as a way to take back some control, and also through discussing mental health problems with peers experiencing similar issues.

Strengths and limitations

This study should be commended for its inclusion of a novel sample of those who are not necessarily engaging with statutory services. As aforementioned, this is important as this group of people may have different experiences and perceptions of mental health stigma.

Further to this, the authors should be commended for their rigour in application of qualitative methods. Similarly, the inclusion of a patient and public involvement group to guide this research should be viewed as a strength of the study, in ensuring that the research remains relevant to the population being studied.

Despite this, within the sample, there was an over-representation of White British participants. This somewhat limits the views to those of one specific culture. This is particularly important in this context, as it is thought that both the amount and nature of mental health stigma can vary between cultures. The study could have been improved by perhaps drawing on the experiences of the patient and public involvement group to identify those groups considered harder to reach (e.g. black and minority ethnic groups).

Summary

This study provides an important account of mental health stigma and discrimination from a population whose voice is often not heard within research; those accessing non-statutory services.

This study found that there is a perceived hierarchy of stigma which is based closely on the mental health diagnosis an individual receives. This is an important finding in the current climate of advocation of a paradigm shift away from medical, psychiatric diagnoses, in the context of the power threat meaning framework.

Should we abandon psychiatric labels in order to reduce the likelihood of stigma?

Links

Primary paper

Huggett C, Birtel MD, Awenat YF, Fleming P, Wilkes S, Williams S, Haddock G (2018) A qualitative study: experiences of stigma by people with mental health problems. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, research and practice. Doi: 10.1111/papt.12167 [PubMed abstract]

Other references

Angermeyer et al (2005) Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: a review of population studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica; 113: 163-179.

Corker et al (2016) Viewpoint survey of mental health service users’ experiences of discrimination in England 2008-2014. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica; 134: 6-13.

Corrigan et al (2002) The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin. Psychol. Sci Pract; 9: 35-53.

Goffman (1963) Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Johnstone et al (2018) The Power Threat Meaning Framework: Towards the identification of patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubled or troubling behaviour, as an alternative to functional psychiatric diagnosis. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

Photo credits

Photo by Ayo Ogunseinde on Unsplash

[…] A hierarchy of stigma based on mental health diagnosis? https://www.nationalelfservice.net/social-care/voluntary-and-community-sector/a-hierarchy-of-stigma-… […]

Thankfully due to social media and other sources, people are slowly taking notice of the sufferings of their friends and families. People are also becoming aware of their own problems and are able to give a name to it. But, there is still much to be done to remove the stigma, and our corporate world can do a lot in that regard.

[…] A hierarchy of stigma based on mental health diagnosis? […]

[…] the perspectives of people being given a diagnosis and the stigma often attached to this (Hemming, 2018; Huggett et al., 2018; Sheffer et al., […]