In the UK, there has been a drive since the second half of the twentieth century to help people move on from long-term hospital stays to live in the community. This ‘deinstitutionalisation’ responded to the environmental poverty of long stay wards (Wing and Brown 1970), and resulted in a vast reduction in hospital inpatient beds (>150,000 in 1955 to <3,000 by 2012) (Shepherd G and Macpherson 2011). For more on this subject, check out the #MindStateSociety podcast recorded earlier in 2020.

Approximately 84,000 people live in specialist mental health supported accommodation in England (Killaspy and Priebe 2020); fascinatingly, the evidence base for this (expensive) residency is hugely limited (McPherson P et al 2018).

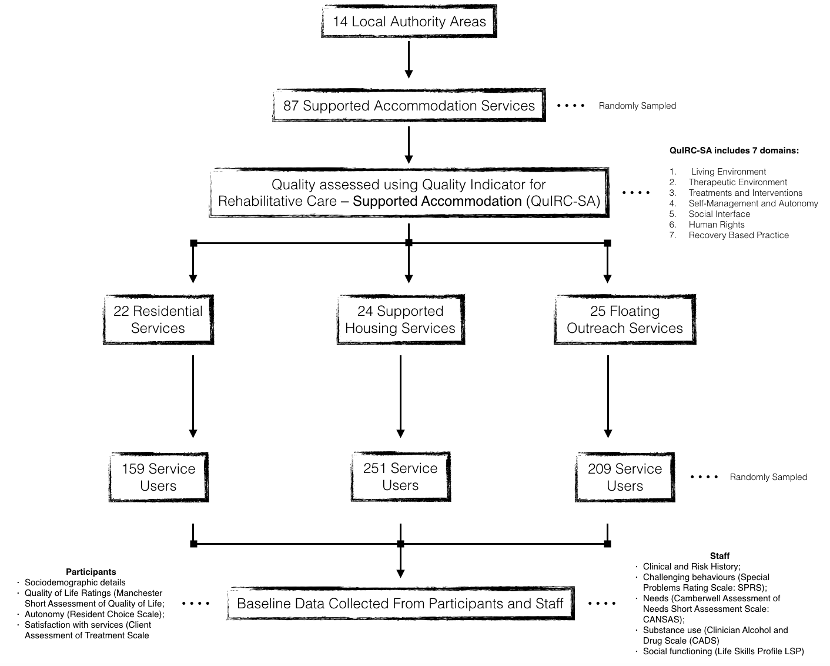

Thankfully Prof Helen Killaspy and her colleagues aimed to rectify this with the QuEST (Quality and Effectiveness of Supported Tenancies for people with mental health problems) research programme.

This research characterised accommodation into:

- Residential care

- Non-time-limited communal placements

- Needs provided by on-site staff 24/7

- Supported housing

- Time-limited shared or individual self-contained tenancies

- On-site staff up to 24 hours a day, support increasing functional independence

- Floating support

- Non-time-limited, self-contained tenancies

- Offsite staff support via limited visits.

As individuals’ skills improve they can move towards less supported accommodation and increased independence.

The study aimed to answer:

- What proportion of residents moved on and sustained more independent accommodation?

- How much variation was due to service type and quality?

There is a dearth of research evaluating the effectiveness of supported accommodation provision.

Methods

- Accommodation quality was scored using the QuIRC-SA

- Three-monthly data collection on accommodation change / hospital admission

- Thirty-month telephone interviews with staff or clinical record review

- Costs estimated through the Client Service Receipt Inventory including one-one and group contact, and length of inpatient stay.

Primary outcomes

- The primary outcome of ‘successfully moving on’ was defined as: “the proportion of participants who moved to more independent accommodation without placement breakdown over the 30-month follow-up period” and for those participants living in floating outreach as: “managing with fewer hours of support per week”

- Univariate analysis identified significant service and service-user variables

- Sensitivity analyses tested confounders such as demographic and clinical data; to nuance floating outreach data, a cut-off of 50% reduction in hours was applied

- The proportion successfully moving-on without hospital admission was calculated as a secondary outcome

- Care cost analysis was applied to the above.

Prospective QuEST cohort followed up for 30 months (Figure 1). Click image to see full size graphic.

Results

- 586 of 619 participants (95%) were followed-up

- 243 (41.5%) achieved the primary outcome of moving on to ‘less supported accommodation’, with significant differences between them:

- 15 out of 146 (10.3%) residential care service users

- 96 out of 244 (39.3%) in supported housing

- 132 out of 196 (67.3 %) of those in floating outreach

- QuIRC-SA scores showed human rights and recovery-based practice were associated with favourable outcomes, but interestingly, positive social interface scores had a negative impact

- Only 17 of the 243 (7%) who moved on to less supported accommodation had a hospital admission

- Residential care was on average about twice as expensive as alternatives; broad confidence intervals meant this was not a significant finding once demographic and clinical variables were accounted for

- Accounting for these variables, participants costs were (on average: mean) £427 lower for those that did move on, than those who did not, and similarly their adjusted inpatient costs were on average £14,608 less than those who did not.

Less than half of the service users achieved the primary outcome of ‘moving on to less supported accommodation’.

Conclusions

- 42% of participants moved on. This was not evenly distributed between services:

- one-tenth of those in residential care moved to lesser support

- a third of those in supported housing

- two-thirds of participants in floating outreach services

- Service user characteristics negatively impacting moving reflected increased morbidity: unmet needs, greater risks and longer length of prior stay

- Services that promoted service users’ human rights (protection of dignity and advocacy) and adopted recovery-based practice were associated with moving on

- ‘Social interface’ (i.e. family involvement and engagement with community resources) was negatively associated with moving on. This apparent paradoxical finding was argued due to some families’ resistance to relatives moving to more independent settings, or users resisting moving from areas they have become invested in

- Moving on was significantly associated with reduced inpatient admissions and overall service costs

- Finally, a third of those in the supported housing user group (and 16% of the whole sample) were considered ready to move on by staff despite having not done so.

Promotion of human rights and adoption of recovery-based practice by services was associated with successfully moving on.

Strengths

- The authors and the QuEST programme should be congratulated for undertaking real world research on a costly intervention that suffers from a surprising dearth of evidence, but upon which so many service users depend

- A follow up rate of 95% for primary outcome data is to be commended

- Use of random English local authorities reflects a helpful generalisability to the results nationally

- Sensitivity analysis was applied to explore for potential confounding.

Limitations

- The authors acknowledge their definition of ‘moving on’ for floating outreach was likely an easier-to-achieve outcome. Too little is made of the fact that only 15 of 146 participants moved on from the highest (and most costly) form of support during this time

- This type of research is hampered by confounders and the type of accommodation provider was not included in the analysis. Private facilities may lack financial motivation to move people on. The impact of personality domains would also have been interesting

- The programme had designed its own quality indicator through adaption of a rehabilitative tool

- Moving on without subsequent hospital admission was said to be significantly more likely with more independence of service. From the statistics provided I cannot see how this can be the case when 0/15 who moved on from residential care were subsequently admitted. A question there for the authors please.

Type of accommodation provider whether private, public or third-sector was not considered as a potential confounder.

Implications for practice

- My clinical experience speaks to the variability of service provision, costs and unclear criteria. The QuEST programme as a whole represents a necessary foray into establishing a better evidence base for specialist mental health accommodation

- The results suggest that the majority of individuals may require longer than the Government’s short-term supported accommodation model where services are contracted for two years; the majority of participants had ‘not moved’ on in two and half years. The current model may need to be reviewed

- The QuIRC-SA is a tool that can be used to assess supported accommodation quality. Human rights and recovery-based practice quality domain were associated with successfully moving on. Details of these domains should be shared widely between services

- A proportion of service users were considered ready to move on but hadn’t. The authors suggest this reflects a national under provision of accommodation. This may be only one of the barriers to moving on; others should be explored. For example this study suggests family involvement may hamper moving on. Might early discussion with family about the goals of such placements ease understandable anxieties? The cost implications are significant given the study’s finding of markedly lower costs on average for those who had moved on

- A majority of service users had not moved on at 30 months. Without increased provision and research investigating bottlenecks, I fear we will continue with the back-up in acute hospitals that I witness as a clinician; previously referred to as the ’new long-stay patient’ (Mann and Cree 1976).

The majority of people who need specialist mental health supported accommodation may require longer than the Governments’ 2 year short-term supported accommodation model.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

Killaspy, H., Priebe, S., McPherson, P., Zenasni, Z., Greenberg, L., McCrone, P., . . . King, M. (2020). Predictors of moving on from mental health supported accommodation in England: National cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 216(6), 331-337. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.101

Other references

Wing JK and Brown GW (1970) Institutionalism and schizophrenia: a comparative study of three mental hospitals 1960–1968. Cambridge University Press.

Shepherd, G. and Macpherson, R. (2011) Residential Care. Chapter for Oxford Textbook of Community Mental Health. Oxford University Press.

Killapsy H and Priebe S, Research into mental health supported accommodation – desperately needed but challenging to deliver. The British Journal of Psychiatry (2020) Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 April 2020

Mcpherson P, Krotofil J, Killaspy H. Mental health supported accommodation services: a systematic review of mental health and psychosocial outcomes. BMC Psychiatry 2018; 18, 128

Killaspy H, Priebe S, Bremner S, McCrone P, Dowling S, Harrison I, et al. Quality of life, autonomy, satisfaction, and costs associated with mental health supported accommodation services in England: a national survey. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3: 1129–37.

Killaspy H, White S, Dowling S, Krotofil J, McPherson P, Sandhu S, et al.Adaptation of the Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care (QuIRC) for use inmental health supported accommodation services (QuIRC-SA). BMC Psychiatry 2016; 16: 101.

Mann and Cree (1976) “New” long-stay psychiatric patients: a national sample survey of fifteen mental hospitals in England and Wales 1972/3. Psychological Medicine. 1976; Nov; 6(4):603-16.

Quick response to the query about moving on without subsequent admission – the ORs reported refer to the secondary outcome which was a composite of both moving on and not having a subsequent admission. Move on was much lower from residential care than supported housing and lower from supported housing than floating outreach. There were few admissions after move on from any type of supported accommodation so even when taking account of admissions as a marker of ‘successful move-on’ we found a similar pattern to our primary outcome with greater successful move on from more independent settings.

The other query about possibility of financial disincentives for move on is probably only relevant to a few residential care homes as most of the supported accommodation providers studied were not private organisations.