In light of the continued and increasing attack by the American administration on trans Americans, I am grateful for the opportunity to write about trans-affirmative American research on the International Transgender Day of Visibility (31 March 2018).

When colleagues and friends discover that I have an interest in transgender health, the questions that follow are often similar. Not uncommon among them are queries of when a young person’s trans identity is seen as valid and when they can begin transition. These queries and many others surrounding child and adolescent gender are sensitively discussed in Jack Turban and Diane Ehrensaft’s recent Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry research review: Gender identity in youth: treatment paradigms and controversies (Turban and Ehrensaft, 2017).

At what point is a young person’s trans identity seen as valid?

Methods

The authors refer to the paper as a ‘critical review of the extant literature, both theoretical and empirical’. Unfortunately, it is not possible to comment any further on the methodology as there is no description of the search terms, databases or inclusion criteria for papers examined by the authors.

Results

- Studies in San Francisco (n= 2,730) and New Zealand (n= 8,166) report a prevalence of transgender identity of 1.3% and 1.2% respectively, among adolescents (Shields el al., 2013; Clark et al., 2014).

- Birth assigned males were found to be more likely to present to gender clinics at prepubertal ages, with the ratio of birth assigned genders becoming equal in adolescence.

- Internalising psychopathologies are common among transgender youth, increasing with age as minority stress and gender dysphoria accumulate. Prevalence of these mental health conditions is estimated as 12-64% (mood disorders) and 16-55% (anxiety disorders).

- Poor peer relations were found to be a significant predictor of internalising psychopathology, suggesting that external and not internal conflicts were responsible for aforementioned dysphoria (de Vries et al., 2016).

- The authors comment on research which shows that trans youth are at increased risk of suicidality as early as age 5, with risk increasing with age (Aitken et al., 2016) and family non-acceptance of trans identity (Grant et al., 2011).

- The authors report on research showing an increased prevalence of autism spectrum disorder symptoms among gender clinic-referred youth. However, Strang et al., 2014 note that this apparent relationship may be due to the overrepresentation of gender dysphoria in clinic-referred populations generally.

- Gender diversity is likely the result of a combination of biological and sociocultural determinants. All psychosocial factors can be alternatively interpreted as symptomatic of and not causal in gender dysphoria.

- Transgender children who are allowed to undergo social transition have rates of depression, anxiety and self-worth similar to cisgender counterparts (Durwood et al., 2017; Olson et al., 2016).

- Pubertal blockade with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRH) at Tanner stage 2 or 3 can safely allow transgender youth the time to consider further (more permanent) treatment options carefully, in the absence of gender dysphoria.

- It is noted that whilst cross sex hormone therapy is known to diminish fertility, further research is needed to determine longitudinal fertility desires of transgender youth.

- The authors comment that most surgeries are reserved for adulthood. However, the most recent version of the WPATH SOC and the Endocrine Society Guidelines note that chest surgery may be considered earlier in some cases (Coleman et al., 2011; Hembree et al., 2017).

- The complex intersectionality of race, religion and gender must be considered on an individual basis. For example, trans and gender non-conforming individuals may be stigmatised to a greater or lesser extent depending on cultural and religious surroundings. Similarly, an individual in the LGBT+ community may experience discrimination as a consequence of their ethnicity or faith (Webster & Telingator, 2016).

The complex intersectionality of race, religion and gender must be considered on an individual basis.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that:

affirmative care, in which a youth is supported in living in the gender that feels most authentic, results in good mental health outcomes… Accompanying psychological issues, notably internalising psychopathology, are largely driven by stigma and lack of affirmation… they are socially induced by a nonaccepting environment.

Strengths and limitations

This article is very comprehensive in so far that it considers many aspects of the discussion on gender identity in youth, from a number of perspectives. Conversely, the search terms and databases used as well as inclusion criteria for any papers to be discussed are not disclosed and so it is not possible to determine how robust this methodology has been. This seemed particularly problematic when quoting prevalence rates throughout the paper, where one investigator’s estimate may differ greatly from that of another.

In a recent Mental Elf article, I have referred to the search for an ‘aetiology’ for trans identities as a ‘fundamental flaw’ of research of this kind (Connolly, 2018). I stand by that argument again and feel that exploration of determinants of non-cis genders contributes to unnecessary pathologisation of a characteristic fundamental to a person’s sense of self. In this article, I believe the presentation of social theories only to then refute them on the basis of causality is a waste of both author and reader time. I am particularly concerned by the inclusion of this section when the authors have gone to such labour to stress the point that anything but affirmation and support can create internal conflict and lead to poorer mental health outcomes for young people.

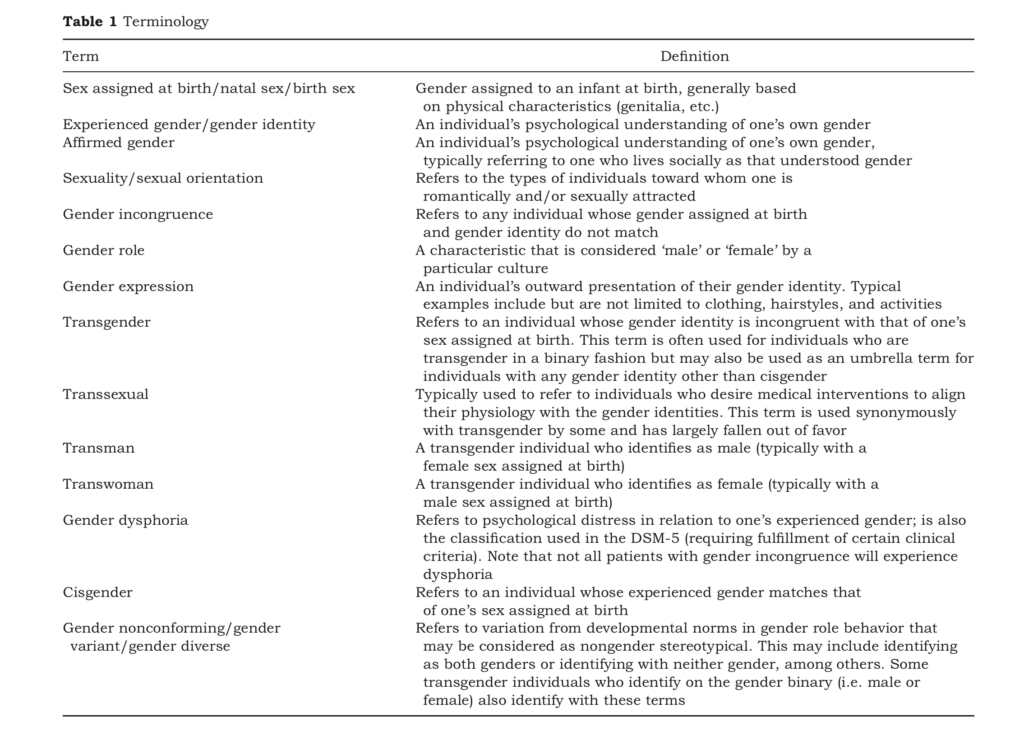

The sensitive use of language throughout the review is a marked improvement upon other research in the area. Indeed, the authors reflect on the constant evolution of language within the field and the need to be aware of that when interacting with vulnerable young people. Furthermore, the authors include a table of terminology as a reference guide, which I recommend as a starting point for those working with trans and gender diverse youth.

Implications for practice

The review finds that pubertal blockade, cross sex hormone treatment and gender affirming surgery result in “improved mental health and ultimate global functioning and life satisfaction on par with the general population” (deVries et al., 2014). This, combined with the aforementioned finding that internalising psychopathologies accumulate with time resulting in greater rates of suicidality, provides a strong basis for encouraging clinicians to refer early to gender services, as outcomes are clearly time sensitive.

It is also important that clinicians explore race, religion and additional cultural factors that can intersect to either complicate or facilitate a young person’s transition. An understanding of these factors will allow reasonable goals to be set as well as guide the involvement of other services.

It’s important that clinicians explore race, religion and additional cultural factors that can intersect to either complicate or facilitate a young person’s transition.

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Links

Primary paper

Turban JL, Ehrensaft D. (2017) Research Review: Gender identity in youth: treatment paradigms and controversies. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12833

Other references

Shields, J.P., Cohen, R., Glassman, J.R., Whitaker, K., Franks, H., & Bertolini, I. (2013). Estimating population size and demographic characteristics of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth in middle school. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 248–250.

Clark, T.C., Lucassen, M.F., Bullen, P., Denny, S.J., Fleming, T.M., Robinson, E.M., & Rossen, F.V. (2014). The health and well-being of transgender high school students: Results from the New Zealand adolescent health survey (Youth’12). Journal of Adolescent Health, 55,93–99.

de Vries, A.L., Steensma, T.D., Cohen-Kettenis, P.T., Van-derLaan, D.P., & Zucker, K.J. (2016). Poor peer relations predict parent- and self-reported behavioral and emotional problems of adolescents with gender dysphoria: A cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25, 579–588.

Aitken, M., VanderLaan, D.P., Wasserman, L., Stojanovski, S., & Zucker, K.J. (2016). Self-harm and suicidality in children referred for gender dysphoria. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55, 513–520.

Grant, J.M., Mottet, L., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J., &Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of thenational transgender discrimination survey. Washington,DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and NationalGay and Lesbian Task Force.

Strang, J.F., Kenworthy, L., Dominska, A., Sokoloff, J., Kenealy, L.E., Berl, M., … & Luong-Tran, C. (2014). Increased gender variance in autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1525-1533.

Durwood, L., McLaughlin, K.A., & Olson, K.R. (2017). Mental health and self-worth in socially transitioned transgender youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 116–123. e2.

Olson, J., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., & McLaughlin, K.A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics, 137,1–8.

Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., & Zucker, K. (2011). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender and gender non-conforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13, 165–232.

Hembree, W.C., Cohen-Kettenis, P.T., Gooren, L., Hannema, S.E., Meyer, W.J., Murad, M.H., … & T’Sjoen, G.G. (2017). Endocrine treatment of gender dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 102,1–35.

Webster, C.R., Jr, & Telingator, C.J. (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families. Pediatric Clinics North America, 63, 1107–1119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40732492?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Connolly D. Mental illness and neurobiological correlates in the transgender population. The Mental Elf, 16 Feb 2018.

Important guidance and support services

- World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standard of Care – https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc

- http://www.mermaidsuk.org.uk/ – Family and individual support for gender diverse and transgender children and young people.

- www.stonewall.org.uk – Information and support for the LGBTQ+ community and their allies.

Photo credits

- Photo by Anton Darius | @theSollers on Unsplash

- Photo by Warren Wong on Unsplash

- Ted Eytan CC BY 2.0

- Photo by Dariusz Sankowski on Unsplash

[…] Gender identity in young people: determinants, epidemiology, mental health and management […]