Just over a decade ago, a research study of rural mental health services in the north Midlands of the UK, recognised the importance of community mental health services and workers operating in a sensitive, non-stigmatising way (Crawford and Brown, 2002). The study made the connection between mental health stigma and service use. The authors described mental health stigma as traditionally being:

…seen as something that is the fault of the mental health system, and that involves an individual suffering social disapprobation and reduced life chances as a result of having been given a diagnostic label and an identity as a patient as a result of their contact with psychiatric institutions. (Crawford & Brown 2002 p229)

In a recent Mental Elf blog, Nikki Newhouse covered research from the Mental Health Commission of Canada that suggested that the stigma of mental illness is a barrier to care and help seeking. In the research, people with mental health problems said that at times ‘the stigma is worse than the illness’. Nikki mentioned the study summarised in this blog, which further explores the associations between the stigma of mental illness and people seeking help for their mental health problems. This study is the first systematic review of research looking at the impact of mental health stigma on help-seeking behaviour. The authors aimed to investigate the following questions:

- What is the size and direction of the association between stigma and help-seeking?

- To what extent is stigma identified as a barrier to help-seeking?

- What processes underlie the relationship between stigma and help-seeking?

- Are there population groups for which stigma disproportionately deters help-seeking?

They focused on help seeking from formal mental health services in the healthcare sector and from talking therapy services.

This study set out to explore the relationship between stigma and help-seeking behaviour

Methods

Five electronic databases (Medline, EMBASE, Sociological Abstracts, PsychInfo and CINAHL) were searched for studies and reviews on associations between stigma and help-seeking, dating from 1980 until 2011. There were no language restrictions in the searching. Following screening, 144 studies were included in the review. Three main types of literature were identified:

- Quantitative association studies, giving statistical data the relationship between measurements of stigma and help-seeking

- Quantitative barrier studies, giving data on the proportion of participants experiencing stigma-related barriers to help-seeking

- Qualitative process studies, giving analyses of interviews, focus groups or observational studies about stigma and help-seeking

Studies on structural stigma, such as lower funding and status accorded to mental health services or negative media stereotypes were not included.

Results

The majority of studies (69%) were undertaken in US or Canada, with 20 being conducted in Europe; 10 in Australia and New Zealand; 8 in Asia and 1 in South America. 21% of the studies were on students in higher education. The included studies were judged to be of methodologically mixed quality. Using key themes from the qualitative process studies, the authors constructed a conceptual model showing the relationship between the processes contributing to and counteracting the effects of stigma on help-seeking behaviour. The five major themes were:

- Dissonance between a person’s preferred self-identity or social identity and common stereotypes about mental health

- Anticipation/experience of negative consequences

- Need/preference for non-disclosure

- Stigma-related strategies used by individuals to enable help-seeking

- Stigma-related aspects of care that facilitate help-seeking

Notable sub-themes included ‘stigma for family’ for people from black and minority ethnic communities and ‘fear of psychiatric patients’, a barrier-related theme arising from the quantitative studies. Overall, the systematic review yielded these main findings:

- “Stigma was the fourth highest ranked barrier to help seeking [out of ten], with disclosure concerns the most commonly reported stigma barrier”

- “Ethnic minorities, youth, men, those in the military and health professionals were disproportionately deterred by stigma”

- “Stigma had a moderate effect on help-seeking compared to other types of barrier”

The authors also noted that seeking help from mental health services could be stigmatising and highlighted the negative effects of internalised stigma, or feelings of shame about having a mental health problem.

-

This review concluded that stigma has a small- to moderate-sized negative effect on help-seeking

Conclusion

The review authors conclude that:

Stigma has a small- to moderate-sized negative effect on help seeking. Review findings can be used to help inform the design of interventions to increase help-seeking.

For applying this research evidence in practice, they recommend that for interventions to improve access to mental health care and support:

multiple different types and aspects of stigma contribute to this effect, consequently multi-faceted approaches are likely to be most productive.

Summing up

This systematic review has some important limitations to consider when thinking about the generalisibility of findings. Firstly, the majority of included studies were carried out in Western countries with particular understandings of mental health and health and social care systems. Therefore mental health stigma and help-seeking was framed within the experience and values of those countries. The authors note that the exclusion of ‘grey literature’ represents a possible publication bias and that the fact that studies looking at ‘structural stigma’ were excluded may have resulted in an incomplete picture. Nearly a quarter of the studies had students as participants.

Despite these limitations, the study suggests that the stigma of mental illness itself can effect help-seeking from mental health services, implying that using mental health services can be stigmatising. This barrier has the potential to result in a cycle where mental health deteriorates because help is not sought and stigma increases as a result. Stigma is revealed to be a complex experience, with various effects on help-seeking for different people. The combined effect of social discrimination and/or stereotypes and mental health stigma is suggested by the profile of people who are disproportionately deterred from seeking help from formal mental health services by stigma. As such, the authors recommend that:

Services and practitioners could…support service users to develop additional strategies to cope with, and counter, treatment stigma and to address internalised stigma.

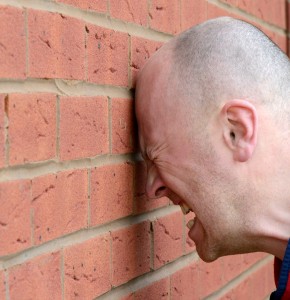

The fear of stigma can prevent some people from seeking the help of mental health services

Links

Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Morgan C, Rusch N, Brown S J L, Thornicroft G (2014) What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies Psychological Medicine doi: 10.1017/S00332917140000129 [PubMed abstract]

Crawford P & Brown S (2002) ‘Like a friend going round’: reducing the stigma attached to mental healthcare in rural communities (PDF). Health and Social Care in the Community 10(4) pp.229–238

Does stigma impact on help seeking behaviour?: Just over a decade ago, a research study of rural mental health… http://t.co/XpUDRREOOH

Stigma is a snobbish issue, i don’t feel stigmatised against, ever, unless I come into contact with a phoney professional, like a doctor

“@Mental_Elf: Does stigma impact on help seeking behaviour? http://t.co/N5Q5K7CH4Z”particularly relevant for EIS clients

Services should support users cope with mental health stigma and address internalised stigma http://t.co/fnJexY1gVt http://t.co/VdDU8FeNc7

Today @SchrebersSister blogs about the relationship between stigma and help-seeking behaviour http://t.co/eQUC6NnsQS

@Sectioned_ #headclutcher has morphed into #headbanger – not sure this is a positive step forward http://t.co/h4cGIefxs2

Stigma is a complex issue

Q. Does stigma impact on help seeking behaviour? A. It can: http://t.co/YMHdK83F8S via @sharethis Latest research summary from @Mental_Elf

Mental Elf: Does stigma impact on help seeking behaviour? http://t.co/BLBSaf33PM

Does stigma impact on help seeking behaviour? Write up/review by @Mental_Elf http://t.co/G7A4LrtFX6

RT @Mental_Elf: Has stigma prevented you from seeking help for your mental health problems? Please share your experiences on our blog http:…

Systematic review finds that the fear of stigma can prevent people from seeking the help of mental health services http://t.co/eQUC6NnsQS

And in “No shit, Sherlock” news

MT @Mental_Elf fear of stigma can prevent people from seeking mental health services http://t.co/2EQYTougcV

study set out to explore the relationship between stigma and help-seeking behaviour http://t.co/3GUWZrnWig

Don’t miss: Does mental health #stigma impact on help seeking behaviour? http://t.co/eQUC6NnsQS

@Mental_Elf #Intersection culture, poverty, gender & stigma powerful barrier to help-seeking for mental illness http://t.co/on2TAfaEXH

@Mental_Elf @nurse_w_glasses Of course!! Just like sexual health problems or obesity

RT @Mental_Elf: Stigma has a negative effect on help-seeking behaviour http://t.co/eQUC6NnsQS

RT @Mental_Elf: Most popular blog this week? It’s @SchrebersSister on how stigma can impact on help-seeking behaviour? http://t.co/eQUC6Nns…

.@Mental_Elf The stigma of a MH dx can be worse than the ‘illness.’ Article fails to draw the obvious conclusion http://t.co/ROpvDw4YuY

@ClinpsychLucy @Mental_Elf For me, it was the labelling, and effects of heavy drugging, that brought the stigma.

@jeandavisonTDT @Mental_Elf In other words the standard treatment This merits a better response than ‘we must teach people to deal w stigma’

@jeandavisonTDT @ClinpsychLucy @Mental_Elf Valuable blog & discussion. Need move away from dx. Validate individual exp ought remove stigma?

Stigma is complex. Takes many forms. Intersection of ethnicity, culture, disadvantage, and gender increases risk of stigma and creates powerful barrier to help-seeking for mental illness mental http://journals.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleid=98866

. @SchrebersSister Interesting comment and link from @EdgeDawn on your blog: http://t.co/zAUqqC7dSs

@Mental_Elf TY @EdgeDawn for alerting us to this US research on #BME women, stigma & help-seeking for #mentalhealth http://t.co/hfXTcAtraD

Can stigma impact on help seeking? Let’s also ask, Can help seeking impact on stigma? For me, it was the labelling and effects of heavy drugging that brought the stigma.

@mental_elf: Review finds that the fear of stigma can prevent people from seeking help of MH services http://t.co/XpoWfbhkVc

#EndStigma

Does stigma impact on help seeking behaviour? – The Mental Elf http://t.co/F2xyCiMCx8

Does #mentalhealth stigma impact on help seeking behaviour? http://t.co/OuHY5qrTb5

[…] mental health service use to stigma and how stigma relates to help-seeking behaviour. I wrote a blog about another systematic review concerning this topic a while ago and wondered how the findings on […]