Data from the largest and most comprehensive survey of causes of illness worldwide has been published in the Lancet.

This paper represents the latest analysis of the data set collected in the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2010 (GBD 2010) and focuses on the global burden of illness due to mental disorders and substance abuse.

A previous analysis has looked at the burden of illness particularly in the UK.

Methods

As part of the GBD 2010, epidemiological data was collected for 20 mental and substance abuse disorders in 187 countries. This allowed the authors of the study to model the burden of disease in these countries.

The burden of disease was calculated using three metrics:

- Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)

- Years of life lost to premature mortality (YLLs)

- Years lived with disability (YLDs) – defined in the previous post on the Global Burden of Disease Study

Results

The biggest finding in this analysis is that mental and substance abuse disorders were the leading cause of non-fatal illness worldwide in 2010. Overall, these disorders accounted for 22.8% of non-fatal illness worldwide.

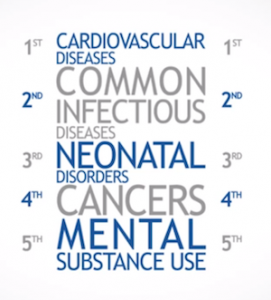

Mental and substance abuse disorders were the fifth leading cause of death and disability worldwide

Mental and substance abuse disorders were the fifth leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Only cardiovascular disease and infectious diseases were responsible for significantly more death and disability than mental and substance use disorders globally.

Mental and substance use disorders were responsible for a similar burden of illness as cancer, and neonatal disorders and were responsible for a greater burden of illness than HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and diabetes.

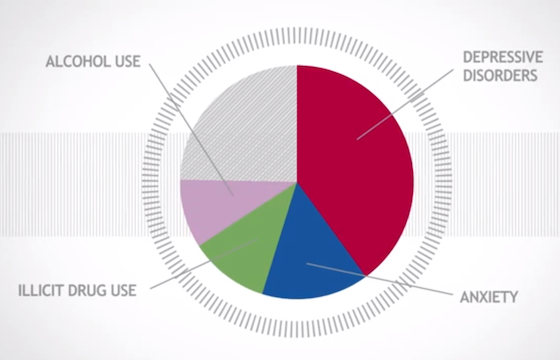

Depressive disorders were responsible for 40% of the burden of illness due to mental and substance abuse disorders.

Other findings included:

- In people over the age of 10, girls and women had a higher incidence of death and disease from mental disorders than did boys and men, whereas men had higher drug and alcohol dependence in all age groups

- Overall findings mask marked differences between different regions of the world:

- For example, eating disorders show the greatest overall variation between different regions of the world. The region of the world where they were highest – Australasia – showed a forty times higher incidence than the region of the world where incidence was lowest – western sub-Saharan Africa

- Although, in some cases, the similarities between different regions are more striking than the differences – only China, Japan, Nigeria and North Korea had significantly lower burdens of death and disease from mental and substance abuse disorders than the global average

- The burden of mental and substance use disorders increased by 37·6% between 1990 and 2010, which was mostly due to population growth and ageing

Depressive disorders were responsible for 40% of the burden of illness due to mental and substance abuse disorders

Limitations of the study

Data from some world regions (notably sub-Saharan Africa, parts of Asia, and central and eastern Europe) were scarce, resulting in greater statistical uncertainty over the estimates for these regions and the need for statistical imputation of some data points.

Individuals in some cultures interpret and express symptoms of mental disorders differently from the descriptions used in DSM/ICD diagnostic criteria likely contributing to differences in rates of diagnosis in different cultural groups.

In GBD, deaths are coded according to the physical cause of death and this may mask the number of premature deaths due to the presence of mental illness: deaths by suicide are coded under injuries, even though in most cases these deaths occur in the context of mental illness; and deaths from illicit drugs are often coded under accidental poisonings.

As with all studies measuring chronic disability – and using the disability-adjusted life years metric – there is subjectivity to the measurement. How disabling different conditions are was determined by online and face-to-face questionnaires with 30,000 people around the world.

Conclusions

The authors of the paper conclude that mental and substance use disorders are major contributors to the global burden of disease and their contribution is rising, especially in developing countries.

The authors throw down the gauntlet at the feet of public health officials:

Cost-effective interventions are available for most disorders but adequate resources are needed to deliver these interventions.

The authors state that in developing countries treatment rates for people with mental health and substance abuse disorders is low, and that even in developed countries:

Treatment is typically provided years after the disorder begins.

The authors identify two roadblocks to improved care: stigma about these disorders; as well as inefficiencies in the distribution of funding and interventions.

Overall, the global burden of disease is moving away from communicable disease towards non-communicable diseases, and away from premature death towards chronic disabilities.

This trend has meant that mental and substance abuse disorders are becoming increasingly important contributors to overall disease burden, not just in developed countries, but worldwide.

We need to adjust our priorities in the delivery of care to reflect this.

Links

Whiteford HA et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet – 29 August 2013.

DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [Abstract]

Mental and substance use disorders are the leading cause of non-fatal illness worldwide: Data from the largest… http://t.co/yaAjiy22uy

@Mental_Elf must contribute quite highly to fatal disease too, especially in young people.

@markhoro summarises the findings on mental & substance use disorders from the #GBD Study 2010 in @TheLancet http://t.co/pk2JjiPA7k

All in the mind? http://t.co/ErOKztjXXn

RT @Mental_Elf: In case you missed it: Mental and substance use disorders are the leading cause of non-fatal illness worldwide http://t.co/…

MUST READ – Mental illness and addiction are the leading cause of non-fatal illness worldwide http://t.co/4YODtKkG6x

Mental & substance use disorders are leading cause of non-fatal illness worldwide http://t.co/BV3wvKVMIl via @sharethis

Mental Elf: Mental and substance use disorders are the leading cause of non-fatal illness worldwide http://t.co/CgwyEdkCkU

Investments 4 #mentalhealth!

Mental and substance use disorders are the leading cause of non-fatal illness worldwide http://t.co/1iT2TWZaRr

This is interesting: causes of death/mh diagnosis. Not sure laying claim to the “most deadly diagnosis” helps anyone http://t.co/X4lhUoLKeS

From @Mental_Elf Mental and substance use disorders are the leading cause of non-fatal illness worldwide http://t.co/STtHNA5eKm

[…] study spanning 187 countries, aptly titled the Global Burden of Disease Study (which we featured last year on the Mental Elf), found that between 1990 and 2010, there was an increase of 94,000 premature deaths secondary to […]