Bullying can be defined as an intentional and repeated negative behaviour towards another person, involving an imbalance of power that favours the perpetrator(s) (Olweus & Limber, 2018). Multiple studies have explored the characteristics and consequences of bullying: from assessments of the impact of bullying in children and adolescents (Ford, 2018), to its plausible role in mental health difficulties (Brugger, 2017), and its contribution to miscellaneous negative outcomes throughout the lifespan (Wolke & Lereya, 2015).

This degree of interest is more than justified given the widespread nature of this phenomenon: UK-based evidence suggests nearly 40% of young people have experienced bullying in the past 12 months (Brugger, 2017) and US data estimated 20.8% of 12 to 18 year olds were bullied at school (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016).

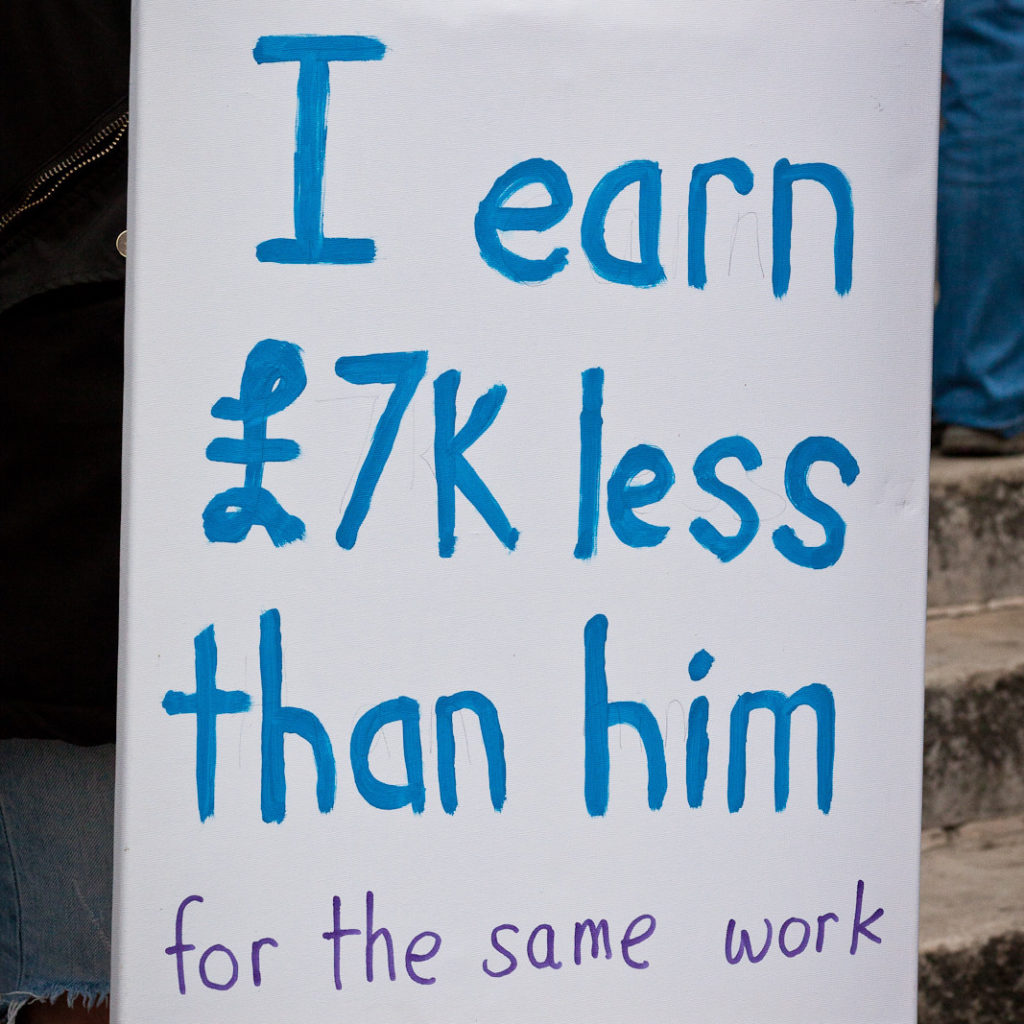

Despite this widespread interest, up until now, no paper had assessed the long-term economic consequences of childhood bullying. Brimblecombe and colleagues’ (2018) work attempts to estimate the most relevant economic consequences, at age 50, of having been bullied at age 7 and 11. To do so, the impact of bullying on individual factors (such as employment status, earnings, wealth) and on societal factors (e.g., health service use and employment costs) is explored and broken down according to gender, given relevant gender differences (ONS, 2016). Furthermore, possible childhood confounders (childhood IQ, emotional and behavioural problems, childhood adversity, and family social class) as well as adulthood covariates (partnership status, highest educational qualification and psychological distress) were incorporated into the analyses. The authors’ ultimate objective is to present ground-breaking evidence that contributes to further existing knowledge on the long-term implications of bullying.

UK-based evidence suggests nearly 40% of young people have experienced bullying in the past 12 months.

Methods

This paper uses the 1958 British birth cohort data to estimate the impact of bullying on multiple outcomes. This cohort’s strengths include a large study sample (n=4,702 women and n=4,540 men), extensive data coverage, and eight ages studied, with several objective measures and standardised scales. Nevertheless, it cannot be said to be representative of the ethnic diversity of the present day population (Power & Elliot, 2006).

The current study addresses a focused and pertinent issue. The fact that this cohort’s data included information about potential confounders allowed the authors to develop a more robust model, likewise benefitting from the participant’s prolonged follow-up.

Results

- In what concerns individual factors, after controlling for possible childhood confounders, the authors report that women who were frequently bullied during childhood had lower earnings and were more likely to have accumulated less wealth in the form of savings.

- As for men, they were found to be at greater risk of being unemployed, also having lower odds of owning a property.

- Regarding societal impact factors, being frequently bullied in childhood was found to be associated with higher employment related costs for men and higher health service related costs for women.

- However, the introduction of adulthood covariates into the model (recorded when participants were 33 years of age), helped explain several of the long-term economic impact variables at age 50, particularly for men.

- Only women’s greater likelihood to have accumulated less wealth and their higher health service related costs remained statistically significant once adulthood covariates were considered.

Women’s greater likelihood to have accumulated less wealth, and their higher health service related costs, were significantly linked to childhood bullying.

Conclusions

Brimblecombe and colleagues (2018) present evidence that being the subject of bullying during childhood may be associated with considerable and durable individual and societal economic impact, particularly for women.

The authors propose that the potential mediating role, during adulthood, of variables such as relationship status, psychological distress and educational qualifications, warrants the adoption of preventative measures that help diminish the long-term economic impact of bullying. Among these, additional social, relationship and mental health support, together with a better access to adult education, may go a long way to improving outcomes.

Bullying during childhood may be associated with considerable and durable individual and societal economic impact, particularly for women.

Strengths and limitations

This study uses a large and nationally representative cohort dataset, benefitting from a range of outcomes that were collected throughout the participants’ childhood, adolescence and adulthood, up until the age of 50. This enabled the authors to control for key childhood and adulthood confounders, thereby allowing for robust analyses that enable a more thorough understanding of the long-term economic consequences of bullying.

Despite this study’s strengths, some limitations bear mentioning. The adoption of 0.10 as a criterion for marginal significance was not explained. Furthermore, despite the inclusion of covariates as potential mediators, a mediation analysis was not sufficiently explored (e.g., PROCESS by Hayes, 2013) and no indirect effect sizes were reported.

Also, the use of self-report methods, known to be vulnerable to several biases (from recall to social desirability response biases) needs to be considered (the authors acknowledge this, discussing the potential for a recollection bias involving health service use).

This research may be susceptible to recall bias.

Taking #MHED2018 Beyond the Room!

Look out for live tweeting and podcasting from the #MHED2018 conference on 28-29 June 2018. This landmark conference brings together leading UK and international researchers, policy-makers, educators and allied professionals to explore the intersection between education and mental health and set the future research agenda for the field. The keynote speakers are Louise Arseneault, Mick Cooper, Natasha Devon, Celene Domitrovich, Kate Martin and Dan Olweus.

Read all the MHED2018 blogs that accompany this conference.

You can find out more about our #BeyondTheRoom social media service at beyondtheroom.net

Follow #MHED2018 on Twitter for the latest research, policy and practice relating to education and mental health.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Links

Primary paper

Brimblecombe N, Evans Lacko S, Knapp M, King D, Takizawa R, Maughan B, Arseneault L. (2018) Long term economic impact associated with childhood bullying victimisation. Social Science & Medicine, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.014

Other references

Bullying in childhood: cause or consequence of mental health problems? #AntiBullyingWeek

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression‐Based Approach. NY: The Guilford Press

National Center for Education Statistics (2016). Student Reports of Bullying: Results From the 2015 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey.

Power, C., & Elliott, J. (2006). Cohort profile: 1958 British birth cohort (National child development study). International Journal of Epidemiology, 35 (1), 34–41. DOI: 10.1093/ije/dyi183

Olweus, D. & Limber, S.P. (2018). Some problems with cyberbullying research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 139-143. DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.012

ONS (2016). Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings: 2016 Provisional Results. ONS, London.

Wolke, D. & Lereya, T. (2015). Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100, 879-885. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306667

Photo credits

- Photo by Tom Barrett on Unsplash

- Nick Efford CC BY 2.0

thank you for information