Promoting the mental health and wellbeing of university students is increasingly being recognised as valuable to create a “resilient generation” (Burstow, Newbigging, Tew, & Costello, 2018). This is spurred by the high levels of anxiety, depression, and loneliness being reported in university students globally (Arias-De la Torre et al., 2019; The Insight Network and Dig‐In, 2019; Xiao et al., 2017). Additionally, most mental health conditions develop by the age of 24 years, therefore making students an at-risk population (Kessler et al., 2010).

The time spent at university brings with itself a period of immense change, novel challenges, and significant transitions. The mental health of university students can be supported through several factors, e.g., cultivating meaningful social connections, developing self-regulatory and stress-management skills (Holdsworth, Turner, & Scott-Young, 2018). While a review by Fernandez et al. (2016) examined the structural and institutional strategies to promote the mental health of university students, this review by Nair & Otaki (2021) focuses on individual-level interventions “that aim to alleviate the burden of mental health challenges faced by the students and/or help them with coping mechanism that will foster their resilience.”

The promotion of individual level factors of university students can help them develop coping strategies to face the mental health challenges at university.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted on studies obtained from one database: PubMed. Only empirical quantitative studies in the English language were included (e.g., RCTs, pre-post studies, time-series, controlled trials without randomisation).

Studies were included if the interventions:

- Were conducted in a university setting

- targeted full-time university students

- evaluated the immediate or long-term impact on mental health

- included global measures of mental health and wellbeing

- involved a university counsellor,

The two authors screened and reviewed the studies, with any discrepancies discussed and reflected upon. The internal validity was assessed using the criteria by Jadad et al. (1996). The external validity was assessed using the criteria by Green & Glasgow (2006).

The authors performed a “qualitative meta-synthesis” using the framework of Braun and Clarke (2006) to “inductively build a general interpretation of all included studies, in alignment with the paradigm of constructivism.”

Results

The initial search led to 1399 records and 40 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Most of the included studies were from the Global North. Most were RCTs (n=25), quasi-experimental (n=5), cross-sectional (n=2), and pre-post studies without a control group (n=8) and so the internal validity was deemed to be “very high”. However, generalisability was limited considering that most of the interventions were based in only one institution in one country (with two exceptions). Thus, external validity was deemed by the authors to be “low/moderate.” The interventions were found to be “hybrid versions of existing evidence-based interventions” with a few “contextualised home-grown interventions.”

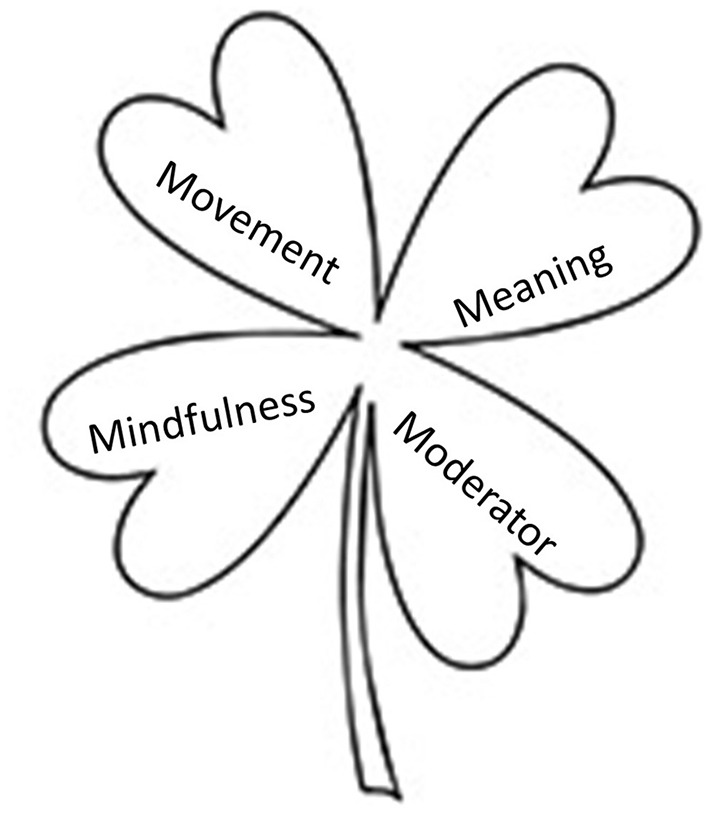

The authors inductively identified four overlapping categories from the included individual-level interventions:

- Mindfulness: These interventions used mindfulness as a technique to enhance self-awareness and reduce symptoms of stress and anxiety. The most popular (n=4) was Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction intervention that reduces stress and anxiety by targeting insight and concentration and relaxation. Other forms included Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to target cognitive reframing, psychological flexibility, and self-regulation.

- Movement: These interventions included a physical element or those which facilitated changes in sensation in the body. These were not limited to exercises, yoga, dance, aerobics, but also included sleep hygiene, behavioural activation, and a biofeedback intervention. Some of these interventions were peer-led (Byrom, 2018) and some delivered online (Puspitasari et al., 2017).

- Meaning: These included interventions that focused on connections and the ability for students to reappraise their cognitions, e.g., psychoeducation, curriculum-embedded approaches, and elective courses on stress reduction.

- Moderator: These interventions included an additional element of support that moderated the relationship between the student and the counsellor. For example, pet therapy and web-based/computer-delivered courses have been used to deliver psychotherapy to university students.

These 4 categories constituted the 4M-Model in which the 4Ms (i.e., mindfulness, movement, meaning, and moderator) were visually illustrated as a four-leaf clover.

The authors found that the most “commonly used approaches were mindfulness-based therapies, ACT, cognitive behaviour therapy, and psychoeducation.” 31 of the studies blended elements from the 4Ms listed above, suggesting that a blend of these elements can enhance the efficacy of these individual-level interventions.

A blend of the elements from mindfulness, meaning, movement, and moderator may enhance the effectiveness of the student mental health interventions.

Conclusions

The reviewers note that in the extant literature, there is “a lack of consensus on a common model/approach to effectively improve the mental health and wellness of university students.” In response to this, they propose the 4M Model of individual-level interventions for mental health promotion in university students. In this model, the blending of the 4Ms, namely mindfulness, movement, meaning, and moderator, can be effective in improving regulatory skills, cognitive functioning, emotional reactivity, and thereby reducing symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety.

A combination of key elements from mindfulness, movement, meaning, and moderator-based interventions may be an effective way of promoting mental health in university students.

Strengths and limitations

The systematic review included a range of interventions, most being studied in RCTs (randomised controlled trials). These short-term interventions were determined to be effective. Embedding the interventions within the curriculum is suggested to be an innovative way to address issues related to stigma and help-seeking. The qualitative meta-synthesis led to the development of a novel model, the 4M model of individual-level interventions, which highlights that the efficacious elements from wide-ranging interventions together can be a comprehensive way to promote mental health in university students.

The review itself does not provide details about the characteristics of the 40 papers, e.g., characteristics of the sample, delivery modes, length of the intervention, follow-up phase, choice of standardised outcomes and more. Each of these elements are important to assess the feasibility, effectiveness, contextualisation, and generalisability (heterogeneity) of the individual-level interventions.

The choice of one database also limits the range of studies included in the review and excluded grey literature, webpages, and qualitative and mixed-method studies. Furthermore, with most studies being from the Global North, it is important to note that the model proposed in this review is pertinent to a specific context.

While the 4M Model has been developed based on individual-level interventions, it is unclear whether these interventions measured positive mental health by evaluating a reduction in symptoms of poor mental health, or by promoting strengths, e.g., regulatory skills, social connections, subjective well-being, positive affect, among others. This is significant because positive mental health is not the absence of poor mental health (Becker, Glascoff, & Felts, 2010). Additionally, while some students might develop mental health conditions during university, all students will benefit from mental health promoting strategies that support their overall mental health and wellbeing. Therefore, further clarity is needed on whether these interventions reduced symptoms of poor mental health or whether they were strengths-based or a combination of the two.

Further information about the types of mental health promoting interventions included in this review is required.

Implications for practice

The review recommends a comprehensive biopsychosocial approach to develop and design interventions that include elements of mindfulness, movement, meaning, and moderators to provide holistic support to university students.

The review has attempted to categorise the key elements from effective individual-level interventions for university students. However, there is a further need for studies to contextualise the relevance of and elaborate upon the 4M Model in different contexts, population, and study designs.

A holistic and comprehensive approach to developing individual-level interventions can be effective in promoting the mental health of university students.

Statement of interests

No conflict of interest.

Tomorrow’s University: the future of student mental health & wellbeing

Going to university represents a major transition—and potentially a major challenge—in young people’s lives. Over the past few years it has increasingly been reported that university students are struggling with their mental health. However, research in this area is still in its infancy, so it is difficult to fully understand the scale of this issue and how to tackle it. Furthermore, institutions are struggling to offer adequate support, despite students being a population that is potentially easy for services to reach.

After a year of remote learning and a great deal of uncertainty over the coming months, how can we take meaningful steps towards improving students’ mental health and wellbeing?

Links

Primary paper

Nair, B., & Otaki, F. (2021). Promoting university students’ mental health: A systematic literature review introducing the 4M-model of individual-level interventions. Frontiers in Public Health, 9(June), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.699030

Other references

Arias-De la Torre, J., Fernández-Villa, T., Molina, A. J., Amezcua-Prieto, C., Mateos, R., Cancela, J. M., … Martín, V. (2019). Psychological distress, family support and employment status in first-year university students in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1209.

Becker, C. M., Glascoff, M. A., & Felts, W. M. (2010). Salutogenesis 30 years later: Where do we go from here? International Electronic Journal of Health Education, 13, 25–32.

Burstow, P., Newbigging, K., Tew, J., & Costello, B. (2018). Investing in a resilient generation: Keys to a mentally prosperous nation. Birmingham.

Byrom, N. C. (2018). An evaluation of a peer support intervention for student mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), 240–246.

Fernandez, A., Howse, E., Rubio-Valera, M., Thorncraft, K., Noone, J., Luu, X., … Salvador-Carulla, L. (2016). Setting-based interventions to promote mental health at the university: A systematic review. International Journal of Public Health, 61(7), 797–807.

Holdsworth, S., Turner, M., & Scott-Young, C. M. (2018). … Not drowning, waving. Resilience and university: A student perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 43(11), 1837–1853.

Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., … Williams, D. R. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 378–385.

Nair, B., & Otaki, F. (2021). Promoting university students’ mental health: A systematic literature review introducing the 4M-model of individual-level interventions. Frontiers in Public Health, 9(June), 1–10.

The Insight Network and Dig‐In. (2019). University student mental health survey 2018: A large scale study into the prevalence of student mental illness within UK universities.

Xiao, H., Carney, D. M., Youn, S. J., Janis, R. A., Castonguay, L. G., Hayes, J. A., & Locke, B. D. (2017). Are we in crisis? National mental health and treatment trends in college counseling centers. Psychological Services, 14(4), 407–415.

Photo credits

- Photo by Pang Yuhao on Unsplash

- Photo by Mikael Kristenson on Unsplash

- Photo by Nick on Unsplash

- Photo by Ana Municio on Unsplash

- Photo by Muhammad Rizwan on Unsplash