Bartkowiak-Théron and Asquith (2016) suggest that there has always been an overlap between models of law enforcement and public health. Police officers can have a key role to play in situations, in which, individuals are experiencing some sort of crisis related to mental health problems.

The Sainsbury Centre’s (2008) study suggested that up to 15% of incidents dealt with by the Police include some sort of mental health issue or concern. It also calls for the exercise of a range of skills. In his Independent Commission on Mental Health and Policing Report (PDF), that examined the response of the Metropolitan Police Service to mental health issues, Lord Adebowale (2013) described mental health issues as “core police business”. They may well be the emergency service that is first contacted by the relatives of those in acute distress, who are, for example, putting themselves or others at risk. If a person is acutely distressed in a public place then the likelihood of some form of police involvement is increased significantly.

There have been increasing concerns about the demands that mental health work places on police time and resources. In addition, police officers feel that they are ill-equipped to deal with mental health crises. In evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee, Sir Peter Fahy, then Chief Constable of Greater Manchester described mental health as the “number one” issue for his officers on the street.

Service-users and mental health professionals are concerned that the involvement of the police is not only stigmatising, it may well place individuals at risk. In her first speech as Prime Minister in 2016, Theresa May in moves to distance herself from David Cameron, highlighted a series of what she called “burning injustices”, these included the poor provision of mental health service – the PM stated “if you suffer from mental health problems, there’s not enough help to hand”. During her tenure as Home Secretary, May had been involved in two issues that have been examined in previous blogs – the use of police cells when people are detained under section 136 MHA and the number of prisoners with mental health problems. The police and other professionals who are not mental health clinicians are increasingly involved in responding to situations in which people are experiencing a mental health crisis.

One of the issues that is consistently raised in this area, is what sort of training should non-mental health professionals receive. A recent systematic review focuses on learning packages aimed at helping police officers and others who are in involved in the response to people in mental health crisis (Booth et al, 2017).

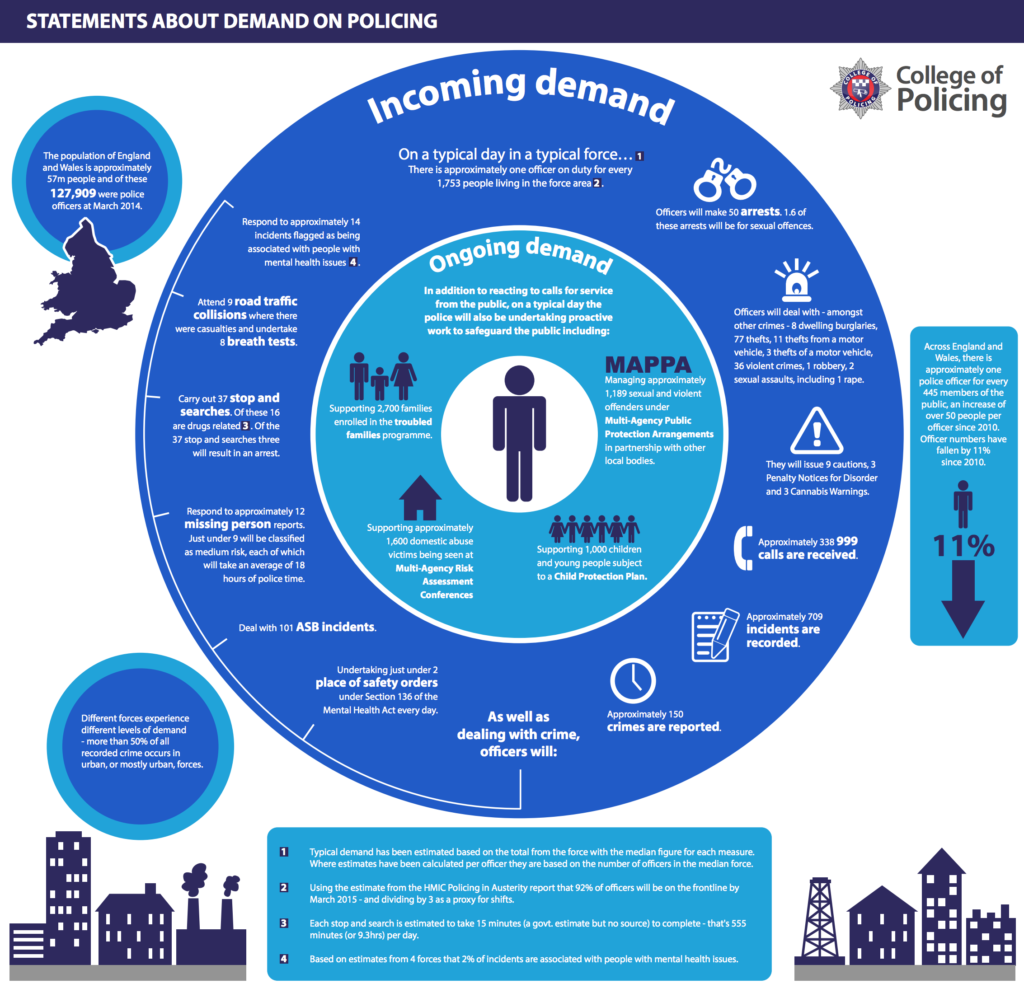

These issues have to be considered in the context of austerity which has seen significant reductions in services but also increased demands. This is a very significant issue for all public sector services.

The College of Policing infographic (PDF) places mental health work in the context of the other calls to the police.

Methods

The review is based on a database search from 1995 onwards. Studies that reported on the impact of training courses or learning packages aimed at police officers or others who “interact with the public in a similar way” to deal with mental health problems were included.

The primary outcomes that were considered were – “change in practice and change in outcomes for the groups of people came into contact with”. From 8,578 search results, 19 studies met the inclusion criteria: one systematic review, 12 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), three prospective non-RCTs and three non-comparative studies.

The training included broad mental health awareness approaches. The trainees included police officers, teachers and other public sector workers.

Results

The systematic review included in this review (Compton, 2008) focused on the Crisis Intervention Team model that originated in Memphis, following an incident where a man in mental health crisis was shot by the police. This programme provides selected officers with specialist training. These officers then provide a specialist frontline response. This review found that the CIT model has a positive impact on officers’ attitudes, belief and knowledge in the area of mental health. CIT officers also feel better prepared for dealing with calls that involve responding to a person in mental health crisis. The CIT may also be associated with a lower arrest rate. This is important as it means that individuals are not being drawn into the Criminal Justice System (CJS). This is positive in terms of those individuals as it means that they are more likely to gain access to appropriate mental health services. It also reduces CJS costs. This review failed to find support for the roll-out of the CIT model.

Herrington et al (2014) evaluated the Mental Health Intervention Team (MHIT) programme in Australia. The MHIT model is based on the CIT approach of specialist trained officers. This study reported no significant differences between MHIT and non-MHIT trained officers save for the fact that MHIT trained officers spent less time at MHA “events”: mean time 54.5 mins and control 99.5 mins.

There was a wide variety of other training programmes examined. These included 1 day mental awareness courses for frontline officers, as well as anti-stigma training, parts of which were delivered by people with experience of mental health problems. These approaches seem to have the greatest impact in explaining some of the “jargon of mental health” but also in tackling some of the myths in this area. These training approaches also open up opportunities for dialogue between not only those from the various professions but also most importantly service users.

The authors note that there are difficulties in assessing the outcomes of these training packages, partly because of the collection of the data but also because of a lack of agreement on what should be measured. A general conclusion was that training had a positive short term impact on those who attended, particularly in challenging stigma. However, the long term impact was much less significant. However, the few studies that examined the impact of training in terms of outcomes for service users found it had little or no impact. The authors note that there are logistical and ethical issues that make such studies problematic. However, it is a huge gap in research that is reflected across mental health services – there is a paucity of research into the experiences of service users when the MHA or other crisis interventions are used.

The training interventions featured in this review included broad mental health awareness training and packages addressing a variety of specific mental health issues or conditions.

Discussion

The famous criminologist Egon Bittner once described the role of the police officer as “Florence Nightingale in pursuit of Willie Sutton” (a legendary bank robber). This review confirms that the police have a key (perhaps unwelcome for some) role in mental health services, particularly in responding to those in crisis. There is therefore a need for officers to have appropriate training and an understanding of the legal position, but also local mental health services. In this training, it is important that service users have a central role.

There is a fundamental question that is not explicitly considered here: what should be the nature of that training? Police officers are not mental health professionals or psychiatric nurses; this raises the question as to what sort of training is most appropriate. If we start from the position that mental health is a key part of police work, the approaches that challenge stigma and debunk jargon probably have the greatest impact. More specialist training such as the CIT model is a separate consideration, more akin to the recent discussion here about street triage.

The review also emphasises that there is little if any research that examines the potential long-term impact of police involvement in mental health crisis from the perspectives of service-users. These are vitally important issues. The current pressures on mental health services mean that police involvement is likely to increase rather than decrease.

Research evaluating mental health training for UK police officers is urgently needed.

Links

Primary paper

Booth A, Scantlebury A, Hughes-Morley A, Mitchell N, Wright K, Scott W, McDaid C. (2017) Mental health training programmes for non-mental health trained professionals coming into contact with people with mental ill health: a systematic review of effectiveness. BMC Psychiatry 2017 17: 196 DOI: 10.1186/s12888-017-1356-5 https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-017-1356-5

Other references

Bartkowiak-Théron, I and Asquith, NL (2016), Conceptual divides and practice synergies in law enforcement and public health: Some lessons from policing vulnerability in Australia, Policing & Society. DOI: 10.1080/10439463.2016.1216553.

Compton MT, et al. (2008) A comprehensive review of extant research on crisis intervention team (CIT) programs. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(1):47–55. [PubMed abstract]

Herrington V, Pope R. (2014) The impact of police training in mental health: an example from Australia. Polic Soc. 2014;24(5):501–22. [Abstract]

Bittner, E. (1970) Functions of the Police in Modern Society. Washington DC NIMH