When Jasna Russo’s paper ‘Through the eyes of the observed: re-directing the research on psychiatric drugs’ appeared in my inbox, I was and still am recovering from a fairly serious episode of madness and distress. Among other things, this involved referral to a psychiatrist and a review and change in medication. Yes I take medication.

For about two or three months I haven’t been able to think, read or write properly, and this is my first concerted attempt to do. With all this in mind, my reactions to Russo’s paper have been influenced by my most recent experiences. I was particularly struck and moved by one of Russo’s conclusions that:

what is needed is a profound, ongoing collective learning process about how to accept madness and distress as part of our lives, how to keep looking at what they mean and where they come from and how to alter our relationships in order to support each other through the necessary changes that these experiences are obviously calling for.

So this blog is both a personal reflection and critical commentary on Russo’s work. A separate blog by Alison Faulkner summarises Jasna Russo’s new paper and places it into current UK mental health context: How should we redirect research on psychiatric drugs?

Psychiatry, the psy disciplines and the (re)search for A Cure

Just before I lost it, I gave a lecture for the South London CLARHC at King’s College London on patient and public involvement (PPI) in research. I argued that PPI must play a central role in research governance and ethics, as history shows that research ethics exist because the doctor-patient power relationship in research can be very harmful. As Russo explains, in drug trials, we still have “experts on the one side and passive research subjects on the other.”

I agree with her that we cannot allow PPI to continue as “a form of busywork in which the politics of social movements are entirely displaced”. Russo’s focus is on ‘omnipresent’ psychiatric treatment here. However, I would argue that her critical ideas can potentially transfer from psychiatric drug trials to all mental health research; including clinical psychology and other so-called ‘psy disciplines’ (McAvoy, 2014). As service users and survivors we can become caged in explanatory psychological frameworks or morally slurred with labels as much we can get trapped in psychiatric paradigms, drugged up, unable to communicate our distress on our own terms.

By chance I ended up drifting down the psychiatric and medication path, but it could easily have been clinical psychology path. I may display traits signifying psychological disorder or symptoms indicating a psychiatric diagnosis (or three), but I’m still a sick, broken, abnormal thing, in need of fixing by drugs, behaviour modification or therapy or though professionalised gifts of ‘care’. According to Russo, at scale, this can result in:

The systemic neglect of people’s potentials, aspirations and dreams when making judgments about the quality of their lives [and this] is particularly unfair.

Yes, if the writer Virginia Woolf had been medicated, she might not have put rocks in her pockets and walked into the River Ouse to die, but that Virginia Woolf may not have written what and how she did. On lithium would she have just been a posh lady going shopping and having a dinner party in Kensington, rather than Mrs Dalloway contemplating the mystery and purity of a shell-shocked man killing himself? If she had submitted to psychotherapy to resolve her bisexuality or feminist non-conformity, would she have written Orlando?

I believe Russo is right that, whatever we end up doing or taking to relieve our pain and distress, reductionist clinical models should not be the only option and we must have freedom from the legal compulsion to have treatment.

We should have the right to make a fully informed choices about taking medication or not because it can affect our very selves. Because we know so little, nearly all so-called evidence-based drug and other interventions end up being individual experiments, with harms and benefits. ‘Treatment’ is therefore an ethical and human rights issue beyond the scope of ‘mental health’, as the author argues.

Experiential knowledge of psychiatric drugs

To have fully informed choice we should be able to seek the advice of those who have had the treatment themselves, not just those who have researched and prescribed them:

Perhaps this can be likened to the difference between a visitor to a foreign country reading a tourist guidebook, and actually speaking with people who live there (Carr, 2009).

As the big mental health charity campaigns like to remind us, ‘we all have mental health’. Of course we do, but only a number of people are subject to compulsory treatment under the law; all secondary mental health services operate in a coercive environment, whether you are sectioned or not. Only a few people end up having almost every emotional reaction pathologised by others, and even by themselves. Only a few end up not knowing if it’s them or the drugs. I am one of those.

For good or ill, medication and, other psy interventions, “these substances do not only affect our bodies and minds – they enter our lives and shape our biographies”. I am with Russo when she argues this, and that we need to know more about the existential and ontological aspects of madness and distress and the treatments and interventions offered, partly because:

The latest survivor-controlled study on withdrawal reports that the reason that almost half of the participants (48%) decided to discontinue psychiatric medication was ‘I WANTED TO KNOW WHO I AM’ (caps mine)

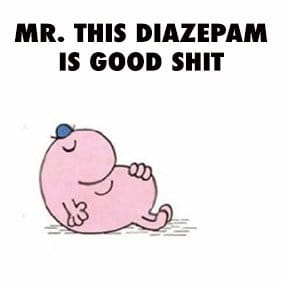

I’ve thrown medication away and been non-complaint because I no longer knew who I was or couldn’t stand the side effects (Carr, 2007). In a recent response to a friend seeking some first-hand experiential advice on medication, I listed the good and bad effects of six different antidepressants, two types of mood stabiliser, one type of anti-anxiety drug, two different antipsychotics and one major tranquilliser. One of these, I told her, I threw in a bin and took street drugs instead, another I discontinued because I was unconscious for most of the time, while one I stopped because it had no effect except for considerable weight gain, but one I love because it is, essentially, a mental painkiller.

Credit: Dolly Sen, @dozzyangel, dollysentraining.com

The medication I’ve just been prescribed I know little about. But looking to the research blogs here, I discover that research still hasn’t told us how or if aripiprazole (Abilify) works. So I turned to someone who had taken it…

From assessing people to re-thinking treatment

Whether research or PPI participants, or service users and patients, we are situated in various psy disciplines with power dynamics that can alienate us from each other, ourselves and our experiences. Mental health systems so often stand in the way of us developing our own ‘strategies for living’ with madness and distress (Faulkner & Layzell, 2000); building the kinship between who feel set apart from the world and the coming together of the great diaspora of the traumatised and haunted who have the potential to support and protect one another. No one knows more about surviving than survivors, so how do we play a leading role in re-thinking treatment?

the central and most pressing question for services is how to approach these experiences at all, if not with medication. This is an immense question and at the same time, an area where the knowledge of people who ‘reached the other side’ and their support has a unique and leading role to play.

In a highly fragmented, post-modern age, clinicians from various scientific disciplines in mental health still seem to be searching for a grand unifying theory and cure for whatever ails us, yet we still don’t really know what ails us (Bhugra et al., 2017; Carr, 2017, Rose, 2018). Russo makes a very important assertion about the future of psychiatry and all mental health disciplines here:

If our societies are ever to treat madness and distress with respect and dignity and seek to understand and accommodate rather than control and eliminate – then we need to admit that we don’t know how to do that… (bold mine)

![Credit: Nick Lloyd, @photographs_etc [with apologies with Barbara Kruger])](https://www.nationalelfservice.net/cms/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/image2.jpeg)

Credit: Nick Lloyd, @photographs_etc [with apologies to Barbara Kruger].

Pure ideological debates tend to omit complex truths and struggles of those who take or do not take these substances.

This brings us back again to the persistent argument from service users, survivors, their organisations and communities, and echoed in this paper, that we must have independent organisations, arenas and power bases from which to think and do for ourselves (Ormerod, 2018).

Conclusion

Russo’s paper is a very rare example of independent survivor scholarship, undetermined by the interests of those whose careers depend on us being ‘treated’, however well meaning they are. She speaks with one of the most marginalised voices of all, from a community where words can be difficult to use, and many are used to living with emotional and psychological pain in shame and silence.

One of the key messages from Russo, is that if we are to find ways of asserting ourselves in psychiatric and other research and treatment agendas we need to find and use our own words because:

…searching for the right words is at the core of our infinite journey towards understanding our world and the world we live in.

Her paper is valuable and vital because she does not platform a stance, but opens up questions. She compels us to be aware of the limitations of the questions being asked, and our answers – be it in research or more generally. Do the questions asked in mental health research still require answers articulated in relation to symptoms and treatment?

How are you OR what are your symptoms OR are you better yet?

To me, Russo says question even the questions, and think hard about the answers. So, to end, here are some fantasy answers to the ‘how are you?’ questions I’ve had from various people over the past month or so, which seem to encapsulate the necessary difficulty of finding the right words, even if they stay in your head.

Psychiatrist: How are you? (Translation: What are your symptoms?)

I’ve got constant violent and bloody intrusive thoughts. I’m suicidal and it’s so hard to resist harming myself again. When things get really bad, I end up on the bathroom floor with an angry male in my head was telling me ‘why don’t you shoot yourself in the face?’ I curl up in a ball and I cry and moan until it stops. Then I get up and have a large drink.

Work: How are you? (Translation: Are you better yet?)

I’m working but malfunctioning. Yep. Fine. Getting by. I can’t sleep or concentrate. I’m coasting along on vaping, vodka and Valium. My mind is not entirely my own, and at least once a day I think about killing myself. But yeah, I’m feeling better, I guess. I’ll be on it soon. I’ll email tomorrow. Sorry for the delay.

Me: How are you?

I am both dead and alive. My head is filled with uncontrollable violence; it is filled with clay crawling with worms. My stomach is filled with utter dread. My heart is filled with overwhelming love and immobilising sorrow. And then suddenly everything is a hollow nothing.

Links

Primary paper

Russo J. (2018) Through the eyes of the observed: re-directing research on psychiatric drugs (PDF). McPin Foundation, Talking Point Papers 3, Edition 1, June 2018.

Other references

Faulkner, A., & Layzell, S. (2000) Strategies for Living: A Report of User-Led Research into People’s Strategies for Living with Mental Distress (PDF). London: Mental Health Foundation.

Rose, N. (2018) Our Psychiatric Future London: Polity Press

Bhugra, D. et al, (2017) The WPA-Lancet Psychiatry Commission on the Future of psychiatry. The Lancet Psychiatry Vol 4 October 2017 pp.775–818.

Carr, S. (2017) Renegotiating the contract. Lancet Psychiatry Vol 4 October 2017 pp. 740-741 [Abstract]

Carr, S. (2009) The Sick and the Well? In: Sweeney, A. et al (eds.) This is Survivor Research Hay-on-Wye: PCCS Books

Carr, S. (2007) What Helps Me if I Go Mad? The Cinema Cure In: Peter Stastny/Peter Lehmann (eds.) Alternatives Beyond Psychiatry Berlin: Peter Lehmann Publishing pp. 54-55

Ormerod, E. et al. (2018) SRN Manifesto. Survivor Researcher Network – Mental health knowledge build by service users and survivors (PDF). London: National Survivor User Network (add link)

McAvoy, J. (2014) Psy disciplines In: Teo, T. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology New York: Springer pp. 1527-1529.

[…] Read more: https://www.nationalelfservice.net/populations-and-settings/service-user-involvement/where-i-end-and… […]

Thank you for this Sarah – it’s a really brave and insightful piece of writing. I find straddling the patient / professional domain hard, and whilst I draw on my own experience, I’m always acutely aware that my story is just one, and other people’s are different. But I think we do need to remember, that the only expert in ourselves, is ourselves… and the many questions you raise here about what does well even look like, what should we be striving for, and who should determine that are all good ones… I think I leave with more questions than answers, but they are good questions… Thank you!