Citizen science can be defined as ‘public engagement in scientific research activities where citizens actively contribute to science either with their intellectual effort, surrounding knowledge, or their tools and resources’ (Socientize Consortium, 2013). Citizen science therefore promotes widespread public engagement across various crucial phases of the research cycle, encompassing conceptualisation, data collection, knowledge translation, and evaluation (Katapally, 2019; Silvertown, 2009). However, whilst this methodology has gained popularity in the sciences, there is little guidance on how to use this approach within the field of mental health research.

Todowede and colleagues (2023) therefore conducted a systematic review to:

- Investigate the views of researchers and citizen science contributors regarding the use of citizen science projects in mental health in relation to the ten principles of best practice guidelines for the application of citizen science (Robinson et al., 2018)

- Identify the ethical and legal issues arising from citizen science approaches in mental health research

- Integrate the findings to develop best practice guidelines for future citizen science projects in mental health

Citizen science is the involvement of large public populations in research, including at the stages of data collection and knowledge translation.

Methods

This review used a comprehensive search strategy spanning both peer-reviewed academic literature and grey literature. Several sources were searched including multi-disciplinary academic databases, websites and blogs, conference proceedings, individual journal searches and citation tracking.

Inclusion criteria were documents reporting on:

- Citizen science as a research approach to engage public contributors in any form of mental health-related research;

- Citizen science studies that engaged mental health stakeholders, especially people with lived experience of mental health issues;

- The experience of conducting or participating in a citizen science project that is related to mental health;

- The use of citizen science approaches to collect data using any form of study design.

Documents were excluded if they reported on:

- The use of other predefined participatory research methods (e.g., co-design, coproduction or surveys and interviews to involve defined community or study participants);

- Studies using citizen science that were not focussed on mental health.

Screening and data extraction were conducted by at least two authors. A quality assessment of included articles was not performed, due to the inclusion of a broad range of document types which rendered traditional quality assessment tools infeasible.

A deductive thematic analysis was performed using the ten European citizen science association principles (Robinson et al., 2018) as an initial framework.

In line with citizen science frameworks, the review team included a mixture of researchers and non-scientist representatives, including some individuals with lived experience of mental health problems or mental health distress.

Results

This review incorporates 9 articles across various study designs, all carried out in high-income countries. Apart from the clinical population, there was no discernible trend regarding the participants involved in citizen science. Additionally, none of the studies included in the review adhered to any reporting guidelines.

- Involvement: Citizens were most commonly involved as contributors providing or collecting data or completing tasks for the research project.

- Genuine science outcome: All included projects achieved the goal of a genuine scientific outcome; 6 out of 9 studies used citizen science to investigate primary mental health research.

- Benefits: Both citizen and professional scientists recognised multiple benefits. Citizen scientists saw improvements in empowerment, information, social support, personal enjoyment, mental health, and quality of life, while professionals noted its inclusive and efficient research approach, echoing the perceived benefits for citizen scientists.

- Stages of participation: Most citizen scientists participated in data collection and analysis of data collected by professional scientists. A few studies involved citizen scientists in the creation of the study and dissemination of results.

- Feedback: Most studies did not report any aspect of feedback.

- Research approach: The included studies recognised the limitations of citizen science, including biases in task instructions affecting outcomes, unpredictable participant engagement and the need for quality relationships supporting mental health. Challenges included distressing messages posted by participants, requiring dedicated platform moderation.

- Data availability: None of the included studies reported public availability of their data, and 7/9 studies were published in an open access journal.

- Acknowledgement: Just over half of the included studies acknowledged their citizen scientists by thanking them for their participation as an unspecified group (e.g., not by name).

- Evaluation: All studies in the review generated a scientific output. Data quality was achieved through diverse participation and project-specific training as well as strategies to prevent data contamination between participant groups. High dropout rates of citizen scientists were reported. Barriers to engagement included time constraints and commitments, technical challenges and personal factors.

- Ethical and legal issues: Three ethical issues were identified: security, personal information and safeguarding issues. Two studies reported having obtained ethical approval prior to commencement of the research, and three reported obtaining informed consent from citizen scientists.

Both citizen and professional scientists recognised the benefits of citizen science, which included improvements in mental health and quality of life.

Conclusions

It is telling that this systematic review only managed to identify 9 eligible studies. Despite this review finding clear benefits of citizen science, there is more that can be done to encourage it’s use within mental health research.

Few studies were included in this review; we need to do more to encourage the inclusion of good quality citizen science within mental health research.

Strengths and limitations

The authors should be commended for their inclusion of a varied and diverse research team, encompassing both citizen and professional scientists, and specifically including lived experience of mental health. Given the qualitative nature of this evidence synthesis, it would have been good to see a reflexivity statement to explore how these diverse characteristics may have impacted on the way in which knowledge was experienced or interpreted.

The authors should also be commended for their rigour in conduct of this review. The search strategy is impressively comprehensive, and great care has been taken at each stage to ensure rigour. Transparently reporting this process also acknowledges the significance of open science.

Whilst clear reasons were given for not performing a quality assessment, it is a shame that this is missing from this important review. Given that the information from included studies was used to create best practice guidelines (see Implications for practice), it would be good to know what the quality of the evidence was that has been used to inform these.

This review is rigorously conducted, though suffers from a lack of quality assessment which makes it difficult to determine how reliable the findings are.

Implications for practice

The authors use their qualitative synthesis to create best practice guidelines for conducting and reporting mental health citizen science research. Building upon the ten European citizen science association principles, the authors give additional information regarding mental health-specific considerations:

1. Involvement

- Citizen scientists should include people with lived experience of mental health issues in roles such as contributor, collaborator, and project leader.

2. Genuine science outcome

- Involve key stakeholders to ensure that research leads to change.

3. Benefits

- Identify planned benefits from the outset.

- For citizen scientists, participation is not the norm, though more active roles should be reimbursed.

4. Stages of participation

- Participation at all stages of the project should be encouraged by researchers.

5. Feedback

- Plan and build-in a co-developed feedback approach from the start to inform citizen scientists about: a) key findings, and b) use of findings.

6. Research approach

- Consideration should be given to safeguarding issues to protect people with lived experience of mental health.

7. Public data availability

- Early co-creation of a data management plan with contributors is important.

- Ensure data protection legislation and relevant local information governance policies are followed.

- Open-access publication is the norm.

8. Acknowledgement

- Any presentation of findings should acknowledge: i) all contributing citizen scientists as an unnamed group, ii) with their permission, individual named contributors, and iii) with their permission, named representative groups.

9. Evaluation

- This should cover scientific outputs, data quality, participant experience, researcher experience and wider society/policy impact.

10. Legal and ethical

- If no personal information is collected, there is no need to obtain informed consent.

- Where personal information is collected, it is important to obtain informed consent.

- Technology security and anonymisation should be addressed.

- A collection of IP addresses or moderation of contributions should be explicit.

- Debriefing and training should be provided.

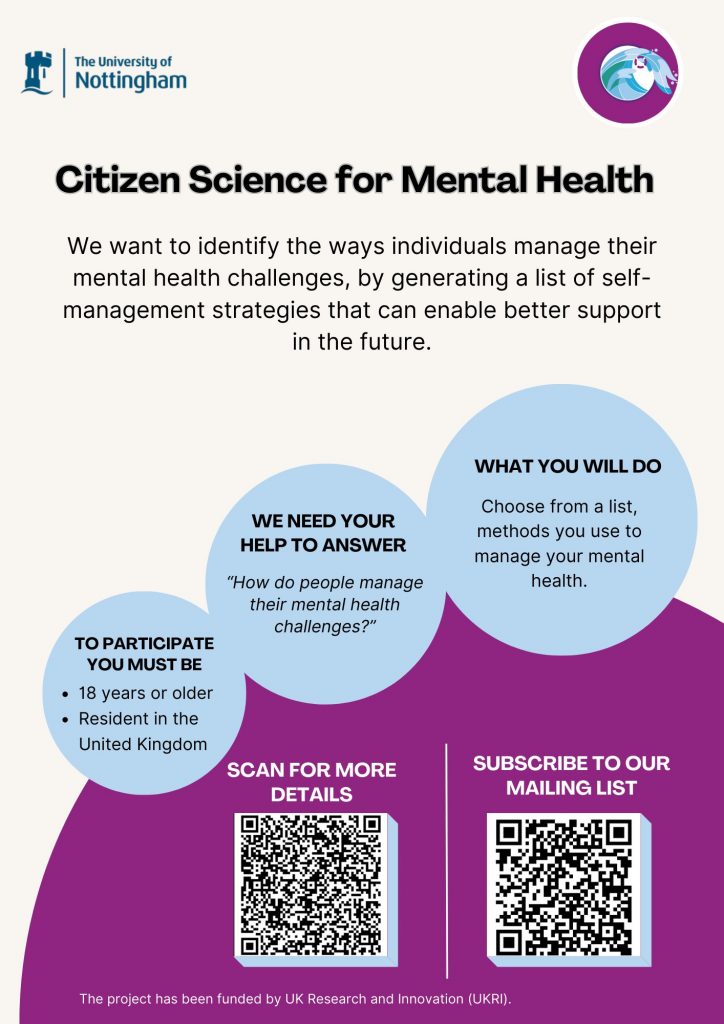

If you are a budding citizen scientist and you’re keen to get involved in mental health research, check out this study based at the University of Nottingham:

Citizen Science for Mental Health. Click here to find out more.

Statement of interests

No competing interests.

Links

Primary paper

Todowede, O., Lewandowski, F., Kotera, Y., Ashmore, A., Rennick-Egglestone, S., Boyd, D., … & Slade, M. (2023). Best practice guidelines for citizen science in mental health research: systematic review and evidence synthesis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14.

Other references

Katapally, T. R. (2019). The SMART framework: Integration of citizen science, community-based participatory research, and systems science for population health science in the digital age. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(8), e14056.

Robinson, L. D., Cawthray, J. L., West, S. E., Bonn, A., & Ansine, J. (2018). Ten principles of citizen science. In S. Hecker, M. Haklay, A. Bowser, Z. Makuch, J. Vogel, & A. Bonn (Eds.), Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy. UCL Press (pp. 27-40).

Silvertown, J. (2009). A new dawn for citizen science. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24(9), 467-471.

Socientize Consortium (2013). Citizen science for Europe. Towards a better Society of Empowered Citizens and Enhanced Research. Zaragoza, Spain: SOCIENTIZE Consortium.

Photo credits

- Photo by Hannah Busing on Unsplash

- Photo by Vlad Tchompalov on Unsplash

- Photo by Lesly Juarez on Unsplash

- Photo by MIGUEL GASCOJ on Unsplash

- Photo by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash

- Photo by Riccardo Annandale on Unsplash