The role of the ‘patient’ in health and social care research has been advocated for over twenty years (Goodare & Smith, 1995). INVOLVE define patient and public involvement (PPI) as “doing research ‘with’ or ‘by’ people who use services rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them.” (Hanley et al., 2004).

There are three main arguments for involving people with lived experience in the research cycle:

- First, an epistemological argument which suggests that people with lived experience of the phenomena being studied may bring specific knowledge and experiential insights otherwise unavailable to the researcher (Boote, Telford & Cooper, 2002)

- Secondly, a moral argument that, as UK taxpayers, the public should be actively involved in any publicly funded research which may affect their health status or the functioning of the NHS (Thompson et al., 2009)

- Finally, there is a consequentialist argument which suggests that involving service users in the research process can lead to positive outcomes such as higher quality research as well as patient and public contributors learning new skills and gaining confidence.

Despite the associated benefits of involving patients and the public in research, those who are conducting research as part of doctoral studies (e.g. in pursuit of a PhD), may face significant challenges to successfully involving patients and the public in their research. Chief among these barriers is a lack of funding – indeed, some doctoral research is unfunded altogether, leaving no budget for involving patients and the public. In addition to this, the timescales of doctoral research can present challenges to involving patients and the public, often making it impossible for contributors to be involved in the very early or subsequent phases of doctoral research.

The present paper (2020) therefore aims to present patient and public involvement approaches taken in two doctoral studies and outlines how this impacted the processes and outcomes. The paper also suggests how future doctoral researchers can meaningfully involve patients and the public with limited resources.

Doctoral researchers may struggle to involve patients and the public meaningfully in their research due to limited time and funding.

Methods

Study one

The goals of PPI, which aimed to design an intervention to improve outcomes of overweight adults were to:

- Obtain feedback on the appropriateness of overall PhD research questions and aims

- Check readability and suitability of data collection tools throughout the study

- Finalise an intervention booklet design, checking appropriateness of content and usability.

To meet the first two of these aims, one contributor was contacted at various points throughout the doctoral research study and asked to provide electronic (e-mail, telephone) feedback on documents such as protocols and topic guides. To meet the third aim, a meeting was held with a service user group and separately with a staff group to gather feedback on the first draft of the intervention booklet. Each group was asked to give informal feedback, with researchers using open prompts relating to usability and suggestions for improvements.

Study two

The aims of PPI in study two, which aimed to explore an evidence-based intervention for family carers, were to:

- Obtain the perspectives of family carers on the implementation work and findings throughout

- Ensure implementation strategies and recommendations for future implementation work are acceptable to family carers, as ‘end-users’ of the booklet intervention.

To meet these aims two ‘research buddies’ were recruited to give their perspective throughout the project. The researcher had regular contact with the ‘research buddies’ both face-to-face and by telephone to discuss the study’s progress and gain their perspectives as former carers. The research buddies also contributed to data analysis workshops by providing their feedback on anonymised transcripts, to explore the meaning of the data to them as family carers.

Results

The authors identify a range of impacts that PPI had on the researcher, the contributors and the research itself.

First, the researchers felt they had gained skills and confidence; organising and leading PPI meetings and making changes following feedback was perceived to increase skills in organisation, communication, partnership building and use of lay language. They also valued the opportunity to gain insights from a carer perspective, which would not have been possible from supervisors or academic resources.

Second, contributors all evaluated their experiences positively with the majority stating they would be happy to be involved again. Contributors felt there were no barriers to being involved, and that they had a new appreciation of the work involved in research.

Third, the authors report improvements to the research process as a result of PPI. For instance, research documents were improved in terms of readability, topic guides were made more sensitive and the layout and content of intervention booklets was improved in terms of usability and appeal. Contributors also offered potential solutions when faced with recruitment issues and offered alternative explanations to themes identified in qualitative data.

The authors also highlight some challenges encountered in their pursuit of PPI:

- Involving PPI panel members only using phone and email may help to save time and money, but may have hindered rapport building

- The input of research buddies sometimes had to be limited due to resources and time constraints. This highlights the need to carefully manage expectations of contributors

- PPI was felt to be ‘student-led’ and probably would not have happened without funding and the researchers previous experience with PPI.

Patient and public involvement led to positive outcomes for the researchers, the contributors and the research itself, though some challenges were identified.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that it was possible to conduct PPI at a meaningful level with limited time and funding during doctoral research. They argue that to ensure that doctoral researchers are sufficiently experienced and qualified to become the next wave of leading researchers, it’s essential that PPI is an integral part of doctoral training.

In my own experience of trying to involve people with lived experience of being in prison during my doctoral research, a lot of what the authors report resonates with me. Particularly, I am struck by the sentiment that PPI felt ‘student-led’. My institution offers several training courses on PPI and is generally encouraging, but I still feel that I have had to ‘lead’ on PPI, and indeed sometimes fight for it to be an integral part of my PhD. This echoes the need for a cultural shift amongst institutions and funding bodies; to make PPI an integral part of doctoral research. This, of course, needs to be achieved through making more funding available for doctoral researchers to be able to meaningfully involve patients and the public in their research.

Institutions and funders should ensure that patient and public involvement is an integral part of doctoral research and should provide funding so this can happen.

Strengths and limitations

This paper gives a much-needed example of how patient and public involvement work can be conducted as part of doctoral research. The authors should be commended for adhering to the GRIPP2 guidelines (Staniszewska, Brett, Simera et al., 2017) for reporting patient and public involvement, which makes for a clear and replicable outline of the approach taken.

As acknowledged by the authors, both had access to a considerable set of resources to assist with PPI in their projects, such as access to training, funding and a pre-existing PPI panel based at their institution. Though welcomed, it is my understanding that this support is not the norm for doctoral researchers wishing to undertake PPI, and so it would be good to hear about the experiences of other doctoral researchers who may have differing perspectives and advice on how to conduct PPI.

It would be good to hear from other doctoral researchers about their experiences of involving patients and the public in research.

Implications for practice

The authors make several recommendations for doctoral researchers who want to meaningfully involve patients and the public in their research:

- Be clear on the aims of PPI to avoid tokenism

- Consider your resources

- Seek advice from someone with experience and knowledge of PPI

- Record and report the impact of involvement on the research

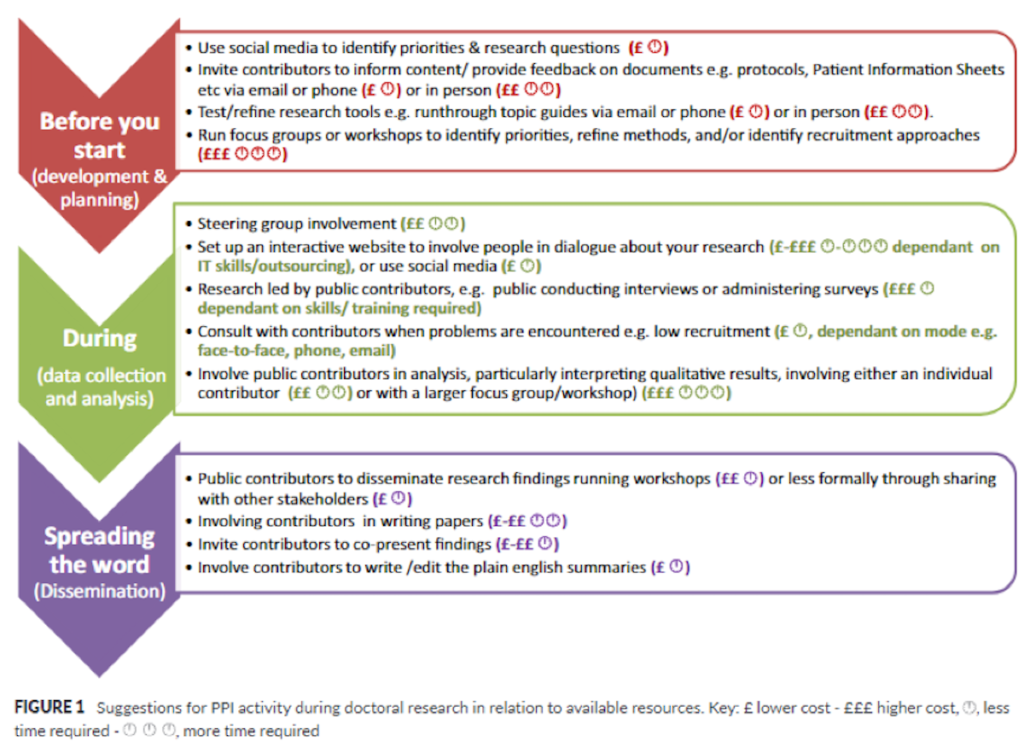

The authors also include a helpful figure which shows ways that doctoral researchers can involve patients and the public using the limited time and resources available to them. For instance, it’s suggested that doctoral researchers use technology to lower the time and costs of involvement activities.

The authors make several recommendations for how doctoral researchers can involve patients and the public in their research with the limited time and resources available to them.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

, . (2020) Patient and public involvement in doctoral research: Impact, resources and recommendations. Health Expect. 2020; 23: 125-136. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12976

Other references

Boote, J., Telford, R., & Cooper, C. (2002). Consumer involvement in health research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy, 61(2), 213–236.

Goodare, H., & Smith, R. (1995). The rights of patients in research. British Medical Journal Publishing Group.

Hanley, B., Bradburn, J., Barnes, M., Evans, C., Goodare, H., Kelson, M., … Wallcraft, J. (2004). Involving the public in NHS public health, and social care research: briefing notes for researchers. Involve.

Staniszewska, S., Brett, J., Simera, I., Seers, K., Mockford, C., Goodlad, S., Altman, D.G., Moher, D., Barber, R., Denegri, S. and Entwistle, A., 2017. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Research involvement and engagement, 3(1), p.13.

Thompson, J., Barber, R., Ward, P. R., Boote, J. D., Cooper, C. L., Armitage, C. J., & Jones, G. (2009). Health researchers’ attitudes towards public involvement in health research. Health Expectations, 12(2), 209–220.

Photo credits

- Photo by Wes Hicks on Unsplash

- Photo by Startaê Team on Unsplash