This report addresses service user and survivor views about ways of understanding madness and distress, but in particular about the potential of a social model.

Criticisms of a purely biomedical model for understanding mental illness (in which mental illness is assumed to exist as a disease with biomedical origins) have been around for some years now, dating at least as far back as the anti-psychiatry movement in the 1960s and 70s. Decades of research have failed to confirm biomedical explanations for mental illness (Bishop, 2014; Middleton, 2013; Thomas, 2013). However, the biomedical model appears to remain strong and well, dictating both the nature of our services and the research paradigm that dominates our evidence-based treatments (Faulkner, 2015).

Often absent from this debate are the voices of service users and survivors and this is where the strength of this report lies. In engaging with service users and survivors over a two-stage period, the authors have demonstrated that people living with mental distress are well able to enter the debate and engage with these complex issues.

People living with mental distress are well able to enter the debate and engage with complex issues.

Methods

This user-controlled study funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, was qualitative in its approach, using a combination of focus groups, interviews and an online survey. It is based on the findings from a previous study (Beresford, Nettle and Perring, 2009) plus further consultations with service users/survivors.

In this second stage, the aim was to reach a more diverse population of service users, including people from black and minority ethnic (BME) communities and older women. The findings from the first stage were checked out with participants and a few additional questions were asked, including about recovery and ideas for taking a social approach forward.

Results

It is hard to do justice to the fullness and complexity of the findings within such a small space. Although participants were strongly in favour of there being a wider recognition of social approaches to mental health, there were mixed views about the direct application of a social model of disability to mental health experiences:

- Some people felt that they could not describe themselves as ‘disabled’ or as having an impairment

- Most participants believed the medical model for understanding mental distress to be both damaging and unhelpful, and did not feel it helped their own understanding

- There was a strong view that the dominance of the medical model leads to a dominance of medical treatments in mental health services, neglecting the role and value of social supports

- People valued a more holistic approach which would take account of the whole person and their social circumstances, including the impact of such issues as racism.

Recovery also got a mixed reception. Many people felt that recovery is closely associated with a medical understanding of distress. Although some people had found the concept positive and helpful, there were also views that it had been co-opted by services and used as the basis for policies to cut services and reduce support.

Many of the issues and questions raised concerned the difficulties of achieving a shared language: people were unsure of the meaning of ‘social model’ and there were mixed uses and views of terms such as ‘mental illness’, ‘disability’ and ‘mental distress’. The study also asked people’s views about the term ‘madness’, which has recently re-entered the frame with the advent of the academic discipline ‘Mad Studies‘. Once again there were mixed views. Whilst some people were happy with the use of this term, many found it offensive and pejorative.

Another important theme was the complex relationship between medical and social understandings of mental distress, recovery and the welfare benefits system. People found these issues to be contradictory and unhelpful and some were highly critical of the current welfare reforms. On the one hand, services are encouraging people towards recovery, which often means less support and a goal of employment; whilst on the other hand, in order to claim benefits, it is necessary to emphasise personal deficits and vulnerabilities.

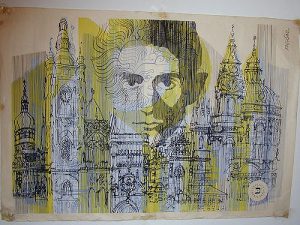

The current climate of austerity is fraught with tension and Kafkaesque contradictions for people living with mental health difficulties.

Conclusions

The main message from this project is the strength of people’s concerns about conventional medicalised understandings of distress and their belief in the value of social approaches. Recommendations from the report include the need to share the findings widely and stimulate more debate about these issues, for there to be more support and funding for such organisations as the Social Perspectives Network, and for mental health organisations to look more critically at their own adherence to a medicalised understanding of distress. The authors advocate ‘extensive and more sophisticated discussions’ about social approaches which fully and equally include mental health service users.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this report lies in the quality of the debate expressed. There are no easy answers to these questions, and the authors account for the complexity of the differing views with honesty and in a straightforward style. Service users and survivors are often invited into research to give their views about their personal experiences or about the services they have used, but rarely engaged in discussions of this nature. This is one of the gaps that user-controlled or survivor research is able to fill. The use of a mixed methods approach was probably beneficial to including a more varied range of people in the study.

I was initially critical about the number of quotations featured in the report compared to the analysis or explanatory text. However, I came to appreciate the value of hearing so many of these voices coming through, particularly given the complexity of the issues.

The report does not say how people were recruited to the study, which leaves the reader with some unanswered questions. Also the number of participants given in the text is 82 but the demographics in the appendix only account for 40. I think the difference is the number who filled in the online survey, but this is not made clear, and leaves one wondering why there are no demographics about survey participants. Finally, and unfortunately, the report is littered with typos which made it less than easy on the eye to read. This is such an unnecessary shortcoming that I find myself wondering about the process of production.

Summary

Overall, I feel that this report makes a major contribution to the mental health debate and I hope that many people will read it. I have to declare a personal interest here, as I am strongly in favour of social understandings of mental health and distress myself. It is a rare pleasure to read something that reflects my views so accurately. There is no shying away from the range and variety of views; that we will find no consensus about language does not surprise me. But it is indeed vital that we continue this debate. So many people come into mental health services as a result of trauma, abuse and discrimination.

I am as doubtful about the future of identifying a social model of mental distress as many of the people in this report, but I do think that we should keep on talking about how we can transform services to more adequately reflect people’s experiences and needs.

Let’s keep talking and listening to how we can transform services to more adequately reflect people’s experiences and needs.

Links

Primary paper

Beresford P, Perring R, Nettle M, Wallcraft J. (2016) From Mental Illness to a Social Model of Madness and Distress (PDF). London: Shaping Our Lives. www.shapingourlives.org.uk

Other references

Beresford P, Nettle M, Perring R. (2010) Towards a Social Model of Madness and Distress?: Exploring what service users say (PDF). York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Faulkner A. (2015) Randomised controlled trials: the straitjacket of mental health research? Talking Point Papers 1 (PDF). London: The McPin Foundation. [The Mental Elf blog of this report]

Middleton H. (2013) ‘Mental health service users’ experiences and epistemological fallacy’ Chapter Two in Staddon, (ed.) 2013. ‘Mental Health Service Users in Research’. Bristol: Policy Press.

Slade M, Priebe S. (2012) Conceptual Limitations of Randomised Controlled Trials. Chapter 10 in Priebe, S. and Slade, M. (2012) Evidence in Mental Health Care. London: Routledge.

Thomas P. (2013) Pinball Wizards and the Doomed Project of Psychiatric Diagnosis. Mad in America.

@Mental_Elf just what I was looking for, thanks

“On the one hand, services are encouraging people towards recovery, which often means less support and a goal of employment; whilst on the other hand, in order to claim benefits, it is necessary to emphasise personal deficits and vulnerabilities”

This is something that needs addressing. Our welfare and health and systems are working against each other – surely creating difficulty and inefficiencies. I often feel trapped by this conflict. Impossible to evidence disabilities to get support that you need when clinic letters and services typically focus on improvements and recovery.

Couldn’t agree more Bibi – thanks for sharing! Cheers, André

@Mental_Elf very interesting, thanks

RT @borromeannot: Good stuff @BeresfordPeter Thank you.A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/hmdomrmn0t h/t a…

RT @Mental_Elf: Great blog today from @AlisonF101

A social model for understanding madness & distress

https://t.co/2B4OG0F417 https://t.co/…

RT @Mental_Elf: New blog on @Solnetwork1 report on service user & survivor views about ways of understanding madness & distress https://t.c…

https://t.co/JKPh5xdymr… https://t.co/4wUbZfAQCY

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/61l8ddrfTY via @sharethis

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/vOGhnPcf7T via @sharethis. An interesting critique by @AlisonF101

@AlisonF101 on relationship between medical & social understandings of mental distress, recovery & welfare system https://t.co/2B4OG0F417

“people living with mental distress are well able to enter the debate and engage with these complex issues” https://t.co/9oSD2EO9R2

Don’t miss:

A social model for understanding madness and distress

https://t.co/2B4OG0F417 https://t.co/kb1tdiAlIs

#coventrymentalhealth social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/wZr5ebO4Q4 via @sharethis

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/cMp6GPrdrF via @sharethis

Service user and survivor views on ways of understanding madness and mental distress…. https://t.co/FMZKpSRpKN

RT @vaughanbell: A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/AisarnPXjG Great summary of an important report – via @…

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/SGbuHgXVwQ via @sharethis

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/UqWxWBbtMy via @sharethis @CEOWestVicPHN @ACMHN #recovery #consumers

RT @Mental_Elf: Today @AlisonF101 on recent report by @BeresfordPeter From mental illness to a social model of madness & distress https://t…

The voices of users & survivors highlight the contradictions of living w/ MH disabilities https://t.co/C01iZf1elr https://t.co/XfdNyq9tMo

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/59oFVFAyTm via @sharethis

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/2jVjtLrDGm via @sharethis – great blog with links to paper

Most popular blog this week?

@AlisonF101

A social model for understanding madness & distress

https://t.co/p3Bucg2gKA https://t.co/x53dhjIZv3

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/RGad5Rv59S

An interesting and worthwhile read … https://t.co/HY6ZmbLQnH

RT @DrWMB: helpful review of a research report on user & survivor views on social & medical models & recovery @AlisonF101 https://t.co/FgfD…

RT @niadla: A social model for understanding madness & distress https://t.co/T2zqF4gIwj TY @Mental_Elf @drmghisoni https://t.co/2yG1LxPAyt

Interesting paper – A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/4KvAgNV1VL via @sharethis

If interested in a non medical approach to mental health, I recommend this blog: https://t.co/xbi7vVGBxj

@Mental_Elf

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/AvbWk3GGqU via @AlisonF101

A social model for understanding madness and distress

https://t.co/uPkpEC2JdF https://t.co/vxKp6ycgjs

A social model for understanding madness and distress https://t.co/QphjLiyMIV via @sharethis

[…] Social models of madness and distress have been explored in an earlier blog by Alison Faulkner, and this paper adds another dimension to the blog discussion on research into the connections between trauma and psychotic symptoms. […]