Inpatient mental health services are meant to provide safe places for people experiencing mental health difficulties to receive support and recover, but for many, the reality is far from this ideal. Patients often report distressing experiences, including being subjected to restrictive practices like seclusion and restraint, coercion, and boredom. Far from aiding recovery, these experiences can compound trauma and make recovery more challenging. These are topics which have been covered extensively on the Mental Elf and cross the age ranges including children and young people’s inpatient services.

To improve inpatient mental health care, it’s crucial we fully understand patients’ negative experiences so that we can find ways to address them. Previous reviews have examined specific aspects of patients’ negative experiences, such as how they are impacted by surveillance technologies on wards or other risk management practices. Some have also focused specifically on the experiences of marginalised groups, such as black service users, who face systemic racism in care.

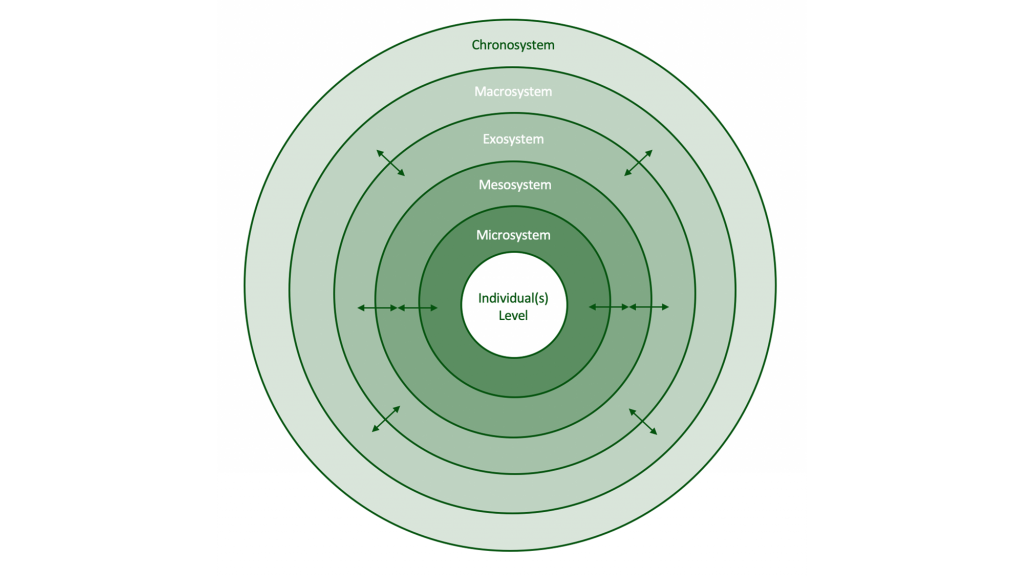

However, a recent qualitative systematic review by Hallett et al. (2024) is the first to take a broader approach, exploring the full range of patients’ adverse experiences in inpatient mental health settings. It goes one step further by applying Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (1992) to the findings, a theory which explains how a person’s experiences are shaped by multiple layers of their environment, from their immediate surroundings to wider societal factors.

By mapping how these layers influence adverse experiences in mental health wards, the review offers valuable insights that can guide improvements in service design and delivery, ultimately enhancing patient care and outcomes.

This was the first review to explore the full range of adverse inpatient experiences and the first to apply Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory.

Methods

The researchers systematically reviewed qualitative studies exploring patients’ adverse experiences in acute adult, forensic, and psychiatric intensive mental health inpatient care. They excluded specialist settings, such as inpatient services for children and young people, older adults, or people with learning disabilities.

They searched three academic databases and Google Scholar for relevant research. Data was extracted, checked, and studies were quality assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist.

The researchers used a “best-fit” framework to organise the qualitative findings in the included studies. They started with themes based on existing knowledge and refined them as new insights emerged during their analysis.

The team included a researcher with lived experience of inpatient mental health care who was involved in all stages of the review. The team also gathered feedback on preliminary themes from a Patient and Public Involvement group. This group, made up of five service users with varied experiences of acute and secure inpatient mental health care, helped shape the review’s findings, ensuring they reflected the real experiences of patients.

The team included a researcher with lived experience of inpatient mental health care and gathered feedback on preliminary themes from a Patient and Public Involvement group.

Results

111 papers were included in the review. These papers used a range of methodologies and were overall rated as good quality. The studies spanned the globe but were predominantly conducted in Europe (n = 80).

The review found a range of factors related to adverse inpatient experiences, suggesting that traumatic experiences in mental health inpatient settings can worsen outcomes. Adverse experiences were described under three main headings: the ecosystem, systems, and the individual.

The ecosystem

‘The ecosystem’ was described as the physical environment and available resources in which adverse experiences occur, and other people within or influential to that environment. Adverse experiences related to the physical environment and included factors such as poor ward conditions (e.g., sensory overlap such as loud noises and alarms going off), lack of activities leading to boredom, and feelings of wards being unsafe and like a prison due to blanket rules and observations. Factors related to interactions with others – usually ward staff, but also fellow patients and family members – also contributed to negative experiences. These included low staff numbers and the culture of poor visibility of staff in communal spaces, lack of information, exclusion from decision-making about one’s own care, and poor staff attitudes. These included stigmatisation and racism towards patients.

Systems

‘Systems’ were described as the formal processes of treatment including coercive management strategies (e.g., seclusion, restraint, threats of involuntary detention), the use of psychotropic medication, and the monitoring of progress through ward rounds. Such processes were felt to be punitive and induce fear among participants and were seen as intimidating and ineffective. Transitions (i.e. admission, transfer and discharge) were commonly associated with fear, whether they were voluntary or involuntary, due to the perceived coercion associated with these processes. This was particularly the case for admission processes involving police presence. For both admission and discharge transitions, poor communication and lack of involvement were viewed as contributing to negative experiences.

The individual

‘The individual’ was described as the infringements on autonomy and the (re)traumatisation that might be attributable to the totality of adverse experiences. Being on a ward often led to patients feeling a loss of control, privacy, freedom, power and choice, all of which created adverse experiences. These included lack of control or choice over admission or treatment choices, physical barriers such as locked doors, the lack of autonomy over everyday activities such as mealtimes and bedtimes, restrictions over the use of personal items, and the power imbalance felt between patients and staff. Patients reported feeling coerced and infantilised, with false choices rather than autonomy. Throughout the literature, patients described feeling traumatised by their experiences on inpatient wards, with factors such as gender, abuse, and racism contributing to this.

The review found a range of factors related to adverse inpatient experiences, suggesting that traumatic experiences in inpatient settings can worsen outcomes.

Conclusions

This review has shown that, on a global scale, adversity in inpatient mental health settings extends far beyond the harm caused by restrictive interventions. It highlights the complex interplay between systemic, environmental, and individual factors that contribute to these negative experiences. The review demonstrates that while the challenges are significant, the opportunities for improving mental health inpatient care are substantial.

Strengths and limitations

This review draws on a diverse range of studies from multiple countries, focusing on adverse inpatient experiences – addressing a key gap in the literature. It provides a valuable framework for mapping and addressing these negative experiences, offering practical insights for a wide range of stakeholders. The research benefitted from meaningful involvement of people with lived experience throughout the project, helping to ensure that the findings are grounded in real-world perspectives.

However, there are some limitations to consider. A large proportion of the included studies were conducted in Europe, and the authors only included studies published in English. This may limit how well the findings apply to other mental health systems. Certain settings, such as inpatient services for children and young people, individuals with learning disabilities, and older adults, were excluded, restricting the applicability of the findings to these groups.

While ecological systems theory provided a valuable and practical framework for interpreting the findings of this review, it has some limitations. The review did not examine in detail variations in findings across different settings and populations, such as countries, ward types, or patient demographics. As a result, whilst the framework presented is broadly applicable to inpatient mental health services in general, it may not fully account for the unique nuances of specific contexts and populations. Another limitation of the framework is that the boundaries between system levels can sometimes be unclear, and the relative influence of different layers may vary across cultural contexts and over time – aspects that could have been explored further in the paper.

The review authors note that few included studies explicitly examined adverse experiences, other than those on restrictive interventions, potentially leaving certain aspects of patients’ experiences underrepresented. Comprehensive investigation is further complicated by the absence of a consistent definition of “adverse experiences” in the literature, and varied approaches to studying and measuring them.

Research findings are shaped not only by how adverse experiences are conceptualised, but also by study designs, including data collection and analysis methods. Many of the included studies lacked transparency regarding the nature of interviewer-participant relationships, making it challenging for the reviewers to assess potential biases. And, while reviewers examined patient quotes in the original studies to try to mitigate selective reporting, such biases may persist. These limitations may have meant that patients’ experiences were not fully or accurately represented, especially given the lack of patient co-researchers in most studies.

Finally, the review’s focus on adverse experiences is both a strength, as it addresses an important but under-explored area, and a limitation, as it may unintentionally overlook the complexity and diversity of patients’ experiences in inpatient settings. Many people might have both negative and positive experiences, and what one person finds harmful could be helpful for someone else. A more balanced approach that considers both positive and negative experiences could provide a more complete understanding of inpatient care. Capturing the full range of patient experiences would highlight not just what causes harm, but also what supports recovery, further guiding improvements in inpatient.

Adverse experiences were not consistently defined across included studies and few of them explicitly examined adverse experiences.

Implications for practice

The framework developed from the findings of this review offers a tool for a wide range of stakeholders, from academics and clinicians to commissioners and policymakers, to better understand and address adverse experiences in inpatient mental health settings. It highlights the interconnectedness of individual, relational, and societal factors in inpatient care. By addressing the full spectrum of adverse experiences identified, mental health services can make strides towards environments that not only prevent harm but actively contribute to the wellbeing and recovery of individuals in their care.

The review’s emphasis on the role of systemic factors in shaping patients’ experiences is important because it challenges the common but problematic idea that recovery is mainly a matter of individual resilience. This point is driven home when the authors ask:

How can someone expect to recover, or at least improve to the point of discharge, when they are surrounded by an ecosystem, and the associated processes and transitions, that create adversity.

Recognising the impact of these broader contexts shifts the focus from expecting individuals to simply cope better, to addressing the structural changes to inpatient services needed to reduce harm.

Meaningful change in inpatient mental health care is likely to be complex, requiring consideration of diverse factors and perspectives. It is possible that some adverse experiences are inevitable in the current system, especially when patients’ rights are restricted, and there are probably no one-size-fits-all solutions. However, the findings of this review offer a valuable starting point for conversations between patients, carers, healthcare professionals, and policymakers to better understand how patients are impacted by inpatient care. These insights can help guide actions to reduce harm and improve care at all levels:

- at the individual level (e.g., by increasing patient choice, control, and freedom),

- within systems (e.g. by reducing coercive practices and improving admission/discharge procedures),

- in ecosystems (e.g. by improving physical ward environments and increasing patient involvement), and

- in broader policymaking (e.g. by shaping national policies and best practice guidelines).

Together, this could make inpatient care more inclusive, more centred on patient autonomy, and less traumatising; ultimately reducing harm and improving care across the system.

This review’s findings also highlight the importance of involving people with lived experience at every stage of future research – from developing research questions and designing studies to collecting and analysing data and sharing findings. Their involvement would help ensure research better reflects their priorities, perspectives, and experiences. It would also be valuable to work together with people who have experienced inpatient mental health care to create a more inclusive and standardised definition of “adverse experiences.” This could help future research take a more consistent and comprehensive approach to studying these experiences and exploring change over time.

Future research could also explore how the framework presented in this paper can be tailored to different contexts, such as varied ward types, geographic locations, and patient populations. Realist approaches could be used to further investigate the mechanisms underpinning the links between these factors and outcomes – examining what works (or doesn’t), for whom, in what circumstances, and why, to inform the development of tailored interventions. This would help stakeholders implement more effective, evidence-based strategies to prevent harm and promote positive outcomes across diverse inpatient settings and populations.

By addressing the full spectrum of adverse experiences, mental health services can make strides towards environments that not only prevent harm, but actively contribute to the wellbeing and recovery of individuals in their care.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Hallett, N., Dickinson, R., Eneje, E., & Dickens, G. L. (2024). Adverse mental health inpatient experiences: Qualitative systematic review of international literature. International journal of nursing studies, 161, 104923. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104923

Other references

Astrid Moell, Maria Smitmanis Lyle, Alexander Rozental, Niklas Långström, 2024 Rates and risk factors of coercive measure use in inpatient child and adolescent mental health services: a systematic review and narrative synthesis, The Lancet Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(24)00204-9.

Griffiths, J. L., Saunders, K. R. K., Foye, U., Greenburgh, A., Regan, C., Cooper, R. E., Powell, R., Thomas, E., Brennan, G., Rojas-García, A., Lloyd-Evans, B., Johnson, S., & Simpson, A. (2024). The use and impact of surveillance-based technology initiatives in inpatient and acute mental health settings: a systematic review. BMC medicine, 22(1), 564. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03673-9

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Ecological systems theory (1992). In U. Bronfenbrenner (Ed.), Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development (pp. 106–173). Sage Publications Ltd.

Deering, Kris, Chris Wagstaff, Jo Williams, Ivor Bermingham, and Chris Pawson. 2023. ‘Ontological Insecurity of Inattentiveness Conceptualizing How Risk Management Impact on Patient Recovery When Admitted to an Acute Psychiatric Hospital.’ International Journal of Mental Health Nursing Early View: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13245

Solanki, J., Wood, L., & McPherson, S. (2023). Experiences of adults from a Black ethnic background detained as inpatients under the Mental Health Act (1983). Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 46(1), 14.

Verbeke E, Vanheule S, Cauwe J, Truijens F, Froyen B. (2019) Coercion and power in psychiatry: A qualitative study with ex-patients. Soc Sci Med. 2019 Feb;223:89-96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.031. Epub 2019 Jan 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.031

Photo credits

- Adapted from Jacquelinecp16 on Wikimedia Commons

- Photo by Dylan Gillis on Unsplash

- Collage by Simon