It is always a privilege to write for the Mental Elf, and I guess I have been exploring the woodlands long enough for them to set me a blogging challenge: writing a summary of the early evaluation of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Trailblazer Programme (Ellins et al., 2023). This is not your standard research article but instead a long document covering several research questions and methods. Therefore, the aim of this blog is to reflect on some of the findings rather than summarise the review (as the review already has a helpful summary).

So here goes! I do feel a little like the elf who has been challenged to try the new ‘grey literature’ mushroom first to see if it’s safe! Let’s see if it is.

Mental health services in schools: the context

Mental health issues in children and young people (CYP) are on the rise (Pitchforth et al., 2019), and have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. It has therefore been proposed that an obvious way of tackling this is to place mental health services in schools. This has been trialled before with several other projects such as:

- Targeted Mental Health in Schools (TaMHS) from 2008-2011

- Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), launched in 2007 and extended to child and young people’s services in 2011

- Schools Link Pilot, launched in 2015

During this time period, several government documents were published, including Future In Mind (2015) and Five Year Forward View for Mental Health (2016). This culminated in the Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision green paper (2017), which set out three key actions for supporting CYP mental health:

- A trained and dedicated Senior Mental Health Lead in every school

- Mental Health Support Teams (MHSTs) linked to every school

- Reduced wait times for CYP in need.

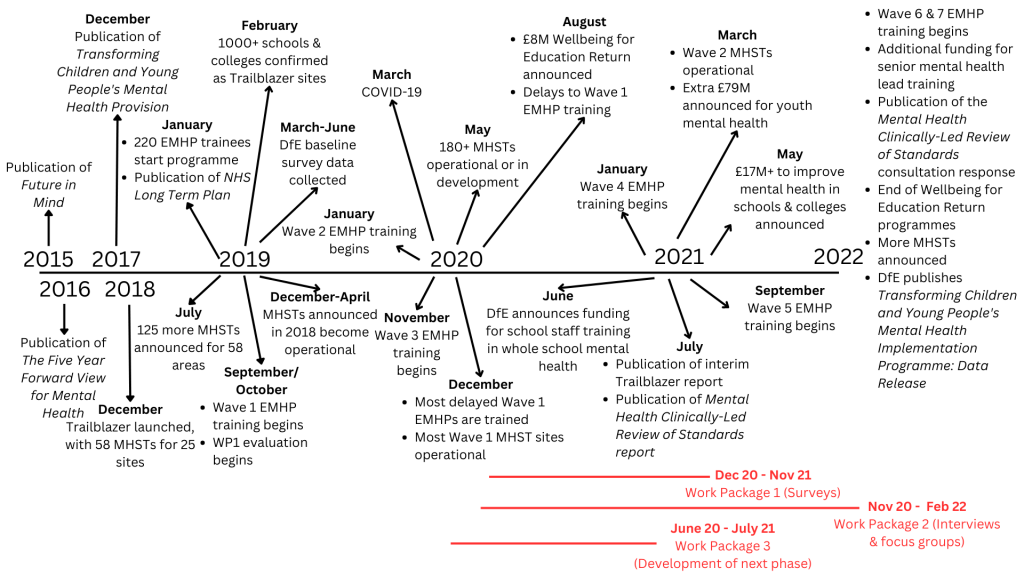

This would be rolled out in phases across the country (see Figure 1 for a timeline), beginning with trailblazer sites.

Figure 1. A timeline of the Trailblazer programme and the relevant broader context. [Click to full full sized figure]

- Providing direct support to CYP with mild to moderate mental health issues

- Supporting education settings to introduce or develop their whole school/college approach to mental health and wellbeing

- Giving advice to staff in education settings and liaising with external specialist services to help CYP get the right support and stay in education.

The current report evaluates the development, implementation and early progress of the first 58 MHSTs embedded in 25 Trailblazer sites and involving 1,050 schools and colleges, with the aim of “scoping and developing an evaluation protocol for a longer term summative assessment of the programme’s outcomes and impacts”. Of note, this work has been hugely impacted by COVID-19, which is reflected in the report, but not the focus of this blog.

The Children and Young People’s Mental Health Trailblazer programme launched in 2018 to provide better mental health support to children and young people in schools in England.

Methods

A broad range of data was collected through a variety of methods and from different stakeholders throughout the project. A youth advisory group with lived experience of mental ill health were involved throughout.

Surveys

Two surveys were sent to schools/colleges, with response rates ranging from 17% (second survey) to 30% (first survey). At least 2 responses were received from every Trailblazer site.

Two additional surveys were conducted with stakeholders who were key to implementing Trailblazer MHSTs (e.g., managers, education leads). Both surveys had a 26% response rate and there was at least one response from every Trailblazer site.

Interviews

Six sites were selected as case studies, with one site later withdrawing. Interviews with 71 stakeholders were carried out across these 5 sites between July 2021 and February 2022.

National and regional leads were also interviewed twice (40 individuals in total, with 26 in each round and 12 taking part in both interviews).

Group interviews took place with the national programme team from the Department of Health and Social Care, Department for Education, NHS England, Improvement and Health Education England, and with key personnel from two universities delivering EMHP training. A final interview involved a senior advisor on CYP mental health to NHS England and Improvement, resulting in 8 interviews with 21 people.

Qualitative data was analysed using a thematic framework method.

Focus groups

Two focus groups with CYP were also conducted, with self-selected participants with a mixture of demographics (e.g., primary and secondary school, male and female, contact or no contact with an MHST). All data was anonymised.

Secondary data

Analyses drew on a wide range of secondary data sources, including data that had been collected for the previous work packages, data from the Department for Education (DfE) baseline surveys, financial data, scoping review data, and more.

Results

This review does not cover the impact of Trailblazers on mental health outcomes. Rather, it looks at how well the programme has been implemented, with reflections on what does and doesn’t work as MHSTs continue to be rolled out across the country. This blog summarises some of the key themes across the report, but does not cover all findings.

Facilitators to implementation

It is clear that there are a number of facilitators to ensure effective implementation of MHSTs (Mental Health Support Teams) in schools.

Collaboration was one of the most recurring themes, with emphasis that MHSTs need to work in partnership with their schools. This was often facilitated by having someone on the MHST who understood educational settings (i.e., had previously worked in education), but was also aided by effective communication and strong relationships between the partners. It was noted that where there were previously strong relationships between schools and mental health services, there was better implementation at the start of the programme. In addition, it helped if schools had buy-in from senior leadership and an engaged mental health lead, and there was clear governance, leadership, and encouragement of a whole school approach.

The MHST staff were most effective when they were professional, reliable, informative, and proactive, but also when they were able to act or respond promptly to referrals/queries. Flexibility was also seen as a facilitator, where MHSTs could tailor their support and ways of working to individual education settings. It is worth noting that this tailoring was based on what school staff thought was needed; only in a very limited number of settings were the views of children and young people or parents and carers taken into account. When these perspectives were considered, it was seen as being effective. Finally, a key facilitator was a commitment to a whole school approach.

Barriers to implementation

Barriers to effective implementation were experienced by both MHSTs and schools.

For schools, some simply did not engage with the MHSTs in a way that allowed the programme to be fully embedded, for reasons such as:

- Competing commitments and priorities of senior mental health leads resulting in a lack of engagement

- Perceptions that MHSTs were limited in capacity to meet the needs of the setting

- Poor communication leading to a misunderstanding/mismatch between school expectations and available provision

- Pupils not being referred due to perceptions of MHST referrals being unsuitable

- Schools wanting to focus on intervention and MHSTs wanting to focus on prevention

- Lack of trust in MHST experience and/or knowledge

- Past (poor) experience of short-term mental health programmes

- Mental health not seen as a priority for the school

- A sense that they (the schools) were being dictated to (see below).

Some further challenges arose due to the way that the project itself ran and the impact of COVID-19, including:

- Frequent MHST staffing changes and high staff turnover affecting relationship-building

- Delays in the senior mental health lead training, making it hard for schools to work effectively with MHSTs

- Lack of physical space in schools for MHSTs

- EMHPs trained to deliver very specific interventions that are not appropriate for all groups and therefore excluded some CYP from accessing support

- Parents offered support but not consistently engaging

- Long waiting times to access MHSTs

- Support needing to be delivered remotely

- Considerable admin associated with the service and required to make referrals.

Benefits of MHSTs

However, educational settings did identify some benefits of MHSTs, including:

- Support for school staff and parents/carers

- Increased capacity to support CYP mental health needs

- Earlier identification and quicker access/intervention

- Raised awareness

- Improved service links.

From the perspectives of CYP, the authors note a perceptible shift in attitudes and language around mental health and wellbeing. It is clear that where the MHSTs were fully embedded in the school, pupils were better able to talk about mental health (increased mental health literacy), better able to seek help (increased access), and better able to deal with difficult emotions or situations (increased self-management). Where the pupils were aware of MHSTs, their views were generally favourable, reinforcing the importance of working at a whole school level.

Facilitators for implementing Mental Health Support Teams within schools were identified, including effective communication, support from those in leadership roles, and collaboration.

Conclusions

Overall, the Trailblazer programme has been largely positive, especially given the challenging circumstances of COVID-19. However, there is substantial learning that can be taken from this review as to what facilitates the most effective working partnerships between schools and mental health services. It also identifies key gaps that the MHSTs might need to fill that go beyond their original scope, which perhaps requires a rethink of the programme.

Barriers to implementing Mental Health Support Teams within schools was also found, including lack of engagement, poor communication, conflicting priorities, and limited capacity. COVID-19 also had a big impact on the programme.

Food for thought

I am really privileged that, as part of my work as coach for the School Mental Health Award, I have spoken to over 200 schools in the past 4 years about their mental health and wellbeing provision, many of whom have been involved with the Trailblazer programme. It is clear that they have found the experience overwhelmingly positive, and I have witnessed first-hand a wide variation in how schools have worked with their MHSTs and EMHPs. As such, there are a couple things that I wanted to reflect on.

Firstly, it seems that the project was rushed in its set up, meaning schools took a backseat in the development of the MHSTs. Given that the end users are pupils and that the conduits are schools, it is vital that schools are fully involved in the development and implementation process of such programmes. It appears that many MHSTs took a more clinical approach to development (presumably because most people employed had this background) and have not necessarily taken into account how schools operate, or the potential lack of mental health literacy of school staff. This was, as suggested by the report, further exacerbated by senior mental health lead training being delayed, meaning schools may have not had the knowledge needed to contribute. Ultimately this appears to have led to two ‘types’ of MHSTs – clinical versus holistic. The holistic set up was usually where there were already strong relationships between the health and education sectors, allowing for more flexibility and schools being more readily included in driving the provided support.

A further issue could be the funding. Whilst the MHSTs and regional leads felt that they had sufficient funding, schools did not. There is currently a recruitment and retention crisis in education, and staff are already stretched to breaking point in covering vacancies and sickness. The senior lead roles were clearly crucial to the programme’s success, but if this is an additional responsibility taken on by a member of the senior leadership team, it is unlikely to be a priority or a role given enough time. As seen above, the effectiveness of the programme depended greatly on the relationships and collaboration between schools and MHSTs; it was noted that where the mental health role in school was split between two people into strategic and operational, the workload was better spread, leading to more effective implementation.

Although the Trailblazer programme was positive, schools seemed largely uninvolved in the development of the programme, leading to a lack of holism between schools and support teams which may have hindered effectiveness.

Next steps

Finally, before I make my way back out of the woodland, I would like to reflect on ‘what next?’

Both this evaluation and findings from an earlier work package highlight some key learning as this project rolls out. Given that the Trailblazers have demonstrated good progress in meeting their key objectives and our knowledge of links between mental wellbeing and academic achievement, you would think all schools would jump at the chance to engage with MHSTs.

But they do not.

Teachers are often not trained in mental health, and many do not engage with it due to a focus on other demands within education. Many of those most interested have already engaged – so how do you engage schools that simply do not see this as a priority, particularly in light of the importance of collaboration and communication? Going forward, national and regional leads will need to consider not just the barriers faced by participating schools, but also how to engage with reluctant schools.

Looking to the future, consideration needs to be given to how to encourage schools to engage with the programme when mental health is not a priority.

Statement of interests

No conflicts of interest.

Links

Primary paper

Ellins, J., Hocking, L., Al-Haboubi, M., Newbould, J., Fenton, S-J., Daniel, K., et al. (2023). Early evaluation of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Trailblazer programme: A rapid mixed-methods study. Southampton: NIHR Health and Social Care Delivery Research Topic Report.

Secondary paper

Ellins, J., Singh, K., Al-Haboubi, M., Newbould, J., Hocking, L., Bousfield, J., et al. (2021). Early evaluation of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Trailblazer programme: Interim report. National Institute for Health Research,

Other references

Department of Health, & Department for Education (2017). Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: a Green Paper.

NHS England (2015). Future in mind: Promoting, protecting and improving our children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Department of Health.

McCarthy, M. (2023). Are the kids alright? Emergency help for suicide and self-harm during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Mental Elf.

Pitchforth, J., Fahy, K., Ford, T., Wolpert, M., Viner, R. M., & Hargreaves, D. S. (2019). Mental health and well-being trends among children and young people in the UK, 1995–2014: analysis of repeated cross-sectional national health surveys. Psychological Medicine, 49(8), 1275-1285.

Powell, L. (2018). Mental health stigma in schools: helping young people access support. The Mental Elf.

The Mental Health Taskforce (2016). The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health. NHS England.

Photo credits

- Photo by Jonathan Borba on Unsplash

- Photo by Adam Winger on Unsplash

- Photo by La-Rel Easter on Unsplash

- Photo by Max Goncharov on Unsplash

- Photo by Debby Hudson on Unsplash