The day you get married, the days your children are born, the evening your team wins the Champions League for the fifth time. These are all occasions etched in our memories as full of joy and time for celebration, at least that’s what most of us think.

I really did enjoy that night in Istanbul, but in actual fact my wedding day was a pretty stressful and anxiety-inducing occasion (“Why won’t everyone stop looking at us and smiling?”). The arrival of all of our children was of course incredible and miraculous (“We made this!?”), but by the time my youngest child was born I was not in a good headspace and my mental health went from bad to worse over the following months. I experienced a severe episode of depression that lasted well over a year and it took a long time for me to seek help.

During the first few weeks after the birth, my wife and I (with our new baby) met a number of experienced health professionals. Some of them stood out as amazingly caring expert clinicians, whereas others were memorable for less positive reasons. Of course, many people asked my wife how she was doing, and on a few occasions she was asked directly about her mental health (by health visitors and midwives). Of course, this is good practice; we know that at least 10% of women are affected by postnatal depression, so it makes sense to pick it up early and help Mums and children to cope.

Mums and Dads with postnatal depression often present with very different symptoms; some traditional depressive symptoms, but others such as aggression, irritability and frustration.

“I’m fine. Tired, but you know…”

Lots of people (especially my friends) asked me how I was doing during the first few weeks of my second round of fatherhood, but of course I simply answered: “I’m fine. Tired, but you know…” No health professionals asked me if I was OK, in fact I was generally ignored during our enormous number of perinatal appointments. I was never asked directly about my mental health; by professionals, family or friends. It took a long time for me to realise that I was clinically depressed and still now (3 years later) I’m barely beginning to process the emotional turmoil that we all went through. I felt more angry, restless and useless than sad, but of course depression feels very different for different people. Interestingly, these “acting-out” or externalising symptoms are much more common in men.

When I did finally summon up the courage to see a GP about my depression, he made no eye contact, printed off a PHQ-9 checklist and pushed it across the desk towards me without saying a word. I left with the knowledge that he couldn’t help me find a talking therapist (he curtly told me so), but with the antidepressants I went there to get, and his parting words: “they probably won’t work”!

We know that about 5-10% of men experience clinical depression during the perinatal period (Paulson et al, 2010), and 5-15% are affected by anxiety disorders (Leach et al, 2016), but we have very few ways to screen for postnatal depression in fathers. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al, 1987) is used to screen new mothers, but it doesn’t have questions about somatisation (psychological distress presenting as physical symptoms) or externalising behaviours (e.g. physical aggression), so it’s less useful in men.

A recent study carried out by researchers in Sweden aimed to develop a better tool for screening depression in fathers of children aged 0-18 months. Their two main aims were to:

- “investigate whether depressive symptoms in fathers postnatally comprise both typical depressive symptoms and externalizing, depressive equivalents”

- “test the hypothesis that the addition to the EPDS of items addressing depressive equivalents would result in increased sensitivity in detecting fathers with elevated, burdening depressive symptoms, using as reference Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II), a DSM-5 compatible measure of depression.

It seems to me that this is a sensible piece of research to be summarising on #DadsMHday.

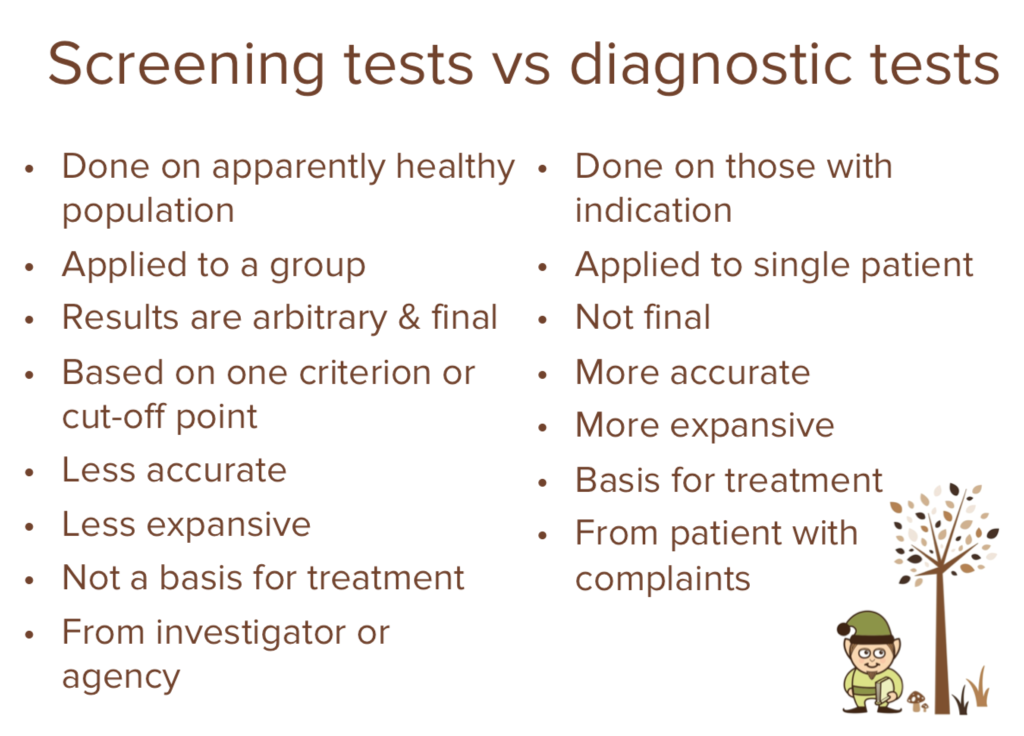

Screening dads for depression is different from diagnosing dads with depression.

Methods

The study involved over 400 men completing a variety of online screening tools to measure their depressive symptoms and depressive equivalents:

- BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory II (Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996) A 21-item and broadly used self-report instrument for depression

- EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (Cox et al, 1987) A 10-item self-report questionnaire for screening depression in women after childbirth

- GMDS: Gotland Male Depression Scale (Walinder & Rutz, 2001) A 13-item self-report measure of male depression symptoms.

The men in the study had a mean age of 34 years, most (62.8%) had one child, 26.9% had two children and 10.3% had three or more kids. The majority (76%) had post-high-school education and most (88%) were employed and earned more than average, so the sample was biased towards well-paid Dads with higher education levels than average.

During the study, about a third of the men were on parental leave and another third had previously been on parental leave. The partners of 21% of participating men had or were receiving professional help for depressive symptoms.

Dichotomous variables based on scale cut-offs were created from each depression scale. Cross-tabulations of these variables were performed in order to test whether the scales converged in detecting suspicion for depression.

Sensitivity and specificity analyses (using ROC curves) were carried out comparing the EPDS to a new screening instrument that the researchers developed as part of the study (the Edinburgh-Gotland Depression Scale (EGDS)). They used the BDI-II instrument as a reference; to indicate at least mild depression.

If you want to find out more about sensitivity and specificity and how they relate to screening tests, I highly recommend this Wikipedia page.

Edinburgh-Gotland Depression Scale (EGDS)

This new scale combines 12 questions from the EPDS and GMDS scales in an attempt to find a screening tool that works better for new dads at risk from postnatal depression.

- I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things.

- I have felt scared or panicky for no very good reason.

- I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping.

- I have felt sad or miserable.

- I/others have noticed that I have a lower stress threshold – I am more stressed out than usual.

- I feel that my behavior has altered in such a way that neither I myself nor others can recognize me, and that I am difficult to deal with.

- I have looked forward with enjoyment to things.

- I/others have noticed that I am more aggressive, outward reacting, difficulties keeping self-control.

- The thought of harming myself has occurred to me.

- I/others have noticed that I am more irritable, restless and frustrated.

- Things have been getting on top of me.

- I have noticed that I have a greater tendency for self–pity, to be complaining or to seem “pathetic”.

The EGDS combines questions about low mood and stress, with others about externalising behaviours such as aggression and irritability.

Results

Depressive symptoms

- 28% of fathers reported symptoms above the BDI-II cut off (≥ 14) for mild depression

- 14% of fathers reported symptoms above the BDI-II cut off for (≥ 20) moderate depression.

Depressive symptoms vs no symptoms

The researchers compared men with mild, moderate and severe depressive symptoms, to men below the BDI-II cut off (≥ 14) for mild depression and found the following:

- There were no differences in age, educational levels, or age of youngest child

- 32.2% of fathers with children 13-18 months old reported symptoms above the cut off, compared to 25.9% and 26.8% of fathers with infants aged 0-6 months and 7-12 months respectively

- 28.8% of fathers who had been on paternal leave returned above cut off scores, compared with 24.8% in fathers who had not been on parental leave

- Fathers with more than one child more frequently scored above the cut off

- Fathers were more likely to report higher scores if the mothers of their children were also receiving help for depression. The more severe the depression in the father, the more likely it was that the mother was also receiving help

- 82.8% of fathers who reported above cut off scores had not sought or received professional help for their depression

- 2 of the 122 fathers who scored above the cut off, reported will or intent to take their own lives, and 42 fathers reported thoughts of harming themselves.

Convergence of depression screening scales

The authors cross-tabulated the depression scores above and below the cut off points, which revealed convergance between the different scales:

- 81.5% between BDI-II and EPDS

- 84.2% between BDI-II and GMDS distress subscale

- 78% between GMDS and EPDS

The Edinburgh-Gotland Depression Scale (EGDS)

The authors combined the 17 questions from the EPDS and GMDS scales and then did some clever ‘item reduction’ work to remove 5 questions and leave a 12-question instrument, which they then tested for sensitivity and specificity. They used a number of cut-off values and tested the new EGDS scale alongside the EPDS.

| Internal consistency, sensitivity and specificity of the EPDS and EGDS, evaluated against BDI-II (cut-off ≥ 14) | ||||||||

| EPDS | EGDS (12 items) | |||||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.85 | 0.90 | ||||||

| AUC | 0.929 | 0.937 | ||||||

| Cut-off value | ≥ 9 | ≥ 10 | ≥ 11 | ≥ 12 | ≥ 9 | ≥ 10 | ≥ 11 | ≥ 12 |

| Sensitivity | 81.9% | 75.9% | 65.5% | 55.5% | 80.5% | 82.8% | 75.0% | 69.0% |

| Specificity | 81.5% | 89.4% | 93.4% | 96.0% | 90.5% | 87.1% | 91.4% | 95.0% |

So what does this all mean?

These sensitivity and specificity scores are not good enough for a screening test. The sensitivity scores are too low, which means that many dads with postnatal depression would not be picked up by the test (false negatives), and the specificity numbers are too low, which means that many dads without postnatal depression would wrongly be identified as having the condition (false positives).

The new 12-question EGDS (Edinburgh-Gotland Depression Scale) screening test did not accurately screen new fathers for postnatal depression.

Conclusions

Existing screening tests for postnatal depression in new dads aren’t good enough. This study and other related papers in the field are trying to create something better by combining the EPDS to screen traditional depressive symptoms with elements of the GMDS for depression equivalent symptoms. This is a laudable aim, but will it work?

A fair answer from this research is probably: not yet. The 12-question Edinburgh-Gotland Depression Scale (EGDS) is a step forward in that it combines questions that are perhaps a better fit for the range of symptoms experienced by many new dads with depression. However, this current iteration of the test is not ready for rolling out nationwide, and this is something that the authors accept in their measured conclusion:

This is an important first step towards identifying a set of items suitable for the reliable assessment of depressive symptoms in fathers in the postnatal period.

Can others build on this work to produce a screening test that accurately screens for postnatal depression in new dads?

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

- The authors should be commended for focusing on an area of clinical need where a step forward could have a big impact on lives

- The study methodology was good and the findings are relatively robust.

Limitations

- The study had a small sample size, and given the online nature of the research a bigger sample would be hoped for in future work

- The depressive symptoms were self-reported by the men taking part, which makes them susceptible to recall bias

- The study population was biased towards men with higher than average education and income

- The screening instruments were assessed against the BDI-II test, and not a clinical interview, which would have been more reliable.

Implications for practice

So, should we screen new Dads for depression? I think the answer at present is no, simply because no gold standard screening test exists for depression in new dads. The sensitivity and specificity of existing screening tests is low and the evidence we have is based on relatively small sample sizes. If we did implement a screening test like the EGDS tool developed in this study, we would have to be prepared for the consequences of lots of false positives (men wrongly identified as having depression) and false negatives (men wrongly identified as not having depression).

Postnatal depression is a common public health problem with significant morbidity and mortality. Early treatment is certainly of benefit and likely to result in better outcomes. So the obvious questions for research in this area are:

- Can we develop a screening tool that has better sensitivity and specificity than existing tools?

- Can screening be delivered in a cost-effective way via digital technology? A follow on question would be: Are these measures valid when delivered online?

- If new dads are screened more reliably for postnatal depression, how can they be followed up for diagnostic testing and treatment? i.e. Can services cope with this increased demand?

Is online testing for depression in dads a goer?

Conflicts of interest

I have lived experience of postnatal depression, which probably makes me more likely to want other people to not have to go through the nightmare that we went through. My gut response is to call for all new parents to be screened for postnatal depression, but this blog suggests that the evidence just doesn’t support this yet.

Links

Primary paper

Psouni E, Agebjörn J, Linder H. (2017) Symptoms of depression in Swedish fathers in the postnatal period and development of a screening tool. Scand J Psychol. 2017 Dec;58(6):485-496. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12396. Epub 2017 Oct 20. [PubMed Abstract]

Other references

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. (1996) Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Cox J, Holden J, Sagovsky R. (1987) Detection of Postnatal Depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 782-786. doi:10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [Abstract]

Leach LS, Poyser C, Cooklin AR, Giallo R. (2016) Prevalence and course of anxiety disorders (and symptom levels) in men across the perinatal period: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:675–86. [PubMed abstract]

Maxim LD, Niebo R, Utell MJ. (2014) Screening tests: a review with examples. Inhalation Toxicology. 2014;26(13):811-828. doi:10.3109/08958378.2014.955932.

Paulson JF, Bazemore SD. (2010) Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;303(19):1961–9.

Svenlin N. (2015) Validation of the Edinburgh Gotland Depression Scale for Swedish fathers (PDF). UMEA Universitet, Masters Thesis.

Walinder J, Rutz W. (2001) Male depression and suicide. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16, S21–S24.

Photo credits

- Photo by Nick Stephenson on Unsplash

- Photo by Christin Hume on Unsplash

- Photo by Frederik Trovatten on Unsplash

- Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

- Photo by Courtney Clayton on Unsplash