It is well-established that women in low-income households have an increased risk of developing mental health problems, in particular depression. Studies have found that these women are around twice as likely to develop the disorder compared with those from higher-income households (Hobfoll et al, 1995). Low-income women are also less likely to seek and receive appropriate treatment, in part because of the associated costs (Lennon et al, 2001).

For women who are mothers, this is especially consequential: parental depression has been linked with developmental, emotional and mental health problems in children (McDaniel et al., 2013). In the United States this has been highlighted as a public health concern, and it is increasingly being recognised that community-based services offer valuable opportunities to reach those for whom help is less accessible.

Head Start is a US government-funded service aimed at families at or below the federal poverty level with young children under five. They use a case-management structure to establish a healthy family environment in order to look after the child’s development and wellbeing. Depression affects almost half of the mothers at Head Start. A recent study by Silverstein et al. (2017) examines the efficacy of embedding a depression prevention strategy in the Head Start program.

Depression in low-income mothers is a public health concern.

Methods

Silverstein and colleagues conducted a randomised controlled trial within six Head Start centres in Boston, Massachusetts. From these services they recruited at-risk mothers, defined as those either currently experiencing low mood or anhedonia, or with a recent history of depression (according to a diagnostic interview). As this study was focusing on prevention, those identified as currently experiencing a major depressive episode (MDE) were excluded, along with those with high levels of suicidal ideation.

230 participants were randomised to receive either a problem-solving education (PSE) intervention or the usual Head Start services, and followed up for 12 months.

The primary outcomes were problem-solving skills at 6 and 12 months, and depressive symptoms as measured by the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms bi-monthly (QIDS). However, rather than focusing on continuous scores, the authors operationalised depressive symptoms as the number of times throughout the study that the individual’s QIDS score equalled or surpassed the moderately severe threshold of 11, called ‘symptom elevations’. This was standardised according to the number of assessments completed.

Usual Head Start services include parenting groups, needs assessments, and assistance with accessing food, employment and housing services. The PSE group received six one-to-one manualised problem-solving sessions, which incorporated goal-setting, decision-making exercises, symptom monitoring, and motivational interviewing. Those scoring in the moderate range on two depressive symptoms assessments or in the severe range on one were referred to formal mental health services.

The intervention focused on building problem-solving skills in one-on-one sessions.

Results

- The mean number of symptom elevations was significantly lower in the PSE group: 0.84 (Standard Deviation (SD) 1.39) compared with 1.12 (SD 1.47)

- Depressive symptom scores over time were lower in the PSE group, though not substantially (adjusted difference, 0.90; 95% Confidence Interval (CI), 0.09 to 1.71)

- There was no significant difference between groups in terms of the number of participants meeting criteria for a major depressive episode during follow-up

- Curiously, though, linear regression models showed no significant difference between groups in terms of problem solving scores at either 6 or 12 months.

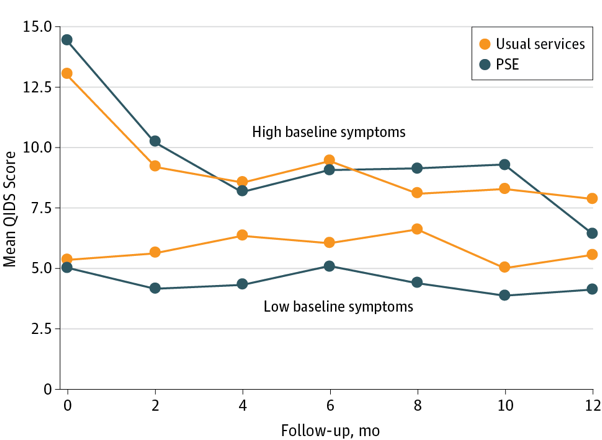

Although mean depressive symptoms did not differ between the two groups at baseline, more participants in the PSE group had scores above the moderately severe threshold. The authors therefore conducted additional stratified analyses with two groups: high (11 and above) and low (below 11) baseline symptoms:

- The low group showed a significant benefit of PSE in terms of symptoms over time (adjusted difference, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.36 to 2.29). The high group, though, showed no significant difference in scores between treatment groups (adjusted difference, -0.33; 95% CI, -2.10 to 1.44). Group by time interaction terms were nonsignificant

- In the low group, the authors note that PSE ‘exerted a preventive effect on symptom elevations’. Cox proportional hazards regression models estimated an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.52 (95% CI, 0.28 to 0.95) in favour of PSE. This effect was not present in the high group.

Figure 1: Depressive symptoms in the Head Start group compared with the PSE group, separated by baseline symptom severity.

Strengths and limitations

Aside from investigating a socially important and worthwhile topic, this study has a number of strengths:

- Current Head Start employees screened participants and the intervention was implemented by lay workers with only 3 days total of training. Treatment fidelity was shown to be high, and participants attended a mean of 4.64 (SD 2.06) sessions. This demonstrates the practicability of the intervention

- The study showed really good retention rates of participants over a long follow-up period (93.8% in the PSE group and 89.1% in the Head Start group), and imputing missing data did not change the analysis results. This provides support for the validity of the results

- This study has good external validity owing to that fact that the intervention is compared with existing community services, the realistic alternative for these mothers if community-based mental health care initiatives are not available.

However, the analysis of the study results mean the findings are overstated:

- The moderate symptom boundary of the QIDS is a fairly arbitrary cut-off point in the context of MDE prevention; the authors themselves identify its lack of robustness. MDE incidence (using a diagnostic measure) or change in QIDS symptom score would have been more meaningful primary outcomes

- As those with severe symptoms were excluded from the study during screening, it seems unnecessary to stratify the analysis based on baseline symptom severity, particularly as there was no imbalance between groups in terms of mean depression symptom scores at baseline. We should be careful not to place too much weight on the results of the stratified analysis.

The study showed really good retention rates of participants over a long follow-up period.

Conclusions and implications

These results provide some evidence that this problem-solving education (PSE) intervention could reduce depressive symptoms and prevent their worsening. Whilst evidence in the sample as a whole is not very strong, the case becomes more convincing when looking only at those with low depressive symptoms at baseline. This is in line with the intervention being aimed at prevention; it may be that a more intensive treatment approach (for example, longer sessions) is needed for those already showing moderate symptoms.

Whilst we must be careful not to overstate the magnitude of the effect, this study demonstrates that utilising a community-based organisation to deliver mental health interventions can be both feasible and efficacious. Community-based treatment could substantially increase the access and engagement of those living in poverty, particularly if interventions are linked with trusted services such as Head Start that do not carry the stigma specialist services do. However, in this study 22% of those originally identified as at-risk declined to be screened; finding out why may be helpful.

It is difficult to hypothesise whether similar problem-solving interventions are likely to be efficacious, because the mechanism of action of this intervention is unknown. The lack of change in problem-solving abilities seems to suggest it may be that common factors such as regular one-to-one contact with a supportive individual are responsible for the treatment effect observed, but further investigation is warranted.

Reducing and preventing depressive symptoms in mothers, particularly those already disadvantaged, is extremely valuable, with implications for the quality of life of many women as well as their children. This study is a promising step towards doing so in a more accessible way.

This study demonstrates that utilising a community-based organisation to deliver mental health interventions can be both feasible and efficacious.

Links

Primary paper

Silverstein M, Diaz-Linhart Y, Cabral H, et al (2017) Efficacy of a Maternal Depression Prevention Strategy in Head Start: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017. [PubMed abstract]

Other references

Ammerman RT. (2017) Opportunities and Challenges in Addressing Maternal Depression in Community Settings. JAMA Psychiatry 2017. [PubMed abstract]

Hobfoll SE, Ritter C, Lavin J, et al (1995) Depression Prevalence and Incidence Among Inner-city Pregnant and Postpartum Women. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995 63(3) 445-453. [PubMed abstract]

Lennon MC, Blome J, English K. Depression and low-income women: Challenges for TANF and Welfare-to-Work policies and programs (PDF). Research Forum on Children, Families and New Federalism; National Center for Children in Poverty. Mailman School of Public Health: Columbia University 2001.

McDaniel M, Lowenstein C. Depression in Low-Income Mothers of Young Children: Are They Getting the Treatment They Need? (PDF). Washington, DC: The Urban Institute 2013.

Photo credits

- Photo by Johann Walter Bantz on Unsplash

- Greg Parish CC BY 2.0

[…] Overview via the Mental Elf […]

[…] Overview via the Mental Elf […]

I would firstly like to thank the author of the blog post for writing such a concise and accessible review of a paper that addresses a technically difficult topic. I do agree with the conclusions of the blog post about the perils of overstating the importance of these findings. My main concern with the paper is the fact that the authors proceeded to run subgroup analyses following a null effect in the full sample without mentioning such plans in their otherwise detailed trial protocol (https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01298804). The results could be due to a statistical artefact as the authors neglected to provide any theoretical justification for such analyses in the introduction. It would be interesting to see whether the effects are replicated in future studies that explicitly mention such tests in their trial registration protocols.

[…] Source link […]