Intimate partner violence (IPV) involves the deliberate perpetration (or intended perpetration) of physical, sexual, psychological, financial or other forms of harm towards a partner or ex-partner. IPV predominantly affects women victims, but also impacts children, and causes a range of other forms of harm (Garcia-Moreno et al, 2006).

One in three women report having experienced IPV, which is related to greater occurrence of mental and physical health problems, and is also associated with other forms of adversity and disadvantage, including poverty, unstable housing, and social exclusion.

IPV is commonly encountered by health professionals, who may be uniquely well-placed to identify, assess and reduce risk of IPV in affected families. Effective interventions to reduce IPV in women using healthcare are much needed. Many studies have proposed and examined the possibility that training, guidance, and pathways specific to IPV, could improve how well services identify and respond to IPV. However, there is limited good quality evidence on whether these types of intervention work to reduce the occurrence of violence, or effects on wellbeing. Identifying and safely managing IPV is particularly important and potentially harmful in the perinatal period (Howard et al, 2013), and women during this time of life are usually in contact with health services, making this stage of life relevant for developing potential health service-based strategies for reducing IPV.

One in three women report having experienced intimate partner violence, which is related to greater occurrence of mental and physical health problems, and is also associated with other forms of adversity and disadvantage, including poverty, unstable housing, and social exclusion.

This paper examined the impact of an established home-based health intervention, called home visitation, on the occurrence of IPV. Home visitation is described in the paper as a program of prenatal and infancy home visiting provided by nurses to disadvantaged first time mothers.

An earlier randomised trial of home visitation had shown that it reduced abuse and neglect of children over a period of 15 years of follow up (Olds et al, 1997). This previous study did not show any differences in IPV, despite the intervention incorporating integrated screening and educational information for clinicians. Professionals providing that particular intervention did not report feeling adequately informed regarding the identification and management of IPV, and did not feel that the programme was sufficient to meet the needs of women disclosing IPV. Therefore the authors decided to add another IPV-focused intervention to the existing programme, and test this in a trial. It is this trial presented in the paper.

Home visitation is described in the paper as a program of prenatal and infancy home visiting provided by nurses to disadvantaged first time mothers.

Methods

Randomised trials take a large number of “units”, usually individuals, and randomly allocate each individual to either an intervention or a control group. If this process is truly random and occurs in a large enough group of individuals, then researchers can work out whether the intervention is effective or not. Some interventions are best delivered not to individuals but to whole groups of individuals, such as health services, and so evaluating these involves randomising not individuals, but whole teams, or groups of people. In trial design, these large aggregated units are referred to as clusters, and give rise to the term cluster randomised controlled trial.

Sites for this trial were nurse home visitation programmes. This trial was carried out between May 2011 and May 2015. The investigators applied for ethical approval, established a monitoring committee to review any adverse events, and consented all participants. For a site to be eligible for inclusion in the study, they had to have had no involvement in the development or piloting of the trial of the previous intervention. Within each site, only women who were 16 and over, spoke English, and met previous programme criteria were eligible. Each site was grouped according to number of nurses (1-7, more than 8), so that equal numbers of these sites were in the intervention and the control arms of the trial.

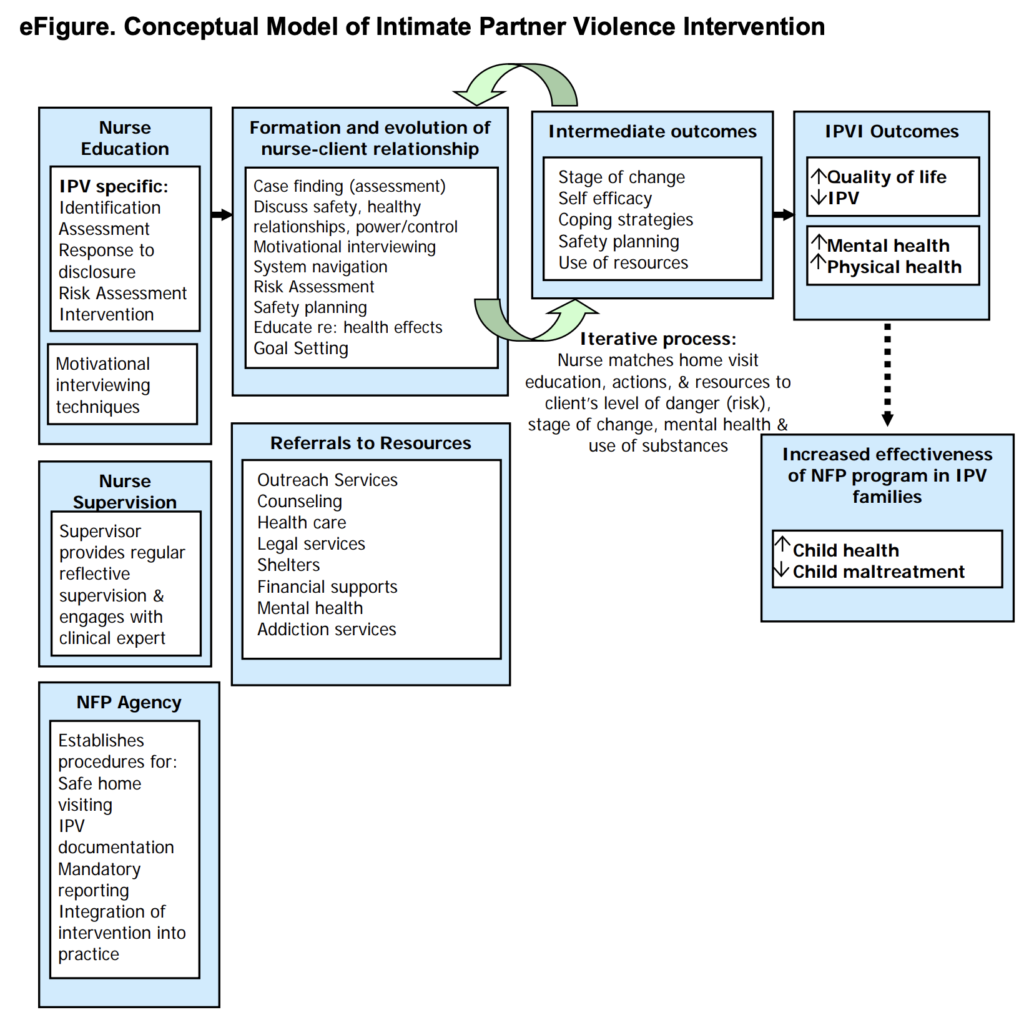

Where sites were allocated to the intervention, nurses delivered a standard home visitation programme supplemented with a dedicated IPV intervention. This intervention included a number of components, summarised in the figure below (taken from the original paper’s Supplementary material). These included educating nurses, guidelines on supervision, and clinical pathway information. The intervention also included components tailored to the particular individual, which incorporated assessment of safety, empathic response to IPV disclosure, risk assessment, empowerment intervention, mental health and substance use assessment, and service navigation (where the nurse would point the participant to relevant external organisations, e.g. a domestic violence organisation, or places to get legal, housing, or health and social care services). In particular, nurses in the intervention group delivered a model of nurse home visitation that emphasised discussions of safe relationships, multiple strategies of IPV assessment, immediate risk assessments for participants experiencing abuse, and tailored interventions for abused women (including support for disengaging from the abusive partner).

The control intervention was a “standard” nurse home visitation programme, involving a maximum of 64 home visits from early in pregnancy until the child’s second birthday. Each visit addressed personal health, environmental health, life course development, maternal role, family and friends, and health and human services. Nurses at sites allocated to the control group did not receive specific training on IPV. Control group patients were assessed with a screening tool for IPV at three points in time during the study. Women in the control group received usual care in the event that they disclosed IPV.

To measure outcomes, participants were interviewed by research assistants both in person and by telephone, every 6 months. Participants were compensated with $25 vouchers for completing the baseline interview and $50 for each subsequent interview. The primary outcome for the study was quality of life, measured using a questionnaire. Secondary outcomes were recurrence of IPV, measured using a scale for four domains, which were: severe combined abuse, emotional abuse, physical abuse, and harassment. They also assessed participants for PTSD, depression, alcohol and drug use, and self-rated global health and wellbeing.

This paper evaluated an intervention of a nurse-delivered home visit programme incorporating specific intervention components for intimate partner violence (IPV), summarised in the above figure. NFP: Nurse-Family Partnership.

Results

15 sites were randomised, incorporating a total of 178 nurses specifically employed to deliver the intervention across both groups. An average of 33 patients were enrolled per site, with a total of 492 participants participating overall and followed up for at least 24 months. Participants were around 20 years of age, and two thirds were white. Around half had graduated from high school, and 80% were single.

Quality of life improved in both groups. However, there were no statistical differences in quality of life, or in any of the secondary outcomes.

Quality of life improved in both groups, but there were no statistical differences in quality of life, or in any of the secondary outcomes.

Implications

This trial found that a specific IPV intervention added to a standard home visit programme delivered by nurses did not improve quality of life, or reduce the occurrence of IPV. This could have been because the standard programme central to both arms of the trial was so effective that this limited the ability of the trial to identify large differences between the groups. The standard programme focused on housing, mental health, poverty, and social support, and these “generic” components could be more beneficial or as beneficial to mothers, as a “specific” added focus on IPV.

The authors suggest that the relatively small number of clusters that were randomised introduced possible bias because of demographic differences between clusters, e.g. in the proportion of Hispanic/Latina women enrolled. They suggest that statistical adjustments had limited impact on differences they found, although the interpretation of this adjustment is also limited by the number of clusters. It is also not clear to what extent the intervention was actually delivered; only a quarter of women disclosing IPV received a risk assessment and less than half received one or more tailored intervention component.

This trial was a large undertaking. Although disappointing on the face of it, and counterintuitive, the results of this trial do suggest that properly diagnosing and referring IPV can make a difference, even without specific training/interventions focused on IPV. Participants in the trial were monitored every six months and interviewed in depth, and this could in itself have made a difference. This is important, because developing services that are oriented to the identification and assessment of IPV, incorporating appropriate staff training and support could improve safety, without having to intervene on particular individuals.

This study has limitations, and we should not jump to the conclusion that all dedicated professional training and guidance interventions for IPV are ineffective, but the results may suggest alternative strategies are needed.

These results suggest that properly diagnosing and referring intimate partner violence (IPV) can make a difference, even without specific training/interventions focused on IPV.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

Jack, S. M., Boyle, M., McKee, C., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, C. N., Scribano, P., MacMillan, H. L. (2019). Effect of Addition of an Intimate Partner Violence Intervention to a Nurse Home Visitation Program on Maternal Quality of Life: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 321(16), 1576-1585. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3211

Other references

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH, Health WHOM-cSoWs, Domestic Violence against Women Study T. (2006) Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet Oct 7 2006;368(9543):1260-1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8

Howard LM, Oram S, Galley H, Trevillion K, Feder G. (2013) Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS medicine 2013;10(5):e1001452. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001452

Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, et al. (1997) Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect: Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA 1997;278(8):637-643.