Social connectedness can be understood as ‘a subjective psychological bond that people feel in relation to individuals and groups of others’ (Haslam C. et al, 2015). This definition restricts the broad concept to a subjective and individual-level social relationship which is relevant to loneliness, a negative emotional state that occurs when there is a discrepancy between the desired and actual social relationships. Loneliness is highly prevalent among mental health service users and associated with a variety of poor outcomes, particularly in cases of depression.

The impact of subjective indicators of social relationships on mental health outcomes is eloquently discussed in Michelle Lim’s recent Mental Elf blog (Do you have my back? Perceived social support, loneliness, and its impact on mental health outcomes). Interventions to address loneliness among people with mental health problems remain in their infancy and new, theoretically-based interventions have been called for (Timothy Matthews’ Mental Elf blog: Tackling loneliness in people with mental health problems).

Due to the strong conceptual and empirical links between social connectedness and loneliness, social connectedness could be considered as a potential antidote to loneliness and a possible target for interventions aiming to reduce loneliness. However, the conceptualisation and measurement of social connectedness was still unclear within the context of mental health. A new systematic review by Hare-Duke and colleagues (Hare-Duke L. et al, 2018) sought to identify the measures of social connectedness among adults with mental health problems and to develop a conceptual framework for social connectedness through the included measures.

Social connectedness can be understood as ‘a subjective psychological bond that people feel in relation to individuals and groups of others’.

Methods

The authors used a systematic review methodology. This entailed a systematic search of electronic databases for papers using a quantitative measure of social connectedness. At least 50% of the study sample needed to be 18-65 years of age and to have a mental disorder. They included papers published in English.

Six databases were searched and the reference lists of included studies were screened. One of the key elements of the methods was to assess the measurement properties using the Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Measures (COSMIN) checklist (Terwee CB. et al, 2012). Nine measurement properties were assessed, including internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, content validity, structural validity, hypotheses testing, cross-cultural validity, criterion validity and responsiveness.

Following the searches, the team then carried out a best evidence synthesis of the resulting measures to provide overall rating for their psychometric properties (positive, indeterminate, negative) with a level of evidence (strong, moderate, limited, conflicting, unknown) (Terwee CB. et al, 2007). In order to develop the conceptual framework, the authors used a modified narrative synthesis approach (Popay J. et al, 2006).

- First, a thematic synthesis of the pooled items from all included measures were used to identify dimensions of a preliminary conceptual framework for social connectedness.

- Second, vote counting was used to calculate frequency of each of these dimensions across the included measures and then factor analysis results from the scale developers were compared against the conceptual framework.

- Third, the robustness of the synthesis was evaluated through a sensitivity analysis of measures rated as having good content validity.

Results

A total of 28 studies and 21 measures of social connectedness were included. The samples covered a wide range of mental disorders and were recruited from different settings.

Measures of social connectedness

Of the 21 measures, 16 had only positively phrased items (social connectedness), whilst 5 had a mix of both positive and negative items (social disconnectedness). Most of the measures had limited evidence for their measurement properties with none having data for all 9 COSMIN properties and none assessing measurement error (systematic and random error of a score that is not attributed to true changes) or cross-cultural validity (the performance of a translated or culturally adapted measure). Across most measures, internal consistency (the degree of inter-relatedness of items) was rated as unknown and content validity (whether the content is an adequate reflection of the construct to be measured) was rated as poor, although 6 measures had good content validity.

The measure with the strongest psychometric properties was the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire/Thwarted belongingness subscale (INQ-TB) which was developed in line with the interpersonal theory of suicide and was validated in a clinical sample (Van Orden KA. et al, 2012). The measure was rated as moderate or strong for internal consistency, structural validity (whether scores are an adequate reflection of the dimensionality of the construct to be measured) and criterion validity (whether scores are an adequate reflection of a ‘gold standard’) as well as good content validity.

Conceptual framework of social connectedness

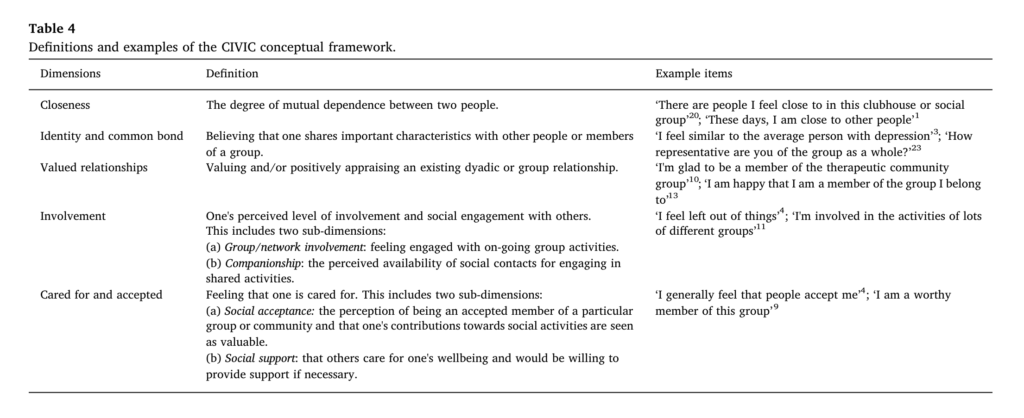

Five dimensions were identified by thematic synthesis of the items from all measures describing the experience of social connectedness:

- Closeness: the degree of mutual dependence between two people, e.g. ‘There are people I feel close to in this clubhouse or social group’.

- Identity and common bond: believing one shares important characteristics with other people, e.g. ‘I feel similar to the average person with depression’.

- Valued relationships: valuing and/or positively appraising an existing relationship, e.g. ‘I’m glad to be a member of the therapeutic community group’.

- Involvement: perceived level of involvement and social engagement with others, including group/network involvement and companionship, e.g. ‘I feel left out of things’.

- Cared for and accepted: feeling that one is cared for, including social acceptance and social support, e.g. ‘I generally feel that people accept me’.

The five CIVIC (acronym) dimensions were rated in two ways: specific or non-specific relationships. The former refers to feelings of connection to specific individuals or groups (e.g. therapy group), while the latter refers to perceptions about relationships or social experiences in general (e.g. community).

Through vote counting analysis, the most frequently assessed dimension across all measures was found to be:

- Identity and common bond,

- followed by Closeness,

- Involvement,

- Cared for and accepted

- and finally Valued relationships.

Four of the 21 measures were evaluated by the scale developers using factor analysis which identified only a single factor or component for each measure. However, these four measures covered more than one of the proposed dimensions in this review.

In sensitivity analysis, the items of the six measures which met COSMIN criteria for good content validity were reanalysed to test robustness of the synthesis. No marked differences were found between the sensitivity and primary analysis, and the same five dimensions of the CIVIC framework were identified.

Most measures of social connectedness have poor or unknown psychometric properties.

Conclusions

This review identified measures of social connectedness used in mental health service and summarised that most existing measures have poor or unknown psychometric properties.

The review also systematically conceptualised social connectedness and developed a five-dimension conceptual framework, including Closeness, Identity and common bond, Valued relationships, Involvement as well as Cared for and accepted. There is a dual rating of social connectedness within specific relationships and non-specific relationships in general. The authors concluded that the conceptual framework is relatively robust, considering the consistency of the identified dimensions across measures and within the sensitivity analysis.

A five-dimension conceptual framework of social connectedness was developed: CIVIC (Closeness, Identity and common bond, Valued relationships, Involvement, Cared for and accepted).

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this paper was the systematic approach taken to literature search, involving a pilot search to explore the appropriate text words and index terms. It is also good to see the paper present the complexity of its methodology well. The authors have reported their quality appraisal and data synthesis process in detail which enables the reader to follow their thinking. It’s impossible to include the results of all 21 measures or the detailed tables in this short blog, so if you are interested in social connectedness in the field of mental health, the full-text paper is well worth reading (if you can access it).

One limitation of the paper relates to the scope of the review. The authors developed the conceptual framework of social connectedness at an individual level rather than looking at its societal context such as participation in social, economic or political activity and social norms. Additionally, as the study participants must have a mental disorder to meet the inclusion criteria, measures potentially relevant to, but not used in the field of mental health may have been overlooked and the suitability for other population groups of reported measures remains unclear.

Another potential limitation relates to the search strategy. In order to focus the review on subjective, individual-level perceptions of relationships, some search terms were not used; for example terms which referred to resources provided within relationships such as social support. However, social support is a multi-domain concept which covers both practical and emotional support (Wang JY. et al, 2017). Actually, in the CIVIC conceptual framework developed by the authors, social support was included as one sub-domain of the ‘Cared for and accepted’ dimension.

The authors acknowledged that there may be generalisability issues across different socio-economic or cultural contexts. In addition, since at least 50% of the study sample needed to be 18-65 years of age according to the inclusion criteria, it is also unclear whether the results of this review can be generalised to older people and children or adolescents.

This is the first systematic review of conceptualisation and measurement of social connectedness in mental health service users.

Implications for practice

This review proposed a conceptual framework with five dimensions which fits existing measures of social connectedness. The authors recommended INQ-TB as a general measure for assessing social connectedness. However, the psychometric properties are not satisfactory for most included measures and the five-dimension CIVIC framework did not match the results of existing factor analysis for four of the included measures which identified only a unidimensional construct. Thus the development of new multi-domain measures covering all five CIVIC dimensions may be a useful focus for future research.

Like the authors of the paper reviewed here, I would love to see an improvement in clinical interventions to reduce feelings of loneliness among individuals with mental health problems. Conceptual clarity of social connectedness can support intervention development and evaluation. Complex interventions targeting multiple components may be more effective than those addressing only one dimension, e.g. social participation. The CIVIC framework may also help understand which aspects of people’s social relations are most problematic, and then consider individualised interventions. Nonetheless, we would need to be confident that interventions targeting dimensions of social connectedness will also effectively reduce loneliness. Although strong associations are found between loneliness and social connectedness, it does not mean that they are indeed equivalent.

Complex interventions targeting multiple dimensions of social connectedness may demonstrate greater effectiveness.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

Hare-Duke L, Dening T, de Oliveira D. et al (2018) Conceptual framework for social connectedness in mental disorders: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Journal of Affective Disorders 245: 188-99.

Other references

Haslam C, Cruwys T, Haslam SA. et al (2015) Social Connectedness and Health. In: Pachana N. (eds) Encyclopedia of Geropsychology. Springer, Singapore: 1-10.

Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL. et al (2012) Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Quality of Life Research 21(4): 651-7.

Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR. et al (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 60(1): 34-42.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A. et al (2006) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in sytematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme. London: Institute for Health Research.

Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK. et al (2012) Thwarted Belongingness and Perceived Burdensomeness: Construct Validity and Psychometric Properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment 24(1): 197-215.

Wang JY, Lloyd-Evans B, Giacco D. et al (2017) Social isolation in mental health: a conceptual and methodological review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 52(12): 1451-61.

Photo credits

- Photo by Ihor Malytskyi on Unsplash

- Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

- Photo by Elisa Michelet on Unsplash

- Photo by Dario Valenzuela on Unsplash

- Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash