Sexual minority individuals experience worse mental health outcomes compared to heterosexual people. This has been demonstrated in a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom whereby sexual minority individuals were more likely to experience depressive symptoms and report self-harm at an 11- and 5-year-follow-up, respectively (Irish et al., 2019). Such findings have prompted researchers to understand why higher mental illness prevalence occurs in sexual minorities.

Research has shown that sexual minority adolescents are almost three times more likely to experience childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, and peer victimisation (Friedman et al., 2011). Considering that childhood maltreatment has been demonstrated to increase the risk of developing various mental disorders, such as depression (Li et al., 2016), it appears plausible that childhood trauma and bullying victimisation could be potential contributors to the sexual orientation disparities in mental illnesses.

A recent study by Laura Baams and colleagues (2021) examined the mental health differences between sexual minorities and heterosexual individuals, subsequently seeing whether the sexual orientation mental illness disparity could be explained by childhood trauma and bullying victimisation.

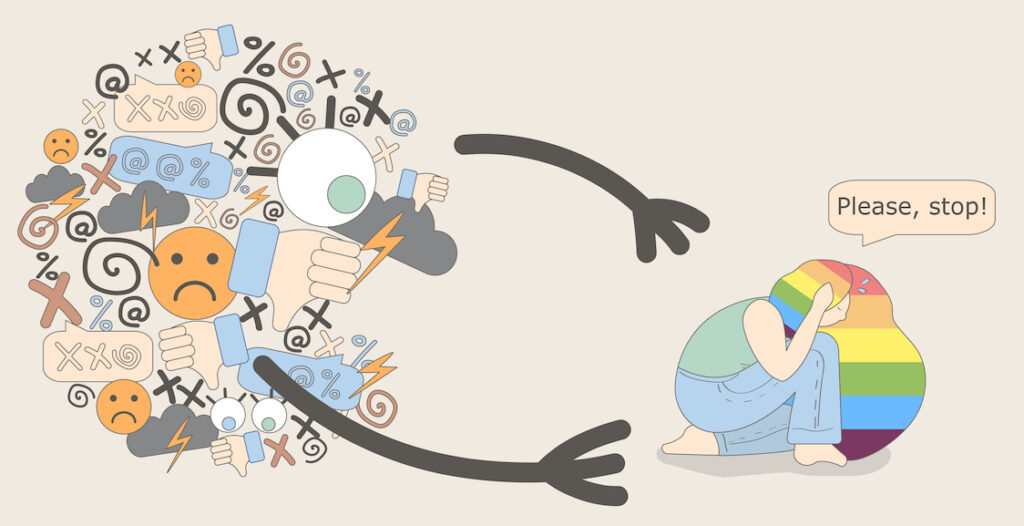

LGBTQ+ individuals are more likely to experience mental illness compared to heterosexual people. New research explores the role that trauma and bullying plays.

Methods

There were 6,393 participants in the study, with 44.9% identifying as male and the mean age being 44.2 years old. 91% of the participants reported being exclusively attracted to the other sex, and 6.5% said they were predominantly other sex attracted. The rest of the participants reported being either attracted exclusively or predominantly to the same sex or attracted to both sexes equally. They were referred to as the same/both-sex attracted group.

The following measures were used:

- The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 3.0 was used to examine lifetime and 12-month occurrence of DSM-IV disorders, such as major depression, generalised anxiety disorder, and substance abuse

- Childhood trauma was examined with a questionnaire created for the study. The questionnaire asked about the occurrence and the frequency of emotional, psychological, physical, and sexual abuse before 16

- Bullying-victimization was investigated with the following question: “Before turning 16 years old, were you bullied regularly?”

- Sexual orientation was examined with one question about sexual attraction: “Are you sexually attracted to men, women, or both?”

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate the differences by sexual attraction: i) in the occurrence and severity of childhood and ii) in the lifetime and 12-month occurrence of DSM-IV disorders. To explore whether bullying-victimisation and trauma severity explain these differences, childhood trauma and bullying-victimisation were added separately to the analyses when the difference by sexual attraction was significant. The indirect effect of childhood trauma severity and bullying-victimisation were also assessed. All the analyses controlled for age, gender, and education level.

Results

- Compared to exclusively other-sex attracted individuals, same/both-sex attracted individuals were more likely to experience all types of childhood trauma and bullying-victimisation and to have a higher childhood trauma severity score.

- Same/both-sex attracted individuals were also more likely to have lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV disorders, such as mood, anxiety and substance disorders than exclusively other-sex attracted individuals. However, no such differences were found between predominantly other-sex attracted and exclusively other-sex attracted individuals.

- Childhood trauma severity and bullying-victimisation explained between 9.0% and 57.0% and 6.6% and 26.8% of significant indirect associations between same/both-sex attraction and DSM-IV disorders, respectively.

Childhood trauma, bullying-victimisation, and DSM-IV disorders are more prevalent in sexual minority individuals.

Conclusions

This study highlighted that sexual minority individuals are at a higher risk of experiencing childhood trauma and bullying victimisation. It also suggests that this higher risk could explain the higher prevalence of DSM-IV disorders in this population, such as mood, anxiety and substance disorders.

These findings provide a potential explanation of the mental health disparities found in sexual minorities and underline the importance of providing appropriate and timely support and interventions to prevent mental health problems from developing.

These findings underline the importance of providing appropriate and timely support and interventions to prevent mental health problems from developing in LGBTQ+ individuals.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to examine whether childhood trauma and bullying-victimisation explain differences in DSM-IV disorders’ prevalence by sexual orientation. However, there are some downfalls of this study. Participants were asked to recall their experiences of childhood trauma and bullying-victimisation from below the age of 16. Individuals may have under- or overestimated the degree of maltreatment they experienced or felt reluctant to share these painful memories. Therefore, there is a chance these measurements were not entirely accurate.

Also, all the data was obtained from participants at one-time point, making it difficult to understand the directionality of the relationship between maltreatment and mental illness. There is a possibility that mental distress was present before the occurrence of childhood trauma and bullying victimisation.

Lastly, the study was based on a sample of adults from the Netherlands. The Netherlands was the first country to legalise same-sex marriage in 2001. Thus, the country provides a more accepting attitude towards sexual diversity than other Western countries and most non-Western countries. However, as social acceptance of sexual diversity varies among countries, it is likely that that the prevalence of childhood trauma, bullying-victimisation, and DSM-IV disorders in sexual minorities will vary as well. Moreover, the degree that negative childhood experiences explain mental health disorders in sexual minorities can also vary. Therefore, the current findings may not be generalisable to sexual minorities in other countries.

This study reflects insights from sexual minorities in the Netherlands, a country that legalised same-sex marriage in 2001 and has an accepting attitude towards sexual diversity. What about other Western and non-Western countries?

Implications for practice

These findings demonstrate that sexual minority individuals experience higher levels of mental distress compared to heterosexual individuals, so there is a need to ensure effective and accessible mental health care in this population. LGBTQ+ people have voiced their concerns about accessing mental health services; for example, some believe there is a lack of competence to provide LGBTQ+ affirmative care (Higgens et al., 2020). The NHS could introduce mandatory training for mental health practitioners on supporting sexual minorities to overcome this accessibility issue. During such training, it is essential to discuss intersectionality, specifically, how other aspects of a sexual minority individual’s life could contribute to mental distress, such as ethnic origin and cultural heritage.

It is also essential to address the root of the problem; this study demonstrates that childhood bullying victimisation and childhood trauma contribute to the sexual orientation mental health disparities. This highlights the importance of implementing anti-bullying campaigns in schools that explicitly recognise the needs of sexual minority students. Research has shown that schools that have implemented policies that prohibit bullying based on sexual orientation reported less bullying toward sexual minorities than schools that had no policies of this nature (Kull et al., 2016). Furthermore, LGBTQ+ identities must be discussed in PSE (personal and social education) and staff are provided with mandatory training on supporting sexual minorities experiencing mental distress.

We need LGBTQ+ affirmative education and health care.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Baams, L., Ten Have, M., de Graaf, R., & de Jonge, P. (2021). Childhood trauma and bullying-victimization as an explanation for differences in mental disorders by sexual orientation. Journal of psychiatric research, 137, 225-231.

Other references

Friedman, M. S., Marshal, M. P., Guadamuz, T. E., Wei, C., Wong, C. F., Saewyc, E. M., & Stall, R. (2011). A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. American Journal of Public Health, 101(8), 1481-1494.

Higgins, A., Downes, C., Murphy, R., Sharek, D., Begley, T., McCann, E., … & Doyle, L. (2021). LGBT+ young people’s perceptions of barriers to accessing mental health services in Ireland. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(1), 58-67.

Irish, M., Solmi, F., Mars, B., King, M., Lewis, G., Pearson, R. M., … & Lewis, G. (2019). Depression and self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood in sexual minorities compared with heterosexuals in the UK: A population-based cohort study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(2), 91-98.

Kull, R. M., Greytak, E. A., Kosciw, J. G., & Villenas, C. (2016). Effectiveness of school district antibullying policies in improving LGBT youths’ school climate. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(4), 407.

Li, M., D’arcy, C., & Meng, X. (2016). Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychological Medicine, 46(4), 717-730.

Photo credits

- Photo by Jordan Whitt on Unsplash

- Photo by Isaiah Rustad on Unsplash

- Photo by James A. Molnar on Unsplash

- Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash