If you had a serious mental illness, where would you want to be, in your own home or in a residential institution?

Researchers have published a new systematic review which compares the outcomes of living in independent housing and support settings versus institutionalised accommodation (Richter & Hoffmann, 2017).

Over the past few decades there has been a de-institutionalisation of mental health services in Western countries. For those with serious mental illness (SMI) this has led to a shift from being cared for in hospital settings to a less restrictive and more autonomous setting.

SMI is a pervasive and increasing problem amongst homeless populations. Around 70% of people accessing homelessness services have a mental health problem (Tomlin A., 2012).

Residential care for both homeless and non-homeless populations with SMI increasingly uses independent housing and support as opposed to institutionalised accommodation, but what do we mean by independent housing and support (IHS)? IHS is any kind of independent accommodation that is not supervised by staff on site, but where people with SMI are in receipt of professional support. For example, this could be their own flat or apartment or the family home.

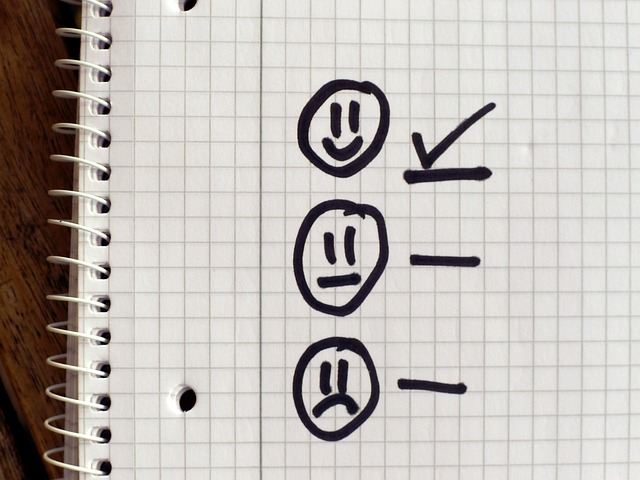

Independent housing is becoming increasingly more popular than institutions for people with serious mental illness.

Methods

The review incorporated randomised controlled trials and observational studies exploring various outcomes of IHS compared to institutionalised accommodation for both homeless and non-homeless populations with SMI (Richter & Hoffmann, 2017).

The reviewers assessed the risk of bias of each individual paper and then resolved differences by reaching consensus. They defined low risk of bias as well-conducted randomised controlled trials. Moderate risk was defined as well-conducted non-randomised comparative longitudinal studies or randomised controlled trials with some problems.

The study compared several different outcomes from IHS compared to other residential settings for homeless and non-homeless populations with SMI. They defined outcome domains as follows:

- Housing outcomes included factors such as housing stability and the number of days spent in one’s own apartment

- Social integration included community functioning, community integration, and physical and psychological integration

- Health status incorporated both mental and physical health, psychopathology, substance use, reoffending and healthcare utilisation

- Subjective assessment outcomes considered measures of quality of life, life skills, housing and life satisfaction, needs, choice, self-actualisation and recovery

- Finally, a small number of studies also compared costs in terms of treatment costs, housing costs and/or total costs.

Results

For the purposes of this review, homeless and non-homeless populations were reviewed separately due to significant differences in homeless populations. This includes clinical differences such as higher levels of addiction, differing social outcomes such as increased social exclusion and different challenges for housing placements for homeless people.

The review yielded 32 publications which fit the criteria. Of those, 24 studies focused on homeless populations including 20 randomised controlled trials and 4 observational studies. All but one of the RCTs were deemed to have low risk of bias.

Only 8 studies included non-homeless populations, all of which were observational studies with moderate or serious risk of bias.

Homeless

- Studies that measured housing outcomes were overwhelmingly in favour of independent housing and support (IHS)

- There were no significant differences between the two settings for social integration outcomes with three studies in favour of IHS and 9 not finding any significant differences

- Health outcomes overwhelmingly indicated no significant differences between the two settings with 16 RCTs and 2 observational studies finding no difference. However, 9 studies were in favour of IHS with no studies in favour of institutionalised accommodation

- Of the 6 studies exploring mental health and psychopathology outcomes, all found no significant differences between IHS and institutionalised accommodation

- Studies on subjective assessment outcomes found all studies to either be in favour of IHS or of no significant difference

- Only 3 studies considered cost with two in favour of IHS and one finding no significant difference.

Non-homeless

- None of the studies on non-homeless populations reported on housing outcomes or costs

- Two studies were in favour of IHS for social outcomes with one finding no significant difference

- There were no differences in health outcomes between the two settings

- There were no differences in subjective assessment outcomes for the two settings.

According to this review, housing outcomes are overwhelmingly in support of independent housing.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that IHS demonstrated better housing outcomes in homeless populations (according to randomised controlled trials). Most other conditions showed comparable results. IHS had no worse results than more institutionalised accommodation settings and did not achieve inferior results when compared to traditional residential settings.

The reviewers concluded that clients’ preferences should determine their accommodation setting in the first instance, even when professional expertise suggests otherwise.

They proposed that they will establish a set of principles, as well as a label, which refers to the main goals of independent living for people with SMI.

This review suggests that people with serious mental illness should decide their own preferred accommodation setting.

Strengths and limitations

As acknowledged by the authors, the intervention settings and the control settings were poorly defined. There is an apparent lack of clarity and focus around what constitutes IHS as opposed to institutionalised residential care. This is particularly prominent in IHS settings that reflect a wide scope of service provisions. There is no usual standard of care for these services, therefore there may be wide ranges of staffing ratios, multi-disciplinary professionals, and non-health related support provided. This is a particularly prominent issue for homeless populations as they are more likely to require support with managing tenancies, budgeting, independent living skills and substance misuse.

Some outcomes only include a very small number of studies, which make it difficult to reach a substantive conclusion. Further to this, some of the factors grouped together do not have an obvious link to the outcome domain. For example, reoffending was included in the health status outcome domain, whereas this may have more obvious links to social integration outcome domains.

There is an apparent lack of clarity and focus around what constitutes independent housing and support (IHS) as opposed to institutionalised residential care.

Implications for practice

The findings of the review are limited in their applicability. There are large geographical variations in service provision, particularly in relation to IHS. Even projects in the same locality may be subject to different contractual agreements with differing outcome goals. The lack of clarity and ambiguity in what constitutes an IHS service makes it very difficult to draw firm conclusions.

Despite this the initial scope of evidence suggests that IHS provides at least similar, if not better, outcomes for homeless populations, particularly in relation to housing outcomes. It is worth considering that with independent housing comes the risk that those in need of support “fall through the net” of local services and can quickly become isolated, without support and at risk of losing their accommodation or experiencing a mental health crisis. Those in independent houses have more opportunity to avoid engagement if they choose to, therefore not receiving the support they need to maintain their mental health and their home.

IHS services have potential to produce outcomes that are not just comparable but exceed those of institutional accommodation. At present, funding for IHS services is short term and insecure, as in many localities services such as these remain “pilot” services in the absence of more substantial and empirical evidence to support the commissioning of such services. Institutional accommodation has existed for many decades whereas the IHS is still a novel approach, as such, IHS services have not had an opportunity to become established and refine their models. There are also pervasive attitudinal barriers of existing service providers, commissioners and private landlords, particularly for those who are homeless, with regards to being unable to maintain tenancies, anti-social behaviours, and substance misuse.

IHS settings have great potential to improve outcomes for both homeless and non-homeless populations with serious mental illness and provide a competitive alternative to institutional accommodation. However, for such services to be successful, service models need to be refined to promote best practice and improve outcomes. It is essential that there is high quality, flexible, multi-disciplinary support that needs to be well co-ordinated with an appointed person such as a professional lead, care co-ordinator or single point of contact for the individual.

Independent housing and support has great potential to improve outcomes for both homeless and non-homeless populations with serious mental illness and provide a competitive alternative to institutional accommodation.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Links

Primary paper

Richter D, Hoffmann H. (2017) Independent housing and support for people with severe mental illness: systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017: 1–11 DOI: 10.1111/acps.12765 [PubMed abstract]

Other references

Tomlin A. New NHS Confederation briefing on homelessness and mental health. The Mental Elf, 12 April 2012.

[…] Independent housing and support for people with severe mental illness […]

[…] Independent housing and support for people with severe mental illness https://www.nationalelfservice.net/populations-and-settings/housing/independent-housing-and-support/… […]

Dear Sophie,

as the first author of the source publication I would like to thank you for the summary and the conclusions. We are currently working furhter on this issue and we will be starting an RCT on IHS later this year.

People who are interested for further information can contact me at dirk.richter@upd.unibe.ch.

Regards,

Dirk Richter