What would we do if one of our Elf family were to find themselves at a point of crisis; a mental health crisis? Well, the National Health Service (NHS) Mandate for 2014/15 stated that services for patients in mental health crisis should be as accessible, responsive and high quality as emergency services for other patients…but, is that currently the case? There are frequent media reports in relation to increasing mental health demand and a potential shortage of resources to meet this, so what is actually happening?

Liaison Psychiatry Services across the country often see patients who have attended an Emergency Department (ED); sometimes because there are literally no other (or better) places to go to get help. Working within a Liaison Service this feels like common knowledge, and I have personally often quoted the well worn statistic of 5% of ED attendances are mental health related. What might not be common knowledge though is that this statistic is based on an American sample of Medicare patients from 1999; and only factored in depression. Surely we must have more up to date, UK based research from which to base service developments and commissioning?

This is exactly what Barratt et al wanted to look at by publishing their systematic review and meta-analysis looking at the epidemiology of mental health-related ED attendances within health care systems free at the point of access, including clinical reason for presentation, previous service use, and patient socio-demographic characteristics. This was then published in PLoS ONE on April 27, 2016.

The NHS Mandate states that people in mental health crisis should have access to a responsive, high quality emergency service.

Methods

Electronic database searches were completed across Embase, Medline, PreMedline, PsycINFO and CINAHL. The inclusion criteria for the studies were:

- Describing services in the UK, the rest of Western Europe, Canada, or Australasia (as these were considered most comparable to the English NHS, where care is free at the point of use);

- Describing a cohort, case-control, cross-sectional or ecological study; and

- Relating to patients aged 18 or over.

They employed a text mining and machine learning method, known as ‘active learning’, The primary goal of text mining was to retrieve information from unstructured text and to present the distilled knowledge to users in a concise form. The machine learned iteratively (from human interaction) to distinguish between relevant, and irrelevant citations during the screening phase of the systematic review. Not something I have come across previously, but not necessarily a reason in itself to be skeptical.

The process searched for studies describing patients who attended a hospital ED with a primary diagnosis of either one of more mental and behavioural disorders (F01-F79 of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition) or self-harm (X60-X84). Studies also had to report one or more epidemiological measure, for example the frequency, incidence, occurrence, or prevalence of mental health-related attendances to the ED. Heterogeneity was also estimated using the I2 statistic, where I2 > 50% this was considered substantial heterogeneity. I was hopeful that this would produce a wealth of results to look at.

Results

The original database search produced over 16,000 results. Manual screening was truncated at 6,500 and 6,296 records excluded at this time. 97 were then excluded due to being ineligible countries or populations, leaving 107. On the final exclusion round 89 were excluded; 57 due to being focused on self-harm, attempted suicide or overdose, 3 were excluded as they were to do with a specific mental health condition and 29 were excluded due to being about alcohol or illicit drug use.

This left only 18 studies which met the eligibility criteria, 6 of which were used in the meta-analysis (a disappointing 0.1% of the original results).

Nine studies were conducted in Australia; three in Spain; two in Canada and one in each of the UK, Ireland, Norway and Portugal. Studies took place largely within single emergency departments (n = 14). Five examined attendances to dedicated psychiatric EDs, rather than general departments.

The studies differed in the data they reported: whether in terms of total ED attendances, or in terms of individual patients who may potentially have made multiple attendances. Eight reported only attendances; six reported only patients; and four described both types of data. Sample size varied from 168 to 290,606 ED episodes and 36 to 3,853 individual patients.

3 were deemed as good quality, 10 fair and 5 poor. The generalisability of the findings was assessed as poor in 15/18 studies, usually because the study described a relatively small sample from a single hospital site. This makes the actual results rather meaningless, however, here they are:

Proportion of ED attendances related to mental or behavioural health disorders:

Estimated as 0.04 (95% CI, 0.03 to 0.04), or 4% of ED attendances.

Of those patients presenting with MH disorders:

Clinical reason for attendance (with 95% CI)

- Suicide risk / attempt; 9% [0.05 to 0.14]

- I2 0%

- Self-harm; 27% [0.210 to 0.326]

- I2 87.1%

- Schizophrenia; 6% [0.045 to 0.066]

- I2 0.4%

- Depression; 13%[0.101 to 0.170]

- I2 76.7%

Previous service use

In the UK study 58.1% of attendees had a previous history of mental illness.

Individual patient characteristics

Age: there was insufficient data available to carry out meta-analysis.

Gender: 50% of attendances were by women (95% CI 0.45 to 0.55, I2= 7.3%).

Socioeconomic circumstances: 53% of patients attending an ED in London, were unemployed in contrast to 83% of frequent attendees at an ED in Galway, Ireland. In London, 17% were of no fixed abode, whilst 4% of patients attending EDs in Victoria, Australia, were resident in crisis accommodation at the time; the same proportion were deemed to have no shelter. 45% of frequent attenders to a dedicated psychiatric ED in Montreal, Canada were in receipt of welfare payments.

Destination on discharge

Up to 58% were admitted, although not all studies described what type of admission that was and there was not enough data to be able to use meta-analysis to calculate meaningful pooled estimates.

Broken down by type of ward, the proportion of patients admitted to a mental health unit ranged from 8% to 27.8%, whilst the proportion admitted to a general medical ward ranged from 6.6% to 16.7%.

There were varying data as to the percentage of community or GP follow up, however, within these papers, it was only clear in one case that the discharged patient did not receive any form of follow up.

Authors Conclusions

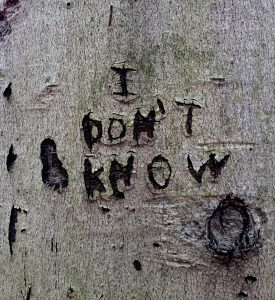

The review strongly suggests that there is a lack of high quality, generalisable epidemiological data available to inform service change and the development of new models of care.

The main recommendation from the paper is that prevalence studies of mental health-related ED attendances are required to enable the development of services to meet specific needs, particularly in the UK.

This research highlights just how little we know about the prevalence of mental illness in emergency departments.

Strengths and limitations

The data that is available must be interpreted with extreme caution. Particularly in light of issues relating to the quality of the data reported; the overall methodological quality of the studies; and the generalisability of the study findings to other services and local populations. The most important causes of variability related to differences in either clinical or methodological aspects of the research looked at, and the fact that so few studies were included.

The process of exclusion/inclusion of the papers appeared too stringent; for example specifically excluding papers which focussed on self harm, attempted suicide or overdose, would seem to have missed an opportunity to capture some of that epidemiological data.

Summary

From this systematic review and meta-analysis the number of patients attending due to mental or behavioural health disorders accounted for 4% of ED attendances; a third of these were due to self harm or suicidal ideation. The majority of studies were single site and of low quality and with so few papers included, the results need to be interpreted very carefully. I was really surprised that there was only one study which was conducted in the UK and this was assessed to be of poor quality. As my teacher might say “tsk tsk – must do better”.

From my own personal experience, patients are presenting at ED with mental health problems, and will carry on doing so with or without Liaison being there. We must address this gap in knowledge and understanding of presentations as a matter of urgency.

Links

Primary paper

Barratt H, Rojas-García A, Clarke K, Moore A, Whittington C, Stockton S, et al. (2016) Epidemiology of Mental Health Attendances at Emergency Departments: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 11(4): e0154449. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154449

@Mental_Elf fascinating blog @LiaisonLawson & good point about missed opportunity re O/D presentations

@ian_hamilton_ @Mental_Elf such a shame to pass up the opportunity to use the evidence that is actually out there

@LiaisonLawson @Mental_Elf yes & likely to be substantial number who have substance use & MH problems that result in presentations…

@ian_hamilton_ @Mental_Elf absolutely!

Today @LiaisonLawson on the epidemiology of mental health attendances at emergency departments https://t.co/WLGxPPAUf0

It’s very valuable to have this review, thank you.

In the PHE/NHSE Mental Health Intelligence network we have a programme on Crisis data metrics. This seeks to map, for each of the 27 agencies that form the crisis concordat partners, the data currently collected and how to achieve better, consistent, aligned routine metrics collection for all crisis services. This will enable us to understand who are people( age, gender, ethnicity etc) that present to all crisis type service, when they present across 24/7, the proportion that are new/ known/ frequent attenders, why they have a crisis i.e. has it been triggered by social, mental ill health, ‘behavioural’, trauma, and other factors & could a prevention strategy lead to a reduction in the causes of crises. We would value a discussion with others working in services and internationally, developing comparable metrics

Hi Geraldine. Happy to be involved – from a Kent/Liaison perspective.

People in mental health #crisis should have access to a responsive, high quality emergency service, but do they? https://t.co/WLGxPPAUf0

.@Mental_Elf From experience, no. “Could get MH team but I won’t. Go on youtube, find some videos on drawing, get some pencils” Not kidding

@Mental_Elf As always, it’s a postcode lottery! @RCNMHForum

@Mental_Elf Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha. That’ll be a ‘no’.

@Mental_Elf Disappointed but not surprised at lack of data on how MH system treats patients (start to finish) rather than solely diagnoses.

@Mental_Elf no. End of

RT @Mental_Elf: Systematic review highlights just how little we know about prevalence of mental illness in emergency departments https://t.…

Uncertainty highlighted in recent SR about epidemiology of #MentalHealth attendances at #Emergency departments https://t.co/WLGxPPAUf0

Don’t miss: Why don’t we know more about mental health presentations in A&E departments? https://t.co/WLGxPPAUf0 #EBP

@Mental_Elf bcos they think ur a time waster n just want 2 treat ppl w ‘proper’ problems that arent there ‘fault’

@Mental_Elf Is the answer “Because ED consultants don’t want us there & the general public doesn’t care about #mentalhealth folks”?

@Mental_Elf nice piece! Timely too!

Good piece! Difficulty with data might be due to who describes presentation. In my ED attendees are clerked in by admin staff who identify why attending. By the time they are triaged the p.c is sleazy on the system. Presenting complaint and diagnosis at point of dx may be different!

Most popular blog this week? @LiaisonLawson Do ppl in #MentalHealth #Crisis get high quality emergency services? https://t.co/WLGxPPAUf0

[…] How much mental health presents in emergency departments? We don’t really know. […]