The Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA) regulates when people can be involuntarily detained in hospital on psychiatric grounds in England and Wales. It was most recently reviewed in 2007 but since then the rate of its use (per 100,000 population in England) has risen rapidly. However, it isn’t clear why this is or whether it is, at least in part, because of changes resulting from the 2007 review.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) publish an annual review of how the MHA is being used (Monitoring the Mental Health Act). In their 2016/2017 publication they said that there is no single cause for the rise, but they suggest several factors that could be playing a role:

- It appears that more people are being subject to the MHA, rather than the same people being detained multiple times.

- Psychiatric bed numbers have fallen and more people with severe mental health problems are living outside of a hospital setting. As such, there will be more admissions and so a greater risk of being detained.

- Clinicians are applying the criteria for detention differently to people with certain types of disorder (such as dementia or personality disorder), so some people are being detained under the MHA who would previously not have been.

- It may be that more people with mental health problems are coming to the attention of mental healthcare workers (for example, through schemes that divert people from the criminal justice system).

- It may be that people are increasingly likely to refuse voluntary admission, perhaps because wards are becoming more unpleasant places to be (Keown et al. 2011), and so are being admitted formally.

- It may be a proportion of detentions could have been prevented if less coercive alternatives in the community were available.

- It may be that there have been demographic or socioeconomic changes, such as greater economic deprivation, which have resulted in vulnerable groups being at higher risk of developing more severe psychiatric illnesses.

- Finally, some of the rise may be due to problems in the data collection, such as an increase in duplicate returns.

There is currently a review of the MHA underway, which is partly due to concerns about this rise in rates in involuntary hospitalisation as well as the continued overrepresentation of certain groups, particularly young men from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. Amongst other things, it aims to consider what can be done to reduce inappropriate uses of the MHA and improve how services respond to people in crisis. The final report is expected in the coming months, and an interim report was published in May 2018.

In this blog I summarise a recent and timely paper by Keown et al. (2018) that breaks down the MHA data and discusses some possible explanations for the rise.

Psychiatric bed numbers have fallen and more people with severe mental health problems are living in the community, so we should expect more admissions and a greater risk of being detained.

Methods

The authors obtained data on involuntary hospitalisations for each year between 1984/1985 and 2015/2016 and calculated rates per 100,000 population using population data for England. They looked at uses of both civil (Part II of the MHA, issued in the community or hospitals) and forensic sections (Part III, issued by courts or prisons), and included uses in public and private hospitals. They only included uses of sections that permitted detention for 28 days or longer. They included instances where the patient was admitted on a longer-term section (e.g. section 2 or s.3), where they were admitted on a shorter-term section (e.g. s.4) and subsequently converted, and instances where the patient was admitted voluntarily and subsequently placed under one of the longer-term sections. Shorter-term sections (e.g. s.136 or s.4) and informal admissions were excluded unless they were subsequently converted. Involuntary detentions on admission included revocations of community treatment orders (CTOs), but not recalls. Data on uses of the MHA were obtained from NHS Digital and the National Archives. Not all data were available for the whole period, which is covered in the limitations section below.

Results

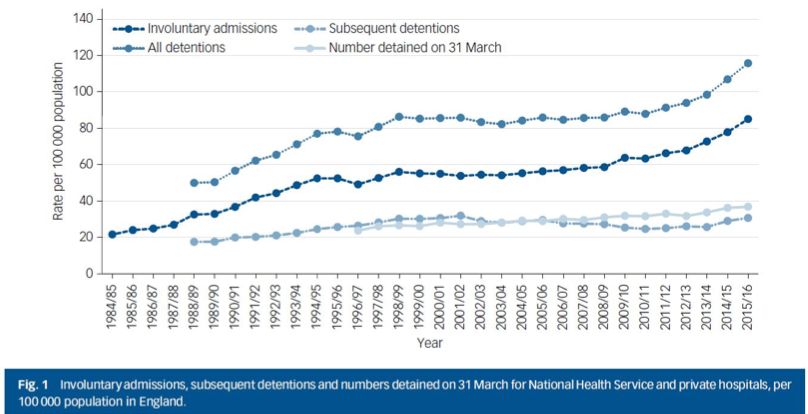

- The overall rate of involuntary hospitalisations rose from 50 per 100,000 in 1988 to 115.7 in 2015/16, a more than two-fold increase (131%) over 28 years. The greatest rate of increase occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, but there has been a second period of rapid increase since 2008.

- The rate of sections on admission rose from 21.5 per 100,000 in 1984/1985 to 85.0 per 100,000 in 2015/16, an almost four-fold increase (295%) over the 32-year period, and the rate increased in 25 out of those years.

- The rate of sections following informal admission increased from 17.5 in 1988 to 30.7 in 2015/6. The total number of patients in hospital who were on section (based on figures for the 31st March of each year) also increased from 11,500 (23.7 per 100 000) in 1997 to 20,151 (36.8 per 100,000) in 2016.

- While the rate of civil sections on admission increased from 19.0 per 100,000 in 1984 to 81.9 per 100,000 in 2015/16, the rate of forensic sections on admission rose initially from 2.5 in 1984 to 4.7 in 1993/94, then fluctuated with a slow overall decline to a rate of 3.1 in 2015/16.

- Between 1984 and 2015/2016, the proportion of sections on admission in private hospitals rose from 3% to 15% (odds ratio (OR) = 5.20, 95% CI 5.18 to 5.22). Although there was an increase for civil sections over this period (OR = 4.93, 95% CI 4.91 to 4.95), forensic sections showed a great rise from 2% to 20% (OR = 11.58, 95% CI = 11.48 to 11.72).

Figure 1 reproduced from Keown et al, 2018. See full size version.

Conclusions

Since the introduction of the MHA 1983, the rate of involuntary hospitalisation has approximately doubled. The last 10 years has seen a particularly rapid increase in this rate. Civil sections account for the majority of uses of the MHA overall, and the rapid rise in the involuntary hospitalisation rate since 2008 is attributable to a rise in uses of civil sections much more than forensic ones.

Secondly, given the significant rise in the number of people on section (from 23.7 per 100,000 in 1997 to 36.8 per 100,000 in 2016), the increase in the rate of involuntary hospitalisation is at least partially attributable to more people being subject to the MHA.

Finally, although the substantial majority of involuntary hospitalisations still occur in NHS hospitals, there has been a large increase in the number occurring in privately provided care. This, the authors suggest, may be partially the result of a drastic reduction in the number of NHS inpatient mental illness and intellectual disability beds, while the number of involuntary hospitalisations has risen (this has also been discussed in Keown et al. 2011). However, they also point out that this can’t be the whole explanation as the number of forensic sections has risen in the private sector but has remained stable overall. Meanwhile there has been an increase in the number of forensic beds in both the NHS and the private sector. This, as they say, is worthy of further research.

The authors also note that this rise in involuntary hospitalisation has occurred while the provision of community services have also increased ‘beyond recognition’. They say that, clearly, there is a requirement for inpatient treatment that community-based treatment cannot be substitute for.

Why rates have risen is not clear. The authors suggest several explanations:

- The development of community services may have improved their accessibility to patients as well as led to more assertive follow-up arrangements, and thereby improved the detection of severe mental illnesses.

- More patients are now treated primarily in the community than previously, at least in part due to there being fewer hospital beds. However, it may be that treatment in some cases can be delivered more effectively and more safely in hospital, particularly for individuals with limited social support. This would lead to greater rates of readmission to hospital, which may necessitate detention at the point of readmission.

- Equally, it may be that clinicians are using the MHA to manage risks, particularly when community-based treatment is difficult to deliver safely. Fragmentation of services may lead to a lower tolerance of risk as clinicians have less established therapeutic relationships, leading to clinicians being less able to encourage voluntary admission.

- Legislative changes, particularly the introduction of the Mental Capacity Act in 2005 and amendments to the MHA in 2007, have resulted in patients who are not objecting but who lack capacity being detained, where previously they would have been treated in hospital on a voluntary admission.

- Finally, many social services departments have developed teams focused on assessing patients under the MHA and, if justified, detaining them.

The number of forensic sections has risen in the private sector, but has remained stable overall.

Strengths and limitations

This recent paper is one of a relatively small number to examine the figures regarding rates of involuntary hospitalisation, and it gives some potential explanations for the rise. It provides an important and topical reflection on the rising rates of involuntary hospitalisation, but it notes that further research is needed to explore the causes.

As stated by the authors, a limitation of the paper is that the data are from routinely collected sources and this introduces some difficulties:

- Firstly, some parts of the data-set were not reported for the whole period since 1984:

- Data regarding detentions subsequent to voluntary admission were only available from 1988 onwards for NHS hospitals, and from 2000 for private hospitals.

- Detention in hospital following section 4 or police holding powers (Section 136) data were available for the NHS from 1988, and from 2006 for private hospitals.

- Secondly, there was a small dip in the figures in 1996/7 due to a switch to the KP90 data collection, but the previous trend of increasing numbers of detentions resumed the following year.

This research provides an important and topical reflection on the rising rates of involuntary hospitalisation.

Implications for practice

In the authors’ opinion, the results of the paper indicate that legislative reform of the MHA is as likely to lead to more detentions as it is to lead to fewer. The experience since 2008 in England is that any legislation that is driven by concerns relating to mental capacity, may risk leading to increasing rates of detention, particularly among those with dementia. This has consequences for patients and families and is also likely to put further financial strain on local authorities.

Will further reform of the Mental Health Act lead to more or fewer detentions?

Conflicts of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

Keown P, Murphy H, McKenna D, McKinnon I. (2018) Changes in the use of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England 1984/85 to 2015/16. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(4), 595-599. doi:10.1192/bjp.2018.123

Other references

Care Quality Commission (CQC) Monitoring the Mental Health Act report.

Keown P, Weich S, Bhui KS, Scott J. (2011) Association between provision of mental illness beds and rate of involuntary admissions in the NHS in England 1988-2008: ecological study. BMJ 2011; 343 :d3736

The independent review of the Mental Health Act – Interim report.

Photo credits

- Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

- Photo by Adhy Savala on Unsplash

- Photo by Jack Finnigan on Unsplash

- Photo by Serrah Galos on Unsplash

- Photo by Franzie Allen Miranda on Unsplash

So a rapid increase in the 80s and 90s as asylums closed and again post 2008 as services, both inpatient and community, cut for most seriously ill, complex and hard to reach? Would have been really something if rates had gone down over these periods

I signed my first section as a Mental Welfare Officer (the AMHP’s predecessor) in 1971; was team leader of the first modern community mental health team in 1977; deputy lead for BASW in the review of the 1959 MHA; one of the first members of the Mental Health Act Commission (MHAC) in 1983; and BASW’s lead on the 2007 amendments to the 1983 Act. I think there are at least 9 reasons for the steady rise in detention since 1983:

1. Reduction in de facto detention due to MHAC regulation after 1983 – we would visit large hospitals where virtually nobody was detained but notes said “section if attempts to leave”

2. Realisation that the 83 Act conferred significant rights – second opinions and Legal Aid for tribunals

3. Reduced “institutionalised compliance” and acceptance of professional authority

4. Huge increase, from late 1980s on, in use of illicit drugs making patients less co-operative and more unpredictable

5. Expanded community services identifying more people in need of treatment and treating them more pro-actively

6. Earlier discharges, encouraged by use of depot medication, some of which were inevitably too early (but also recognition that frequent short spells in hospital might still offer a better quality of life overall than long-term preventive institutionalisation)

7. Routine locking of acute wards (almost unknown in the 1980s)

8. Bed scarcity meaning delays in admission (and deterioration in mental state whilst waiting), increased use of out-of-area hospitals, plus priority for patients on section (in the 1970s and 80s we could usually readmit existing patients informally at the first sign of deterioration, to the local ward with which they were already familiar)

9. Realisation (still very patchy) that the MHA must be interpreted in the light of the Human Rights Act, and that the “acid test” for deprivation of liberty is therefore now the threshold for detention.

Just to extend Jo’s point, Martin Webber has pointed out when blogging about this research that there appears to be a direct relationship between the years in which a Conservative government is in power (numbers detained rose throughout the years 83-98, 2008-present) and when a Labour government was in power (numbers appear broadly constant between 1999-2010).

The period during the first decade of this century coincided with the publication of the Mental Health Implementation Plan, and the development of Crisis Resolution/Home Treatment Teams, Early Intervention Teams and Assertive Outreach Teams.

I’m not trying to argue that these services were without their problems, but it represents a time when additional resources were being allocated to mental health services in the community.

Perhaps the authors of the study either did not recognise this co-incidence, or felt it was too party-political to include in their analysis.

[…] Mental Health Act detentions are increasing, but why? […]