Two years ago I was a carer for three people – my daughter who has profound and multiple disabilities, my mother who is physically disabled and my father who had dementia. This month marks two years since my father died and it seemed fitting to be reviewing an article focused on dementia and reflect on how we made decisions for my father as he lost the capacity to do so for himself.

The article highlights how as carers we defer the more difficult and long term decisions until the person who has dementia cannot make or contribute to them, thus removing some of the autonomy which many of us believe to be important.

The article focuses on a study carried out in the north of England with male carers of people who have dementia. The study, using in-depth interviews, analyses how male carers make decisions – differentiating between day-to-day decisions, medium term decisions and long-term decisions.

The authors argue that most research and debate focuses on the rights of people with dementia within health care and care settings, for example the use of GPS tracking devices, restraint and medical research.

This study focused on more ‘nitty-gritty’ decisions that enable people with dementia to live their lives. The researchers were interested in how the rights to autonomy and decision making were exercised.

The research looked at decision making in a small sample of male carers for people with dementia

Method

The study is a relatively small one which interviewed nine male carers of people with dementia living in a large city in the north of England. All the males provided care to women, mainly their wives. The majority were living at home or independently.

Carers were asked to describe a typical day as well as the types of, and ways in which decisions were made.

The data gathered from the interviews was analysed in an attempt to identify themes. The analysis focused on two themes.

First, it looked at how the carers managed their caring role and duties and within this the activities which gave opportunities for autonomy.

Second the researchers addressed how the carers reflect on and evaluate their anxieties about caring as well as their decision making.

Carers were asked to describe the ways they made decisions for the short, medium and long term

Findings

All the participants described the gradual process they went through from husband/son/nephew to care-giver. They all saw caring as an act of loyalty or duty. For most of the men becoming a carer meant taking on new tasks.

The research differentiates between decisions which were sited in two different contexts:

- Those that relate to the more controllable task-driven decisions (for example household chores). Many of the men managed by feeling a sense of satisfaction in keeping control and carrying out these tasks and making the decisions relating them.

- Those that related to the uncontrollable fear-driven aspects of caring (for example, wandering). Carers would manage these aspects by trying to anticipate behaviours and take steps to stop them occurring (for example, locking doors).

In terms of time, the researchers were interested in three types of decisions:

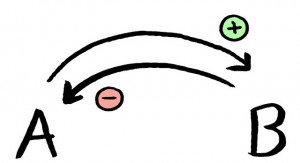

- Day to day decisions (for example, what to eat, wear or do) – carers described the slow progression from shared decision making to taking over making the decisions. Some of the carers described encouraging the person to make the decision for themselves as a way of trying to maintain their cognitive abilities.

- Medium term decisions (whether or where to go on holiday) – carers would often encourage the person with dementia to help make these decisions, but they were often deferred and ultimately made by the carer

- Long term decisions (care home provision) – most of the carers stated that these decisions were never discussed and described how these decisions would be made based upon their knowledge of and shared experiences with the person with dementia.

The researchers have attempted to understand and explain the way in which decisions were made by using the concept of ‘practised autonomy’. They state that the carers used ‘practised autonomy’ to ‘negotiate the uncertain and fluid circumstances they, and those they care for, find themselves in’ (p.11).

Caring is an ongoing process which starts with reciprocity and mutual decision making and as time progresses and the care-receiver becomes more dependent so the capacity for those two qualities diminishes.

Many of the decisions made by carers were influenced by the level of control they felt in the particular situation. As one would expect they felt more control over the task-driven aspects of caring and decision making was encouraged or shared.

Whereas the carers felt less in control in the fear-driven tasks and tended to make decisions by reflective evaluation – a two-staged process. First, the carer would anticipate the wants, needs and behaviours of the care-receiver based on past shared experience, then a decision would be made on the basis of whether or not it made life easier for them, avoided embarrassing or harmful situations or the decision would be deferred until a time when the carer had no choice but to make the decision.

Within this situation carers were aware that they were denying the person they cared for the right to contribute to decision making. But they believed that they were doing this in a compassionate way which took into account the needs of the care-receiver. Thus the process of practised autonomy was driven by a desire to do what was best for the person with dementia and for themselves.

Decisions were made using the concept of ‘practiced autonomy’ to negotiate uncertain circumstances and do the best for the person with dementia.

Conclusion

The study explores the ways in which decisions are made by male carers caring for people with dementia. The findings suggest that the way in which decision making takes place reflects the way in which carers try to manage and control their caring tasks – both task-driven and fear-driven aspects of caring.

Initially there is greater mutual decision making, particularly in relation to day-to-day task-driven decisions. This decreases as the dementia progresses and is also less evident in fear-driven decisions and long-term decisions which are often deferred until such time as they will be made by the carer.

Strengths and limitations

The limitations of this study are acknowledged by the researchers – it is a small study which makes generalisation difficult. However, the nuances and quality captured in the quotes from the carers gives the article richness and value. In addition as most of the male carers were providing care to their wives. Thus the findings may offer limited insight in non-heterosexual relationships.

The researchers used the concept of ‘practised autonomy’ to explain their findings. However it is not a term which is readily understood and could have been explained more clearly in order to understand the findings.

Summing up

Although this is a small study based on the experience of nine male carers I found that much of what was described had resonance for me as I reflected on the caring role I had for my father who had dementia during the last 10 years of his life.

Autonomy in decision making, in my experience does decrease as the condition progresses and it is influenced by the types of decisions and whether or not they are immediate or long term decisions.

As a carer who believes strongly in giving those that use services greater choice and control this study enables a better understanding of what that means for people with dementia and their carers.

Autonomy in decision making may decrease as dementia progresses and can depend on whether decisions are immediate or longer term.

Link

Sampson, M.S and Clark, A. (2015) ‘Deferred or chickened out?’ Decision making among male carers of people with dementia. Dementia, 8 January, pp.1 – 17 DOI: 10.1177/1471301214566663 [Abstract]

Photo Credits

Today @JeanneCarlin reflects on her own experiences as she looks at a study on #carer decision making & autonomy https://t.co/MFJMxLs4qA

Controllable tasks, uncontrollable fear: Decision making in male carers of people with #dementia https://t.co/JlIectKR3b @CarersTrust

‘Practiced autonomy’ & #carer decision in #dementia: @JeanneCarlin explores research & her experience https://t.co/YNz5KXPz9C @alzheimerssoc

RT @SocialCareElf: Don’t miss: Decision making among male carers of people with dementia https://t.co/lWTSyiANRG #EBP