Autonomy is defined as the freedom to determine one’s own actions or behaviour. It is a value at the heart of health and social care support and those supporting people with learning disabilities are constantly striving to maintain and indeed increase the autonomy of those they provide help to.

The authors of this Netherlands based study were interested in exploring how this works out in practice in relation to end of life care, a time when most people will face increasing challenges to their personal autonomy as they may become increasingly dependent on others.

The authors were interested in exploring how caregivers and relatives shape respect for autonomy in the end-of-life care for people with learning disabilities who may have been in situations of dependence on others throughout their lives. Challenges relating to communication may mean that it may not be entirely apparent what the end of life wishes of the person are. In this context the liberal notion of autonomy may not serve people well and the authors point out that in care ethics a relational conception of autonomy might be more helpful, where notions of interdependence begin to replace dependence or independence as a way of thinking about the human condition.

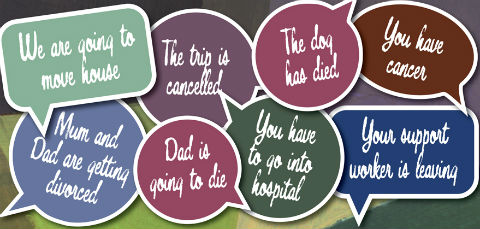

The authors were unable to find any studies addressing respect for the autonomy of people with learning disabilities in relation to end-of-life care, although there are a number of studies looking at truth-telling, the involvement of people with learning disabilities in decision-making and life preferences. In particular we posted last year about the development of guidelines regarding breaking bad news, where the authors identified that whilst there may be valid reasons why people with learning disabilities have been protected from the truth in bad news situations, it is important to assess whether non-disclosure is always in the individual’s best interest and that this position needed to be constantly re-assessed over time.

Guidelines on breaking bad news suggest constant reassessment of decision not to disclose

Method

The researchers used semi structured interviews with 47 professional caregivers and relatives across 10 provider organisations in the Netherlands to explore the circumstances surrounding the recent deaths of 12 people with learning disabilities supported in those agencies.

In terms of the 12 people with learning disabilities, there were six men and six women with different levels of severity of learning disability. For half the group, the cause of death was cancer. Half the group died in their own home, two in an intensive care unit of their care provider, three in a hospital and one in a hospice.

In relation to when participants were aware that the death of the person was imminent, responses to this ranged from 2 days to 6 months before the death occurred.

The authors identified themes from the transcripts of the interviews and validated their results in discussions with two focus groups of caregivers, trainers and policy experts.

Findings

What they found was that respect for autonomy became apparent at three kinds of transitions at the end of life:

- when new information became available about diagnosis, prognosis or treatment

- when care needs and wishes of the person changed

- when important decisions needed to be made.

They found that for caregivers and relatives, respect for autonomy related to how they could best help the person with learning disabilities feel familiar with these transitions.

Respect for autonomy became apparent at three kinds of transitions at the end of life

Challenges to respecting autonomy

- Ascertaining information needs: It was common for relatives and caregivers to be given information about the prognosis rather than the person with a learning disability, raising questions about how to communicate this to the person.

- Communicating about illness and death: Where people had a mild learning disability, this did necessarily lead to more communication and there was a good deal of uncertainty about how to handle difficult subjects along with a fear of upsetting the person.

- Inexperienced in end-of-life care: For all the people with learning disabilities in the study, physical care needs increased which meant that support workers and social workers who were not experienced in end-of-life care faced some difficulties and conflicts between taking over tasks and respecting autonomy and encouraging independence.

- Current and hidden last wishes: Some people had made their last wishes known in end of life plans, but it was important to check that these were still applicable and in the case of people with severe learning disability, wishes were discussed without involving the person because of communication difficulties and because end of life planning had not been carried out when the person was well.

- Magnified dependence: Important decisions for example regarding life-prolonging treatment were often taken in multidisciplinary meetings together with relatives. The authors found no evidence from the interviews that the person with learning was present.

- Conflicting wishes: There were examples where the wishes of the person conflicted with the wishes of others, and people faced real dilemmas between respect for the person’s own wishes and a moral obligation to provide good care.

Important qualities in respecting autonomy

- Attention to information needs: in particular the importance of knowing the person well, understanding their attitude to their illness and towards death had been in the past.

- Connecting – the ability to connect with the person in such a way that they feel able to make of the help that is offered

- Recognising end-of-life care needs: Helping the person feel as comfortable and familiar with the situation as possible

- Giving space to show wishes and preferences: Taking time and being creative in listening to what people have to say, however they say it.

- Discussing dilemmas: Where there was conflict, it was important to name this and discuss the dilemma with the person to find a solution acceptable to all parties.

Conclusion and comment

This study provides a detailed and in depth exploration of the views of professional caregivers and relatives in relation to the dilemmas faced when helping to respect autonomy at the end of life for people with learning disabilities. The qualitative methodology used seems appropriate to help with the understanding of complex issues with respondents. The researchers use case studies to illustrate the issues that are raised by respondents and by interviewing people from a variety of backgrounds, were able to balance differing viewpoints from a number of perspectives.

However, as the authors point out, the interviews were carried out after the event and so respondents were relying on memory. This design also means that it was obviously not possible to include the views of people with disabilities themselves.

The researchers point to three key transitions and report the challenges faced by relatives and caregivers at these points and also reflect on what respondents told them were qualities required to respect autonomy.

They suggest that the key challenge identified by respondents was framed as a need to balance protection with giving more information.

The legal framework in the Netherlands is different to that of the UK. In the Netherlands, there is a model of substitute decision-making for ‘incompetent’ individuals where which representatives (usually a close relative) have the legal power to make substitute decisions, which added additional burdens of stress to close relatives at each of the transitional stages.

Finally, the authors suggest that it may be useful to consider a relational concept of autonomy for end-of-life care for people with learning disabilities, where important aspects are to listen to the story of the person and empathise with their view of the world.

The authors conclude that they found a good deal of potential for respecting autonomy in the analysis of the interviews they carried out, especially if autonomy is viewed as a relational construct. This would require an ‘open, active and reflective attitude’ as well as ‘knowledge on communication and identifying end-of-life care needs’.

It was interesting to note that enabling communication about last wishes was enhanced where there had been ongoing attention to enabling caregivers to jointly discover options for involving people in communication and decision-making. In particular, having had a discussion about end of life planning and having captured some of these last wishes was a good starting point in a number of the case studies described (even if those wishes changed during the transitions, they were a good starting place).

This study may not add a great deal of new information to our understanding of end of life care, but it does provide a richness of insight into how those who are supporting people with learning disabilities at key transitions at the end of their life can be best supported with the potential conflicts and tensions that will almost inevitably arise.

Study provides richness of insight into how to deal with potential conflicts and tensions arising around autonomy at end of life

Links

Bekkema, N., de Veer, A. J. E., Hertogh, C. M. P. M. and Francke, A. L. (2014), Respecting autonomy in the end-of-life care of people with intellectual disabilities: a qualitative multiple-case study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58: 368–380. doi: 10.1111/jir.12023 [abstract]

Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Giatras, N., Butler, G., Cresswell, A., Manners, P. and Bernal, J. (2013), Developing Guidelines for Disclosure or Non-Disclosure of Bad News Around Life-Limiting Illness and Death to People With Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 26: 231–242. doi: 10.1111/jar.12026 [abstract]

Breaking Bad News website

Challenges in respecting autonomy in end-of-life care of people with learning disabilities http://t.co/PAK8QTjR6P