The evidence is clear that a good working environment and satisfying job is great for our mental health: work that enables positive relationships, a sense of achievement, sets goals and gives us chance to grow. It is equally clear that toxic work environments that expose us to psychological hazards on an ongoing basis can be corrosive to our mental health in the short and long term.

Samuel Harvey et al (2017) examined the workplace factors associated with common mental health problems, proposing a new model for assessing these risks in a systematic review and meta-analysis that I blogged for Mental Elf earlier this year.

Mental health at work is a hot topic this year. It’s a welcome focus on a critical issue. Work is a critical setting for most adults of working age. We know that people with mental health problems contribute as much as 12.1% of the UK’s GDP (Mental Health Foundation, 2016).

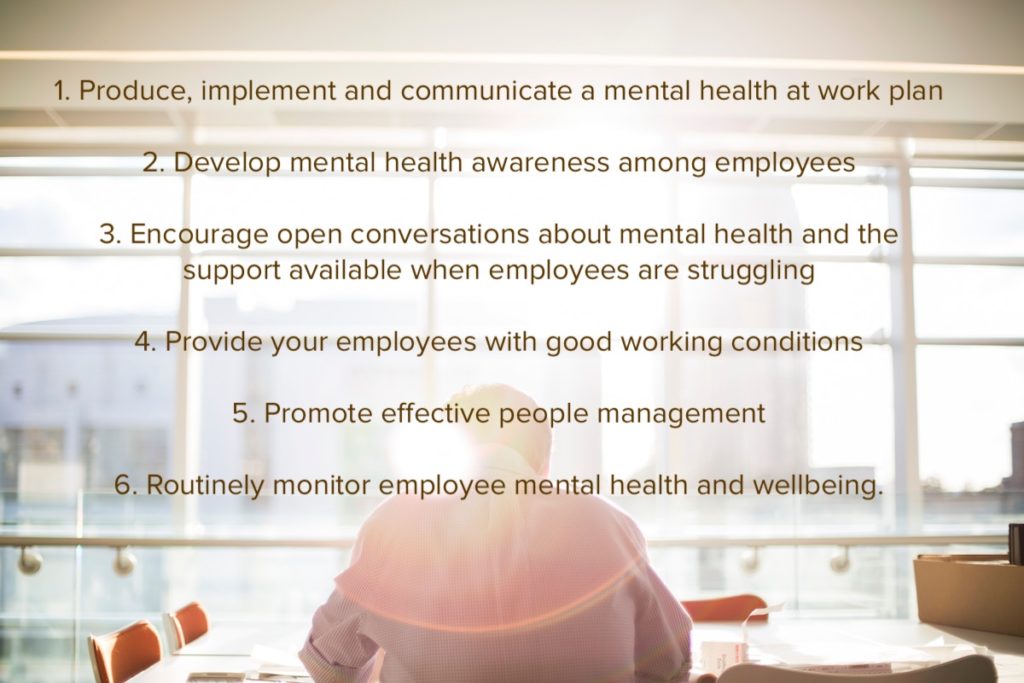

Recently, the UK Government has published ‘Thriving at Work’, an independent review into mental health at work conducted by Paul Farmer of Mind, and Lord Stephenson of Coddenham, a business leader and mental health campaigner (Farmer and Stephenson 2017). The report sets out simple measures that employers can undertake to improve and protect mental health across the workforce, including by supporting those with mental health problems, 300,000 of whom leave the workforce every year. Central to the recommendations are a set of six ‘mental health core standards’ that lay basic foundations for an approach to workplace mental health.

Any mental health at work framework will have at least some focus on the role on managers, and management. On a practical level we also know that the management relationship is key; both in the mediation of everyday tasks like direction, supervision and performance management and in the discussion of any concerns on either side. In the context of mental ill health, it is through management relationships that disclosure of mental distress often occurs, and where the tone is set for support, and reasonable adjustments from an employer.

Line managers frequently report that they are under-prepared to manage mental health. In our research, less than half of survey respondents who had experienced a mental health problem felt well supported by their line manager (Mental Health Foundation, 2016).

There is a huge range of manager training available in the market today. With a growing recognition that training is part of the solution, there is a risk that employers act before training models have been evidenced. It is exciting then to report on the meticulous randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Josie Milligan-Saville and her team. They have managed to devise an extremely robust experimental model that has been delivered in a native workplace context. They retain many elements of control that increase the validity of their findings; that a short, face to face training mental health training course for managers can achieve significant reductions in sickness absence.

There’s a huge range of mental health training for managers available, but few programmes have been robustly evaluated in RCTs.

Methods

This research is a cluster RCT of a 4-hour long face-to-face training programme, with a six month follow up. It was conducted within a large Australian Fire and Rescue service.

Sample and blinding

All managers at duty commander level or equivalent were randomised to receive either a four-hour training intervention called RESPECT training programme, or to be part of a waitlist control group, who were offered the intervention after six months. Duty commanders are second line managers responsible for managing groups of fire stations. They have responsibility for absence management. Though the outcomes of randomisation were not blinded, the staff reporting to the duty commanders were unlikely to be aware of the research.

Intervention and procedure

Managers in the intervention group were offered a four-hour training programme called RESPECT, which combined mental health and communication training. The intervention focused on three areas:

- Key features and impacts of common mental health problems in the workplace

- Roles and responsibilities of senior officers in relation to staff mental health

- Development of effective skills for discussing mental health matters with staff

The third part of the training focused on the RESPECT principles, based on good practice in line management and absence management, which are:

- Regular contact is essential;

- the Earlier the better;

- Supportive and empathetic communication;

- Practical help, not psychotherapy;

- Encourage help-seeking;

- Consider return to work options;

- Tell them the door is always open and arrange next contact.

Managers in the control group were able to access manager support through the employee assistance programme as normal.

Outcomes and analysis

The primary outcome measure was a comparison of sickness absence amongst those supervised by the managers in the study for six months before and six months after the intervention. Anonymised sickness records for these firefighters and station officers was made available to the researchers. Two types of sickness absence: work related (where illness or injury is work related) and standard (where illness or injury is not work related) were assessed.

A secondary outcome measures were the effect on manager knowledge about mental health, prevalence of stigmatising attitudes and confidence with addressing mental health matters with staff. Managers’ knowledge, attitudes and confidence were assessed at baseline, immediately after training and six months after training, using recognised scales.

Rates of work related, and standard sick leave were analysed separately using different models. Appropriate statistical tools were selected for the task. In addition, a cost benefit analysis was performed.

Results

All 128 managers were randomised and given the opportunity to take part. The demographics for those included was broadly consistent across intervention and control groups. Forty-six managers underwent training and 42 were placed on the waiting list. Of these, data for 25 managers in the intervention group were included in the primary analysis of sickness data (1,233 employees) and data for 19 managers from the control group were analysed (733 employees).

In the intervention group, 19 managers completed the six month follow up survey, and in the control group 25 completed it.

Broadly speaking, standard sickness absence increased slightly in both intervention and control groups. This was likely because of the increase in seasonal illness corresponding to the time of the follow up period. Work related sickness absence increased in the control group, but decreased significantly in the intervention group. Additionally, analysis indicated that those in the intervention group were less likely to take standard sick leave, though there was no difference in number of instances for those who did. This may mean that the intervention had a preventive effect on standard sick leave.

After training, managers in the intervention group had significantly higher levels of mental health knowledge and significantly greater levels of understanding of the managers role, and confidence in raising mental health issues. There was no significant change in non-stigmatising attitudes. At six month follow up, the only post-training change to have been maintained was in confidence in dealing with mental health, which remained high, and was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group.

At baseline, 76% of managers in the intervention group had initiated contact the last time they managed someone absent with a mental health problem. At six-month follow up 100% of managers indicated that they had done so, compared with 67% in the control group.

The approximate return on investment for the training was of the order of £9.98 per £1 invested in the programme.

The economic analysis revealed an almost 10-times baseline return on the small investment.

Conclusions

The conclusions are best summarised in the word of the researchers :

In this study, we have shown, for the first time to our knowledge, that a modest investment in mental health training for workplace managers might have measurable benefits. In addition to creating lasting changes in managers’ confidence regarding discussing mental health, manager mental health training had a significant effect on the amount of sickness absence in the two statistical models analysed, although whether the intervention effect is via a reduction in the commencement of standard sick leave, a reduction in overall rates of work-related leave, or a combination of the two remains unclear.

The potential financial benefit for the employer could allow for an economic argument in favour of organisations providing this mental health training for managers, with employees and society hopefully gaining meaningful public mental health benefits.

Strengths and limitations

This is a very well-designed study; a cluster randomised controlled trial, with care taken to minimise bias and ensure only the most appropriate data was analysed. In addition, the choice of an objective primary occupational outcome that could be measured with reliable data makes this amongst the most robust studies that could have been conducted in a natural working environment without a level of experimental control that would risk compromising the authenticity of results.

There were a number of limitations, most flagged by the researchers themselves. First and foremost was the fact that the two analytical models used produced varied effects, which made it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the impact of the intervention on different types of sick leave. The generalised estimating equations model showed a significant reduction in work related sickness absence in the intervention group, whereas the zero-inflated negative binomial model showed a reduction in likelihood of taking standard sick leave in the intervention group, but not in work related sick leave, which casts some doubt on the original finding.

One key consideration is the nature of work in a fire and rescue service. The very circumstances that enable the design to be robust (hierarchical structure, strong data on absence trackable to second line managers, established manager pool) may make the results, and in particular the return on investment, hard to generalise. In addition, the nature of the work means that fire and rescue personnel have a high level of mental health awareness, as dealing with mental health is part of their job roles, and an additional risk in terms of exposure to trauma. This may have had a ‘boosting’ effect on managers preparedness to adopt the course.

More work is needed to confirm the generalisability of these study findings.

Implications for practice

It is clear from this study that it is possible to design manager training that has a sustained effect on manager’s ability to address distress and mental health at work, especially in a context where managers are in possession of good data on sickness absence, and occupationally aware of mental health and health and safety culture. It is interesting to note that the aspects of training that stuck with managers at the six month follow up were in relation to confidence in discussing mental health and awareness of responsibilities. It may indicate that connecting mental health to the everyday role and tasks of management might be more sustainable than addressing mental health awareness or stigma alone; where knowledge and attitudes in this sample did not show sustained improvement at follow-up.

Confidence is key. In our own research just 47% of line managers who had no personal experience of mental ill health felt confident providing day to day line management to a person with a mental health problem (contrasted with 75% of managers who had personal experience) implying that managers with personal experience are a key asset for business (Mental Health Foundation, 2016). Confidence is grown through experience and the opportunity to learn and grow with peers; as such this endorsement of face to face training is welcome.

We are in dire need of better data, and better research on what works in workplace mental health. It is very welcome to see amongst the recommendations in the Farmer/Stephenson review a call both for greater transparency and data availability from employers, and a ten year research strategy on the factors affecting the mental health of the working population (Farmer and Stephenson, 2017).

I am particularly interested in the findings of this study in relation to prevention; whilst the course focused on distress and absence, the intervention group did appear to take less standard sickness absence. This could imply that the intervention helped managers to be more empathic, and more compassionate in their communication, which in turn may lead to earlier discussion of health and social issues that contribute to absence, the early addressing of which may lead to greater personal and organisational resilience. These matters are worthy of further investigation.

Conflicts of interest

Chris O’Sullivan leads the Mental Health Foundation mental health training programme for employers.

Links

Primary paper

Milligan-Saville JS, Tan L, Gayed A, Barnes C, Madan I, Dobson M, Bryant RA, Christensen H, Mykletun A, Harvey SB. (2017) Workplace mental health training for managers and its effect on sick leave in employees: a cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, Available online 12 October 2017 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30405-4

Other references

Harvey SB, Modini M, Joyce S, et al (2017) Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup Environ Med Published Online First: 20 January 2017. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2016-104015 [Abstract]

Mental Health Foundation (2016). Added Value: Mental health as a workplace asset. Mental Health Foundation: London. Available online at https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/addedvalue (accessed November 2017)

Farmer, P and Stephenson, D (2017). Thriving at Work: The Stevenson/Farmer Review of Mental Health and Employers; HM Government; London. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/thriving-at-work-a-review-of-mental-health-and-employers (accessed Nov 2017)

Photo credits

Photo by Climate KIC on Unsplash

Photo by Bethany Legg on Unsplash

Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash

Photo by Nikita Andreev on Unsplash

Photo by Anna Dziubinska on Unsplash

Brilliant work – well done and I can’t belueve that this hasn’t been studied in depth before. One would also presume that managers working in mental health would have the insight and training to be aware of staff mental health, but in my long career haven’t found that to be the case.

[…] the pinch points of modern working life that our preventions strategies should focus on. I’ve also reviewed Sarah Miligan-Savile’s groundbreaking RCT on training effectiveness in an Aus…, which demonstrated the potential of good quality, skills-focused line manager training to make a […]