Mental health, particularly youth mental health, is in crisis. Clinical services are underfunded and overstretched. People who are in marginalised groups, of lower socioeconomic position, and live in more deprived areas generally have worse mental health. They are also more often unable to access healthcare. The COVID-19 pandemic has only increased these inequalities. We need additional and alternative approaches, especially for those who can’t access healthcare. Community-based interventions may provide one way of addressing inequalities in healthcare, reaching more diverse groups than standard clinical interventions.

In the UK, we have over a million community assets, including museums, arts, sports, music, and nature-based activities. Increasing evidence suggests that these assets could be used to support physical and mental health, enhance psychological and social wellbeing, and encourage protective healthcare utilisation (Fancourt & Finn, 2019). Community engagement might support health through a wide range of mechanisms, from psychological, to biological, social, and behavioural. Previous scoping reviews of community engagement and mental health have provided extremely comprehensive overviews of evidence in the field (e.g., Fancourt & Finn, 2019). However, a systematic evaluation of the evidence is needed, as provided in this review (Buechner et al., 2023).

Community interventions may provide one way of addressing inequalities in healthcare by reaching more diverse groups compared to standard clinical interventions.

Methods

This was a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of community interventions for anxiety and depression in adults and young people. Having registered their protocol, the authors performed a comprehensive search across seven databases, followed up on references from included papers, and contacted relevant experts to check no studies had been missed. No restrictions were placed on this search.

The review focussed on a clinically important change in anxiety or depression as the primary outcome, meaning studies either included participants with an anxiety or depressive disorder or aimed to reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms in a wider group. The population of interest was people aged 16 or over. A broad range of community interventions was included, delivered at or by museums, art galleries, libraries, gardens, music or singing groups, youth groups, and sports clubs. They could be delivered online or in person, with or without a keyworker, in groups or individually, and in single or multiple sessions. Any kind of comparison was allowed, including treatment as usual, medication, psychological therapies, or no intervention.

These criteria are broad, meaning many studies were identified (15,534!). As they initially found so many studies, the review was limited to RCTs, which provide gold-standard evidence about the safety and efficacy of interventions. The authors also excluded studies based in care homes or hospital inpatient units, making findings generalisable to people living in the community. They couldn’t quantitatively synthesise studies in a meta-analysis as the studies were too heterogeneous. Qualitative synthesis was used instead.

Results

In total, 31 RCTs were included, with 14 testing community-based exercises (e.g., team sports, dance), 12 community music (e.g., a choir, playing instruments), six community gardens or gardening (e.g., visiting botanical gardens, growing plants), one art gallery visits, one libraries, and one watching baseball. Some tested multiple interventions or combined multiple modalities. No online interventions met the eligibility criteria.

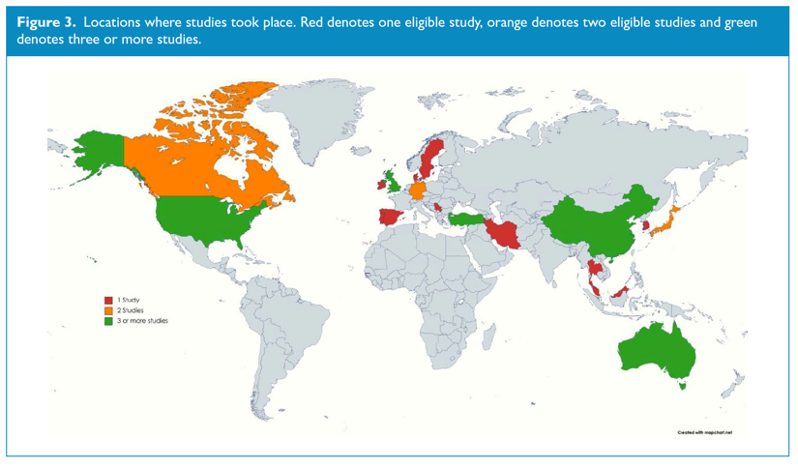

Studies most often focussed on older people (aged 60+), women, or those with an existing illness. Young people were hardly included. Only two RCTs of young people were eligible, with a total of just 98 participants. Most studies were in ‘WEIRD’ (Western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic) societies. Sample sizes were generally very small, with an average of less than 100 (median=59, mean=92).

- Community music interventions were best studied. All but one music RCT reported a decrease in anxiety or depression, although only one reported a clinically significant change in anxiety or depression.

- Similarly, all community exercise RCTs except one reported reduced depressive symptoms, although only two were clinically significant. However, for community exercise, there were rarely significant decreases in anxiety.

- Community gardening interventions that measured anxiety symptoms all reported decreases, and all gardening RCTs reported decreases in depressive symptoms. Only one reported clinically significant changes.

- Other intervention types were tested in single RCTs, all of which found evidence for reduced depression except the art gallery intervention.

The review also aimed to explore mechanisms of action through which community-based interventions might influence anxiety and depression. However, interventions were rarely described in enough detail to understand the potential underlying mechanisms.

Given that community-based interventions are relatively safe (so adverse events are unlikely), study dropouts were used to measure intervention acceptability. Other measures of intervention acceptability were rarely reported. Despite this, community-based interventions seemed to be acceptable to participants, with a mean dropout rate of approximately 10%.

Finally, the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was used to assess bias. Unfortunately, most studies didn’t include enough methodological information to make definitive conclusions about their quality. Where it was possible to assess, the authors found a high risk of bias, mainly because of systematic differences between groups not just due to the intervention.

Research to date focusing on the evaluation of community interventions hardly includes young people as a population of interest.

Conclusions

Community interventions, including sports, music, gardening, art, and culture, were associated with promising but small decreases in anxiety and depression. Very few RCTs found evidence for a clinically significant reduction in anxiety or depression. Firm conclusions cannot be drawn because of the low quality of most studies. Although some interventions had promising efficacy, they weren’t described in enough detail to determine what might be causing reductions in symptoms. Both the activities themselves and the community elements of the interventions are likely candidates.

Community interventions, including sports, music, gardening, art, and culture, were associated with promising but small decreases in anxiety and depression.

Strengths and limitations

This review has many strengths. It provides a strong case for the potential of community interventions. As the first systematic evaluation of the evidence in this field, it was very broad, including a wide range of community interventions in many populations published at any time in any language. The search was replicated, and grey literature was screened. The review was also registered before the formal screening of the search results began, with clear updates made to the protocol. It identifies useful avenues for future research, many of which have a high potential for influencing policy and practice.

This review also has some limitations. There are differences between the registered protocol and the final review, such as additional research questions about what is evaluated in these RCTs, the quality of the data, and a move away from examining the safety of community interventions. The original Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 1) tool was used to assess bias, rather than the updated tool RoB 2 tool. Whilst it’s very difficult to develop an exhaustive search strategy, it’s possible that some RCTs of community interventions were missed. The term “community” was not used in the search, and no specific terms were used to describe community-based activities including social prescribing, heritage sites, parks, running, and cycling. Perhaps coproducing the search strategy could make it more extensive.

Beyond these limitations, this systematic review was greatly limited by the quality of existing RCTs. It was framed as if the authors wanted to focus on youth anxiety and depression, but there clearly wasn’t enough evidence in this population. Even in older adults, most studies were biased. On top of this, there was poor reporting, with inadequate descriptions of interventions and raw data lacking.

Most RCTs of community interventions for anxiety and depression were in older adults in ‘WEIRD’ (Western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic) societies.

Implications for practice

The most obvious implication is that much more research is needed. Although trials of community interventions are feasible, their focus has been too narrow. Community assets have been neglected within experimental research. More high-quality RCTs are needed with larger samples of young people, other populations with high unmet needs, and people in low- and middle-income countries.

This review highlights the potential for community interventions to reach marginalised groups that may not access health services. Despite the lack of robust evidence, the included trials did show promising effects of community interventions on anxiety and depression. So, should we be making changes to policy and practice? I think one of the next priorities should be to consider how we can improve access to community assets and interventions. Outside of writing blogs, my research explores the population-level associations between community engagement and health. One thing we repeatedly find is that there are inequalities in access to community assets, just like with health services (e.g. Bone et al., 2021). People who have higher socioeconomic positions, are not ethnic minorities, and live in wealthier areas are more likely to participate in community activities. This is where social prescribing comes in, a targeted scheme that aims to overcome inequalities by linking individuals to community assets.

Social prescribing can include a massive range of community-based activities, making it really hard to evaluate. There’s basically no evidence for social prescribing in young people yet, and a recent systematic review indicated that it lacks high-quality evidence in adults too (Kiely et al., 2022). But, showing that specific community interventions can support mental health will give us a good indication of whether social prescribing is likely to work. We might have to get creative in the way we evaluate these kinds of interventions, but we still need to consider how to do this robustly whilst accounting for the social gradient in community resources and mental health. This is an exciting area in which there is increasing interest, investment, and evidence – watch this space!

One of the next priorities should be to consider how we can improve access to community assets and interventions.

Further resources for community engagement

- Social Biobehavioural Research Group at UCL

- March Network Legacy

- Culture, Health and Wellbeing Alliance

- Centre for Cultural Value

- National Centre for Creative Health

- National Academy for Social Prescribing

- Arts & Health South West

- Social Prescribing Myth Busters

- Arts Health Early Career Research Network

- Arts, health & wellbeing at KCL

- London Arts and Health

Statement of interests

Jess works in the EpiArts lab, a collaboration between UCL and the University of Florida, funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Pabst Steinmetz Foundation, and the University of Florida. In EpiArts, Jess explores the associations between arts and cultural engagement and health outcomes in US cohort studies. Although she doesn’t develop community interventions herself, Jess’ research is focussed on the potential benefits of everyday community engagement for health. She is also a leader of the Arts and Health Early Careers Researcher Network.

Links

Primary paper

Buechner H, Toparlak SM, Ostinelli EG, et al. (2023) Community interventions for anxiety and depression in adults and young people: A systematic review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry.

Other references

Bone JK, Bu F, Fluharty ME, et al. (2021) Who engages in the arts in the United States? A comparison of several types of engagement using data from The General Social Survey. BMC Public Health, 21, 1349.

Fancourt D & Finn S (2019) Cultural Contexts of Health: The Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being in the WHO European Region. WHO Health Evidence Synthesis Report.

Kiely B, Croke A, O’Shea M, et al. (2022) Effect of social prescribing link workers on health outcomes and costs for adults in primary care and community settings: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 12, e062951.

Photo credits

- Photo by Pauline Loroy on Unsplash

- Photo by sean Kong on Unsplash

- Photo by Quino Al on Unsplash

- Photo by Daniel Funes Fuentes on Unsplash