Disruptive innovation is a cornerstone of the McPin Foundation’s work; they’re a user focused charity geared towards transforming mental health research through co-production, collaboration and dissemination of forward-thinking policy and practice with service users at its heart.

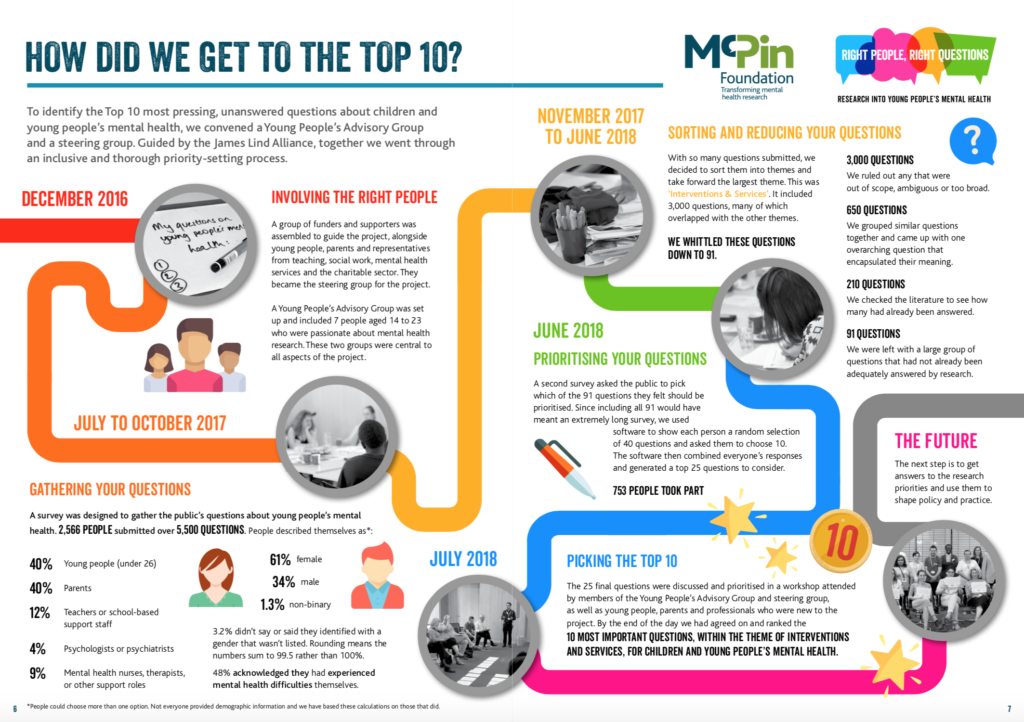

To further these aims, they’ve developed the Right People, Right Questions approach (see the video below), which takes a big picture look at the landscape of mental health research and engages with service users to consider what questions researchers should be asking and answering. This approach was originally developed by the James Lind Alliance and has been used to identify research priorities for lots of health topics over the last few years, and most recently been used to identify research priorities for the field of digital mental health. The methodology has been refined and repeated to come up with a series of research priorities for children and young people’s mental health in a report launched yesterday in parliament. Follow the Twitter discussion at #YoungPeopleMHQ.

Methods

McPin were essentially looking to answer the research question:

What are the top research priorities for children and young people’s mental health, as determined by children and young people, and the people who work with them?

They identify 25 research priorities in their final report which was the result of a two-year process.

An initial survey was carried out identifying the public’s questions about young people’s mental health:

- 5,500 questions were posed by 2,566 people

- 40% of the people asking questions were under 25 years of age

- 48% had experienced mental health problems.

The questions were sorted into themes and the most popular theme (interventions and services) was taken forwards.

The 3,000 questions were then whittled down as follows:

- Removal of questions that were out of scope, ambiguous or too broad

- Grouping similar questions together to create over-arching questions

- Reviewing the literature to remove questions that had already been answered by evidence-based guidelines or systematic reviews.

At this point, 91 questions remained, and a further public survey was carried out to identify the top 25. The final 25 were discussed, developed and prioritised in workshops with a young people’s advisory group and a professionals steering group who were involved throughout the project.

This two year project, with young people and mental health experts at the core, used the established James Lind Alliance methodology to produce a final list of research priorities. Click here to see full sized infographic (PDF).

Results

There are several themes running through the final 25 questions shared in McPin’s report notably:

- The role of schools (Qs 10, 16, 18 and 19)

- Parents (Qs 6, 8, 25)

- The mental health of vulnerable groups (Qs 11,15, 20, 22, 23)

- Prevention and early intervention also appear throughout (e.g. Qs 4, 5, 10, 12, 17, 19)

- Four questions were about specific issues:

- Suicide (Qs 7, 25)

- Stress (Q13)

- Panic (Q24).

Top 25 research priorities for children and young people’s mental health (interventions and services)

The top 25 questions in order of priority were:

- Would the screening of young people be appropriate for the early identification of mental health difficulties, and if so, what would be the best way of carrying this out?

- How can young people be more involved in making decisions about their mental health treatment?

- How can Child and Adolescent Mental Health services (CAMHs), education providers and health and social care departments’ work together in a more effective manner in order to improve the mental health outcomes of children and young people?

- What are the most effective early interventions or early intervention strategies for supporting children and young people to improve mental resilience?

- What interventions are effective in supporting young people on Child and Adolescent Mental Health service (CAMHs) waiting lists, to prevent further deterioration of their mental health?

- What methods can parents use to identify that a child or young person’s mental health is deteriorating?

- Which interventions are effective at supporting suicidal young people?

- How do family relationships, parental attitudes to mental health, and parenting style affect the treatment outcomes of children and young people with mental health problems (both positively and negatively)?

- What are the most effective self-help and self-management resources, approaches or techniques available for children and young people with mental health issues?

- What is the most effective way of training teachers and other staff in schools and colleges to detect early signs of mental health difficulties in children and young people?

- How can the number of effective culturally appropriate approaches available in children and young people’s mental health services be increased, particularly for ethnic minority groups?

- What role does having a healthy lifestyle (e.g. sleep, diet, and exercise) play in the prevention of mental health problems in children and young people?

- What are the most effective interventions for managing and reducing harmful stress in children?

- Do young people who receive a prompt psychiatric diagnosis experience better mental health outcomes than those who wait longer to receive a diagnosis?

- What methods are effective at supporting young men to recognise the signs of mental ill health and access appropriate support? (E.g. stigma reduction)

- At what ages would it be most effective to start to educate children and young people about mental health?

- In what way do children and young people (11-25 years) feel that their mental health condition could have been prevented?

- Which school-based interventions are most effective at promoting and developing emotional wellbeing in children and young people?

- Which school-based interventions are most effective in building mental health resilience in children and young people?

- Are children from low income households waiting longer to access mental health services than children from financially better off households?

- What impact does a longer waiting time for mental health services have on the treatment and mental health outcomes of children and young people with mental health difficulties?

- How can early intervention prevent the development of mental health problems in children and young people with an autistic spectrum disorder or learning difficulty?

- How can homeless young people be supported with their mental health needs?

- Which interventions or methods are effective for young people to cope with panic attacks?

- How can parents identify and support children who are at risk of suicide without increasing the child’s level of distress?

Discussion

The final 25 questions make for interesting reading, especially when bearing in mind that these are 25, as yet, unanswered research questions. When reading through the list, it really brought home to me that child mental health science is still very much in its infancy and we still have so much to learn. It’s an area of increasing investment of research funds and time and McPin’s review of the landscape and indicators for sensible ways forwards is welcome as, allowed to evolve naturally, research can often feel somewhat siloed and piecemeal.

Setting priorities with a strong reference to young people’s wishes is also a welcome focus; though as with all user experience and co-production work; care needs to be taken to utilise user voice whilst also drawing on the experience and guidance of experts to come to an informed and realistic set of recommendations.

Setting priorities with a strong reference to young people’s wishes is a welcome focus.

Strengths

With over 2.5k responses to the initial online survey; the data pool was large, which is commendable. It would, however, be interesting to know more about the demographics of respondents beyond the very basic gender and age information shared, so that we could understand whether the sample was representative of potential service users.

McPin have built on the excellent James Lind Alliance methodology for co-produced priority setting. The Right People Right Questions process developed by McPin is an interesting approach with a particular strength in the open-ended question at the beginning of the process enabling data capture of a very wide range of views. Utilising online surveys to generate volume and reach and face to face meetings to drill down into the detail and set final priorities also seems to have worked well. It is also commendable that the Young People’s Advisory Group were involved in every step of the process, though more details about the recruitment of this group, their demographics and how the process was made truly accessible to and inclusive of them would be welcomed.

McPin’s final report provides a clear focus for researchers and commissioners should they wish to act on these recommendations. As well as giving clear direction for specific areas of research, some of the 25 priorities set the scene for the field more widely; indicating a need to focus on prevention, early intervention and vulnerable groups and to consider culturally appropriate interventions.

During the process of narrowing down the questions posed by the initial survey, 210 unique questions were whittled down to 91 as literature searches indicated that over half of the questions posed had already been answered by existing research (evidence-based guidelines or systematic reviews). This indicates a clear disconnect between research activity and dissemination and raises an important question for the research community about how best to share findings and furthermore, how to empower people to act upon these findings. McPin have committed to sharing the answered questions, but the omission of them from the current report feels like a potentially missed opportunity. Following up on this work feels like an important step.

Knowing the answered questions is perhaps just as important as the unanswered questions. If there’s existing evidence that can have a positive impact on youth mental health, we should be implementing it!

Limitations

McPin chose not to include previously answered questions in their final 25, nor to include questions related to digital technology as these had been assimilated in a parallel piece of work. These omissions mean that whilst the list of research priorities is a potentially useful guide for researchers and commissioners, it may not be truly representative.

There are some surprising omissions in the final list of questions, with no mention of social media or self-harm for example. These are two very often discussed topics when it comes to young people’s mental health, especially in the mainstream media. Whether these questions genuinely didn’t make the list or if they were removed during the pruning process is unclear.

The work is UK-centric which acts as both a strength and a weakness. On the plus side, there are clear directions set for UK researchers and commissioners developed in the context of UK users of UK services. On the other hand it feels important that we also consider the international context given the UK’s reputation for world class research. It would be interesting to consider how these questions sit within the international context and how UK researchers can best be collaborating with, learning from, and informing the international research landscape in order to further the field of child mental health.

A further area for development would be working with researchers, commissioners and policy makers to consider how research time and funding is prioritised in order to ensure that the current work is acted on appropriately rather than filed away to gather dust. It is possible that these priorities may not align with political and research agendas; but if not, we should be asking why not and considering how best to align future research with genuine gaps in the field and the questions that most need answering.

It’s possible that these priorities may not align with political and research agendas; but if not, we should be asking why not.

Next steps

McPin close their report with some aspirational next steps which are worth your consideration. They call on:

- Research funders to provide resources to fund research questions that address these priorities

- Researchers and research institutes to commit to building an evidence base around the priorities, answering specific research questions and including young people in the design, delivery and dissemination phases

- Policymakers to use the answers to these questions to formulate policy that leads to meaningful change

- Young people, their supporters and our project partners to keep the spotlight on these questions and get involved in research projects that take our understanding on these topics forward.

Something for (nearly) everyone to do now!

Conflict of interest

Pooky Knightsmith has no conflict of interest to declare. André Tomlin (Founder of The Mental Elf) was on the Steering Group for the McPin Foundation Right People Right Questions project.

Links

Primary paper

McPin Foundation (2018) Research Priorities for Children and Young People’s Mental Health: Interventions and Services (PDF).

McPin Foundation (2018) Research Priorities for Children and Young People’s Mental Health: Interventions and Services Focus on the Questions (PDF).

Photo credits

- Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

- Photo by Ethan Weil on Unsplash