Anxiety and depression (“internalising disorders”) are among the most common types of psychopathology in young people, and are identified as leading contributors to the burden of disease in this population (Mokdad et al, 2016).

Diagnostic systems like DSM and ICD characterise internalising problems as a set of distinct, disease-like entities. While these diagnostic systems have many benefits (such as assisting clinical decision-making and providing a common language for the field), they also have limitations. For example, the thresholds at which symptoms become “disorder” are arbitrary, there is substantial symptom overlap between disorders, and levels of comorbidity are high.

Some researchers have suggested that the limitations of these diagnostic systems are responsible for the slow pace of new discoveries in psychiatry, and that data-driven approaches that focus on symptoms, rather than diagnoses, could vastly improve our understanding of the nature of psychopathology (e.g. Kotov et al, 2017).

The network perspective is one example of a data-driven approach. It conceptualises psychopathology as a complex network of directly associated symptoms, and allows us to:

- Demonstrate how and where symptoms are related (by exploring the connections between symptoms)

- Identify which symptoms are most important (by exploring what is referred to as “centrality”; highly central symptoms are those of greatest importance, and these strongly influence other symptoms)

- Understand where diagnostic categories are distinct, and where they overlap (by exploring the clustering of symptoms into “communities”).

Previous research has used network analysis to explore psychopathology in adults, and has found a densely connected network of symptoms with strong associations both within and between traditional diagnostic constructs, which suggests that the boundaries of diagnoses are not well-defined (Boschloo et al, 2015).

This recent open access study by Eoin McElroy and Praveetha Patalay used network analysis to investigate the distinctiveness of diagnostic boundaries for internalising disorders in children and adolescents (McElroy & Patalay, 2019).

Internalising disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety, OCD) are frequently comorbid, raising questions about the boundaries between these diagnostic categories.

Methods

Sample

The study used routinely collected data from 81 Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services in England between 2011 and 2015. In total, data from 37,162 children and adolescents aged 8 to 18 years (63% female) were included.

Measures

Internalising symptoms were measured with the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS), which is a 47-item self-report measure. Items can be summed to form DSM-based sub-scales corresponding to:

- Separation anxiety,

- Social phobia,

- Generalised anxiety,

- Panic,

- OCD (Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder) and

- Major depression.

Analysis

Head’s up: network analysis is a bit complicated. Stats nerds might like to read McNally (2016) to learn more about the methods underlying this approach, but here’s a brief summary of what the authors did:

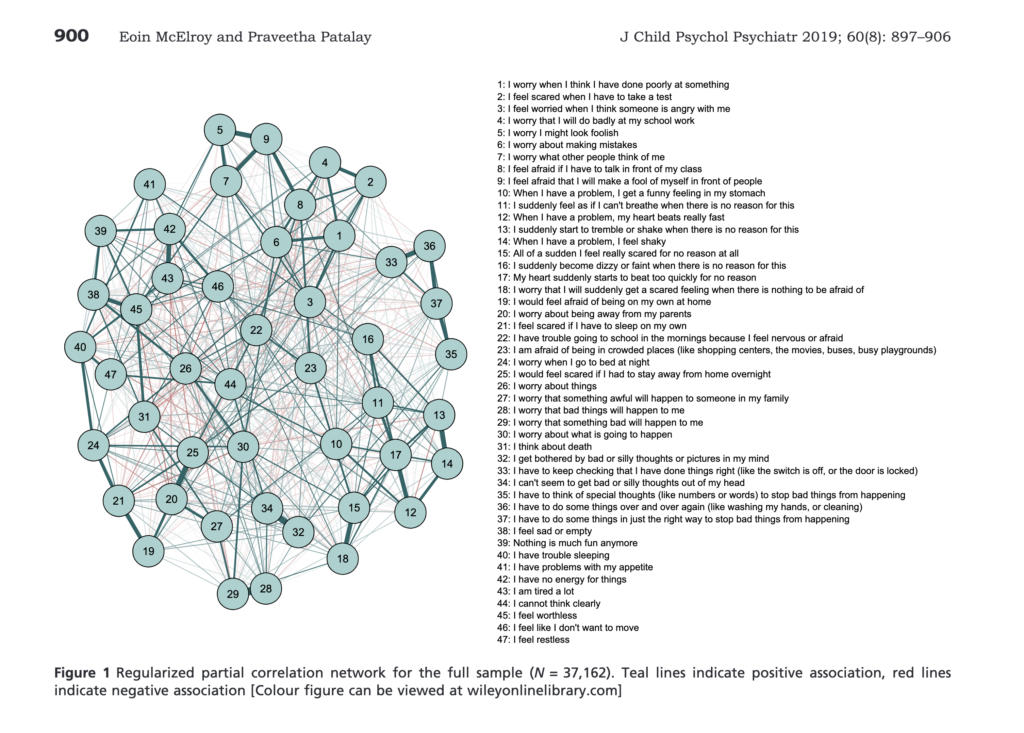

Network analysis was performed by calculating correlations for the 47 symptom variables, then using these to estimate a partial correlation network using the R package ‘qgraph’. The clustering of symptoms was explored using the walk-trap community detection algorithm in R. The authors also explored sex and age differences by splitting the sample into subgroups (girls and boys; 8-11, 12-14, and 15-18 years).

Results

Overall network structure

Overall, there was a “multitude of predominantly weak connections between symptoms”. The most central (i.e. the most important/influential) symptoms across the whole sample were those related to panic, fear of making a fool of oneself in public, worry and worthlessness.

Diagnostic boundaries

There was little clustering of symptoms into “communities” (i.e. diagnoses). The network with the best fit identified six communities, but the overall strength of connection was low, and there were widespread cross-community connections, indicating substantial overlap between symptoms in different communities.

Sex- and age-related differences

The overall structure and clustering of the network was similar for girls and boys, and for children of different ages. This suggests that internalising problems are no more or less defined for these different groups. However the connectivity of the networks were greater for older children, which suggests that as children develop, the associations between symptoms increase. The authors suggest this could be because internalising symptoms reinforce each other over time.

There were also differences in the centrality of symptoms across the age groups. Restlessness and fatigue were the most central symptoms in the oldest age groups, while fears (e.g. going to bed, doing badly at school) were most central for the youngest group. Since highly central symptoms strongly influence other symptoms, these could be key targets for intervention.

Internalising symptoms formed a highly interconnected network structure, with little distinct clustering of symptoms that pertained to DSM diagnostic criteria. (View full sized image).

Conclusions

- Internalising problems in children and adolescents are characterised by lots of weak connections between different symptoms, with little clustering of symptoms into “communities” and a lack of clear diagnostic boundaries.

- This challenges the idea of internalising problems as a set of distinct disorders.

The highly interconnected network structure presented in this research challenges the idea that internalising disorders are discrete diagnostic entities.

Strengths and limitations

- This was the first study to use network analysis to explore the nature of internalising symptoms in children and adolescents

- It benefitted from a large clinical sample that spanned a wide age-range (8 to 18 years)

- The large sample was a particular strength because (as the authors say themselves) many of the previous studies in this field may have been underpowered due to small samples (see McElroy & Patalay, 2019)

- Separating the sample into sex and age sub-groups was a strength, and helped to identify differences in the nature of internalising symptoms for these groups

- The study used an algorithm to identify clusters of symptoms, which is a strength over previous research that has mostly relied on visual inspections of network graphs to identify clustering

- The RCADS, which was used to measure internalising symptoms, is shaped by DSM criteria, and this is not necessarily reflective of the entire spectrum of internalising problems

- The RCADS also doesn’t include sub-scales for some DSM disorders, such as agoraphobia or specific phobias.

Given that stronger connectivity between symptoms was found for older children, it is possible that internalising symptoms reinforce each other over time.

Implications for practice

Given that stronger connectivity between symptoms was found for older children, it is possible that internalising symptoms reinforce each other over time. Other research has shown that those with more strongly connected symptom networks are less responsive to treatment, so this highlights the importance of early intervention. The findings also emphasise the need for clinicians to focus on individual symptoms rather than diagnoses, as argued in this previous Mental Elf blog by Warren Mansell.

There are bigger questions that arise from studies like this though, such as, what is the value of diagnostic systems for mental health problems, and should we abandon them altogether? These are by no means new concerns; there has been widespread debate about the nature of psychopathology and the value of diagnostic systems for some time (for a discussion see Clark et al. (2017) or Kotov et al. (2017)).

As the authors highlight:

The lack of distinct clustering corresponding to our most widely used diagnostic criteria and the high degree of cross-community associations observed in the present study lend greater support to recent calls for more empirically based conceptualisations of mental illnesses that move away from distinct disorder entities.

Classification systems that take a dimensional approach to mental illness, such as the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) or Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), provide feasible alternatives to the way that we research, treat, and make sense of mental health problems. Some researchers argue that by adopting these dimensional approaches, we can make greater and faster progress in areas as diverse as identifying biomarkers for mental health problems, establishing genetic and environmental risk factors, and improving the efficacy of treatments (Kotov et al, 2017; McNally, 2016).

But systems like DSM and ICD are deeply embedded within clinical practice and government policy, and some argue that they are helpful, if not essential, to effective clinical decision-making. As yet, there is little consensus about how best to conceptualise mental illness. What is clear from this study, however, is that internalising problems in children and adolescents are characterised by a number of highly inter-related symptoms, with little evidence that these symptoms cluster into distinct disorders.

The findings lend support to recent calls for more empirically based conceptualisations of mental illnesses that move away from distinct disorders.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

McElroy E & Patalay P. (2019). In search of disorders: Internalizing symptom networks in a large clinical sample. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(8), 897-906.

Other references

Boschloo L, van Borkulo CD, Rhemtulla M, Keyes KM, Borsboom D & Schoevers RA (2015). The network structure of symptoms of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. PLoS One, 10(9), e0137621.

Clark LA, Cuthbert B, Lewis-Fernandez R, Narrow WE & Reed GM (2017). Three approaches to understanding and classifying mental disorder: ICD-11, DSM-5, and the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 18(2), 72-145.

Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, Brown TA, Carpenter WT, Caspi A, Clark LA, et al., (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies (PDF). Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), p454-477.

Mansell W. (2018) The transdiagnostic approach to anxiety: The case is made (again!) #TransDX2018. The Mental Elf, 17 Sep 2018.

McNally RJ (2016) Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 86, 95-104. [PubMed abstract]

Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, Mokdad AA, Bcheraoui CE, Moradi-Lakeh M, Kyu HH, Barber RM, Wagner J, Cercy K, et al. (2016). Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people’s health during 1990-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet, 387, 2383-2401.

Photo credits

- Photo by Luke Pennystan on Unsplash