Conduct disorder (CD) is the most common type of mental health disorder seen in young adolescents. It is prevalent in around 5% of young people and is distinguished by repetitive patterns of anti-social, aggressive or defiant behaviour (NICE, 2017).

Current interventions comprise of in-clinic family-based models of therapy. This practice considers family dysfunction and maladaptive parenting style to be the main drivers of conduct disorder in children (Johnson, 2001). However, regular attendance at therapy by both the family and child is important for positive outcomes to be met (Gopalan, 2010).

Engaging these families in therapy is a hurdle for service providers; with 22% of families failing to complete initial assessments and 60% of families terminating treatment early (Thompson, 2009). Reasons for this include unreliable public transportation (we’ve all been there), variable work schedules and lack of financial resources (Kazdin, 1999).

So, if patients not coming into the clinic is the main factor behind poorer outcomes, then what if the clinic could come to the patient instead?

A CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health) therapist conducted a small-scale study observing clients’ and therapists’ perspectives on the effectiveness of Home-Based Treatment (HBT) for children with Conduct Disorder (Morino, 2019).

Engaging families in therapy for conduct disorder can be challenging.

Methods

The study used a qualitative approach to look at families and therapists’ perspectives on the treatment they had been receiving for six months.

The treatment was an assertive outreach model utilising various schools of family therapy and skills training, delivered at the client’s home.

Participants consisted of:

- Four participating families: 3 white, 1 black: 2 males, 2 females (ages 10-14)

- Children with diagnosis of conduct disorder (with or without ADHD)

- Three therapists: R-team (Reframe Team)

The data was collected from:

- Focus groups with therapists

- Interviews with client families

- Audiotaped therapy sessions

The study utilised self-reflexivity (“awareness of difference”) to look at children and family ideas of positive change.

The data were analysed using grounded theory to compare the therapist’s perceptions, family’s perceptions and therapy practice.

Results

The main themes from the analysis were:

Accessibility

- Physical accessibility: Both families and the team agreed that Home-Based Treatment (HBT) improved physical access, leading to fewer missed appointments and ensuring greater availability of the therapist when needed

- Accessible language: Families appreciated accessible (“down to earth”) communication styles and said it led to greater engagement in the treatment by the children

- Overall, they found that accessibility led to a good therapeutic relationship with the families feeling acknowledged, which affected the change process positively.

Power and agency

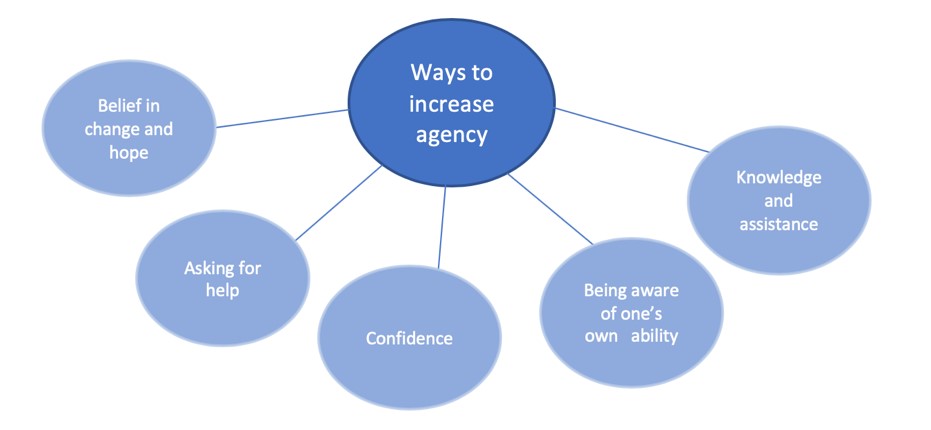

- All families oscillated between the two states of power and agency; agency led to feelings of confidence and control over child situation, whereas powerlessness led to attributing the change process to be only within the child’s control. The image below indicates the main ways of improving agency as discussed in the paper.

Therapy structure and home-based treatment as a tool to increase agency

- The families agreed that feelings of agency were increased when therapists utilised a flat, non-hierarchical structure in which the therapist “positioned themselves alongside the family” and adopted a “permission seeking practice.”

- It was found that the act of allowing the therapist into the home by the family led to a repositioning of the power dynamic. The therapist was now perceived a “helper not rescuer” working as a team with the family to better the child’s health.

Perspectives of change

- The client’s perspective: Overall, a positive change in behaviour was found. It was found that treating the children calmly instead of “nagging” helped spur the change process. It allowed children to have more time to reflect on their actions, listen to their parents and calm down. Families felt more hopeful about their child’s progress and felt included in the process of change.

- The therapist’s perspective: The therapists saw value in HBT and found that it led to a more personalised approach to therapy. They said that it allowed them to incorporate the home into a personalised therapy experience and draw rich information from day-to-day family activities (e.g. visits from neighbours). They also found that it helped them redefine their own ideas surrounding aspects like hierarchy, power and boundaries within the therapeutic context.

This small qualitative study suggests that agency can lead to feelings of confidence and control for children with conduct disorder and their families.

Conclusions

- The authors of this small qualitative study concluded that Home-Based Treatment (HBT) was beneficial in treating conduct disorder in “hard to reach” families as opposed to in-clinic treatment

- They found that this led to greater access to resources and fewer missed appointments

- HBT also strengthened the therapeutic alliance and turned treatment into a collaborative experience, allowing the family to take charge and feel in control of the outcome

- Therapists also found it a useful exercise in expanding their knowledge and their professional skills indicating its widespread potential in treating conduct disorders.

The study emphasises teamwork in bringing about positive changes in the child with conduct disorder.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

- The study used several perspectives, including the therapist, the family and the child. This triangulation is useful in providing a holistic understanding of the treatment.

- The paper highlighted the benefits of Home-Based Treatment (HBT) for children with Conduct Disorder (CD), especially with regards to adherence to appointments and greater engagement in treatment: an issue that is notorious when treating CD in the clinic.

- The study looked at the role of the family home, family dysfunctions and parenting practices in CD. The study also emphasises teamwork in bringing about positive change in the child. This is a more collaborative approach than pharmacological methods, which require only the child to change and not their environment.

Limitations

- The study was time constrained leading to only a small group of families involved. Therefore, it is hard to gauge whether the successful experiences of a few families can be generalised to claim the overall success of family therapy. Additionally, it is difficult to tell if all therapists will be open to this approach due to the duration of the study and it is unclear how this may affect professional boundaries in long-term therapy.

- The paper looks at CD in children with present families and homes that are willing to partake in therapy. Whereas, the most severe forms of CD are prevalent in children in foster care or those with abusive or negligent families (Jaffee, 2003). Therefore, HBT cannot be used in children with CD with absent families or families unwilling to partake in treatment/allow a therapist into their home.

- Using “self-reflexivity” to assess change isn’t reliable. Research indicates that parents face difficulties in assessing their child’s behaviour (i.e. may look for positives/ may downplay negatives) (AAP, 1999). Also, only one child actually spoke about changes in the study. As the rest of the children’s input on the change process wasn’t actually available, it is hard to gauge the effectiveness of this treatment.

Further work is needed to explore how home based treatment could be adapted for looked after children.

Implications for practice

The paper provides useful insights for therapists on tackling issues of engagement and retention in treatment. The therapists in the study found HBT a useful and easy approach to adapt to, indicating the potential for wide-spread application. This can also be applied to treatment of other disorders like depression, which are characterised by feelings of hopelessness and struggles to leave the house. More research into training methods for therapists should be initiated to improve factors like setting boundaries and ensuring therapist comfort within home settings (Glebova,2011).

The study also emphasises how HBT can improve collaboration in therapy and de-centralize the role of the therapist. I find this a useful practice to encourage in all forms of therapy as it increases confidence and hope in the client’s ability to facilitate change. My experiences as an Art Therapist for victims of sexual abuse in Sri Lanka emphasised the importance of building feelings of self-efficacy and hope in vulnerable patients.

I found the paper unclear about how implementation might work, such as the additional costs to the NHS by providing HBT on a larger scale. An analysis of the mental-health budget indicates that funding for treatment is currently insufficient with future demands expected to rise (Health Foundation, 2018). I think a follow-up feasibility study should be undertaken looking at whether the implementation costs are compensated by the reduction in patient no-show costs from HBT.

What might it cost the NHS to provide home-based treatment on a larger scale?

King’s MSc in Mental Health Studies

This blog has been written by a student on the Mental Health Studies MSc at King’s College London. A full list of blogs by King’s MSc students from can be found here, and you can follow the Mental Health Studies MSc team on Twitter.

We regularly publish blogs written by individual students or groups of students studying at universities that subscribe to the National Elf Service. Contact us if you’d like to find out more about how this could work for your university.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper:

Morino Y (2018). Ideas of the change process: family and therapist perspectives on systemic psychotherapy for children with conduct disorder. Journal of Family Therapy. 2018;41(1):29-53.

Other references:

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), (1999). Caring for Your School-Age Child: Ages 5 to 12 ISBN 0-553-37992-5

Glebova T, Foster S, Cunningham P, Brennan P, Whitmore E. Examining therapist comfort in delivering family therapy in home and community settings: Development and evaluation of the Therapist Comfort Scale. 2012;49(1):52-61.

Health Foundation (2018). Response to the Autumn Budget 2018 Day to day spending on the wider health budget will fall by £1bn in real terms next year. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/news/response-to-the-autumn-budget-2018

Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A (2003). Life with (or without) father: the benefits of living with two biological parents depend on the father’s antisocial behavior. Child Development. 2003;74:109–26 [Abstract]

Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Smailes E, Brook JS (2001) Association of Maladaptive Parental Behavior With Psychiatric Disorder Among Parents and Their Offspring. Arch Gen Psychiatry;58(5):453–460. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.453

Kazdin A, Wassell G (1999). Barriers to Treatment Participation and Therapeutic Change Among Children Referred for Conduct Disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28(2):160-172. [Abstract]

NICE (2017). Conduct disorders and antisocial behaviour in children and young people: recognition, intervention and management. Available from:https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg158/documents/conduct-disorders-in-children-and-young-people-final-scope2

Slesnick N, Prestopnik J (2004). Office versus Home-Based Family Therapy for Runaway, Alcohol Abusing Adolescents. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2004;22(2):3-19.

Thompson S, Bender K, Windsor L, Flynn P (2009). Research Note Keeping Families Engaged: The Effects of Home-Based Family Therapy Enhanced with Experiential Activities. Social Work Research. 2009;33(2):121-126.

Photo credits:

- Photo by Lea Böhm on Unsplash

- Photo by Alexander Dummer on Unsplash

- Photo by author

- Photo by Hannah Busing on Unsplash

- Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

- Photo by Josh Appel on Unsplash