Many of us hear voices that no-one else can hear. The experience of hearing voices is unique and different for every individual. As the Understanding Voices website tells us, for some “the voices can be comforting, kind and encouraging; for others, the voices are intimidating, critical and abusive” (Understanding Voices, 2018).

There is a lack of user-focused research on children and young people (CYP) who hear voices. Most of what is known comes from adult studies. Exact figures on lifetime prevalence are hard to find, but recent Dutch research suggests that figures are similar in children (12.7%) and adolescents (12.4%), but these two groups differ significantly from the adults (5.8%) and the elderly (4.5%) (Maijer et al, 2018).

So the experience of hearing voices is about as common for young people as having asthma, but of course it is not viewed by many people in society as a ‘normal experience’.

A new study by Sarah Parry and Filippo Varese aims to provide important insights into the experiences of voice hearing in young people (Parry and Varese, 2020). This #CAMHScampfire blog summarises the new research and if you read through to the end you’ll hear about a free online discussion of this topic taking place on Thursday 28th January 2021.

Voice-hearing is common in children and adolescents, with more than one in 10 having these experiences.

Methods

This was a qualitative study in which participants were recruited via social media, health trusts and support groups. CYP aged 13-18 were asked to opt-in to the study if they identified as hearing voices that others could not. They did not have to have a clinical diagnosis or be connected to a mental health service. The study was available in the English language.

Because of previous difficulties in accessing the experiences of CYP who hear voices, the researchers developed a specific platform for research engagement that protected their confidentiality. This incorporated the researchers’ own 18-item self-report questionnaire (the Manchester Voices Inventory for Children or MAVIC), plus 17 qualitative questions, which are included in the published paper’s appendices.

The researchers involved CYP with lived experience of hearing voices in the development of the online platform and also in evaluating the data.

Data analysis

The analytic method incorporated narrative and phenomenological analyses of the data from answering these questions. A narrative approach interprets qualitative data as stories that participants tell to make sense of their world. The phenomenological approach supplements this by considering how people make sense of their subjective experiences.

Data analysis included discussions of the findings with experts-by-experience and service providers to explore aspects of the data from a range of perspectives.

Results

52 complete data sets were obtained across all the questions. The average age of onset of voices was 9.45 years. Half of participants had not sought healthcare or community-based support; 36% had and 14% ‘preferred not to say’.

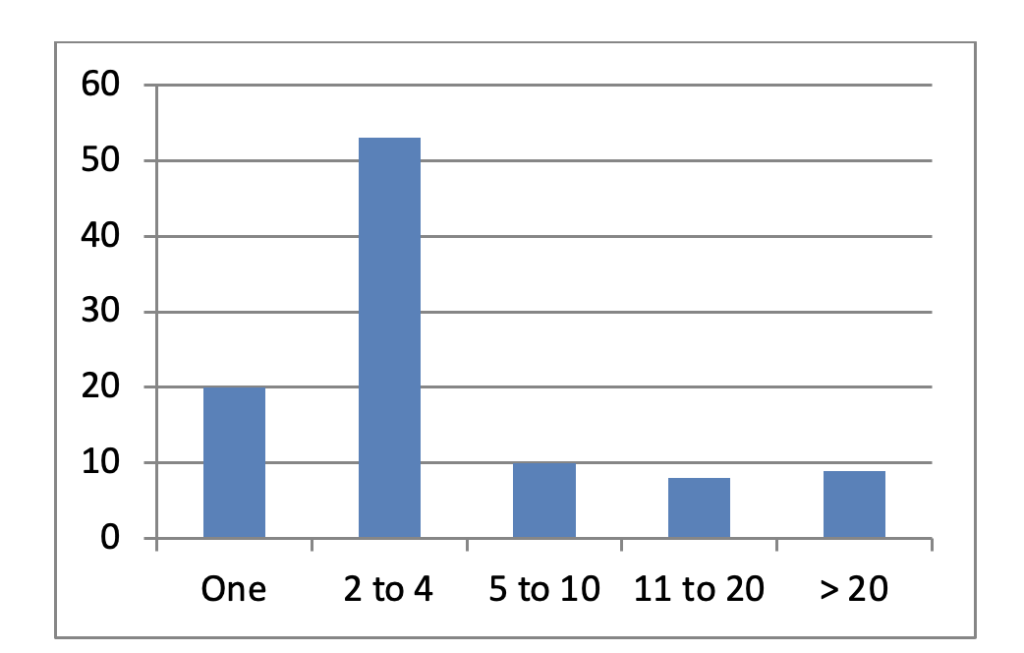

Percentage of participants reporting one, 2 to 4, 5 to 10, 11 to 20 or 20 or more voices.

Participants reported negative (56%), positive (23%) and mixed (21%) emotions in respect of their hearing voices. However, overall, participants reported voices caused greater negative than positive effect. The majority of participants felt that the voices were difficult to ignore.

There were important differences between positive and negative voices in terms of form and function. Here we present a brief comparison but we do refer the reader to the published paper for a fuller picture.

Pleasant and agreeable voices |

Threatening and critical voices |

| Form

Trustworthy, reliable, safe, characterised with personal qualities, described with pronouns (often gender neutral or female), with agency, kind. |

Form

Commanding, ghost-like, haunting, fast speaking, controlling, antagonistic. |

| Function

Advice, support, safety, companionship, listening, social connection, creative inspiration, decision-making, reassurance, motivation, helpful. |

Function

Anxiety provoking, interfere with concentration, disturb sleep, represent past people and/or experiences, nurture self-doubt. |

Participants understood positive experiences of voices as combating loneliness, helping deal with difficult situations, providing comfort and compensating for loss.

They seemed to find it more difficult to describe the presence or purpose of distressing voices, making the process of understanding them more complex.

More than half of participants reported a negative impact from their voices, causing anxiety, disturbed sleep and unwanted distraction. They also found these kinds of voices difficult to control and make sense of.

Strengths and limitations

Broadly, it seems that this is a valuable piece of research that provides useful, authentic insights.

It was good that they involved experts-by-experience in the research process throughout, including data analysis.

There doesn’t seem to have been validation of the MAVIC instrument, or piloting and revision of the research platform. This might affect the validity of the data and could also have affected the sample recruited and data gathered. Only 52 of the original 68 (76%) completed the full survey. The reasons for this are not explored.

It was English language only; around three quarters were from US or UK, with a handful from five other countries.

I had never heard of Foucauldian-informed Narrative Analysis (FNA) so I did a bit of digging around it. Narrative analysis is where you interpret qualitative data as stories that make sense of the world. Foucauld was into knowledge and power structures and relationships. In this study, we have a population for whom stigma, including self-stigma, substantially mediates how they think of their experiences and relate them to others. It is therefore appropriate to deploy an analytical framework that directly addresses these power imbalances.

Furthermore, they married this analysis up with a phenomenological approach, which looks at how people make sense of their subjective experiences. This seems to cover all the bases!

For many young people, voice hearing is a normal part of growing up and not something that will necessarily lead to a more serious clinical diagnosis like psychosis.

Conclusion

The two most striking take-homes are:

- The study shows that hearing voices has an impact beyond those with a clinical diagnosis

- Hearing voices can have positive impacts as well as negative (but for more than half of participants, it was the latter).

We might therefore expect that stigma-reduction measures could reduce voice-related distress. Another approach would be to help young people develop the skills to contextualise the voices they hear, and understand their origin.

Although, as noted in the study, this would be easier to achieve with positive voices than negative ones, which were harder to control. There may be feedback loops at work in the interaction of mental distress and hearing the negative voices. It seems that here is the most urgent need for further research work.

The research platform itself shows promise as a way of engaging with participants who may not want to contribute face-to-face for whatever reason. Indeed, the participants themselves said as much:

This survey helped me get my feelings out.

Thank you for giving me a place to talk openly about my experiences!

What should we do as a society to ensure that young people who hear voices are not stigmatised and excluded because of these normal experiences?

#CAMHScampfire

Join us around the campfire to discuss this paper

The elves are organising an online journal club to discuss this paper with first author Dr. Sarah Parry, an independent expert, a young person and our good friends at ACAMH (the Association of Child and Adolescent Mental Health). We will discuss the research and its implications. The webinar will be facilitated by André Tomlin (@Mental_Elf).

The focus will be on critical appraisal of the research and implications for practice. Primarily targeted at CAMHS practitioners, and researchers, ‘CAMHS around the Campfire’ will be publicly accessible, free to attend, and relevant to a wider audience.

It’s taking place at 5-6pm GMT on Thursday 28th January and you can sign up for free on the ACAMH website or follow the conversation at #CAMHScampfire. See you there!

Conflict of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

Parry S, Varese F. (2020) Whispers, echoes, friends and fears: forms and functions of voice-hearing in adolescence. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Volume 2020, doi:10.1111/camh.12403

Other references

Maijer, K., Begemann, M., Palmen, S., Leucht, S., & Sommer, I. (2018). Auditory hallucinations across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 48(6), 879-888. doi:10.1017/S0033291717002367