Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) refers to research that is carried out in collaboration with members of the general public, and is an approach increasingly used in mental health research (check out Nia Coupe’s Mental Elf blog to learn more about PPI and co-production). Young people’s involvement is particularly important given the right for children’s input to be heard in matters which affect them (Fløtten et al., 2021; UN General Assembly, 1989). There are also many benefits for research when young people are involved, such as:

- Improved recruitment

- More robust study design

- Better translation of research into practice

- Increased acceptability and impact

However, when considering the involvement of young people in mental health research, the focus is often on legal rights or the potential benefits for the researchers – not the benefits to young people. This issue was noted by Watson et al. (2023), who sought to explore young people’s experiences of being involved in research in order to understand how young people feel they benefit best, and how researchers can facilitate this.

When involving young people in mental health research, the focus is often on how they can help the research process and not how they themselves might benefit; this is what Watson and colleagues (2023) aimed to explore.

Methods

13 semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants about their experiences of taking part in mental health research when they were aged 11-16 years old. These interviews were led by co-researchers (young people with lived experience of mental health problems and involvement in research), who were trained and assisted during the interviews by a researcher experienced in qualitative research.

Transcripts from the interviews were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Braun & Clarke, 2019). This was a collaborative process, with the co-researchers specifically aiding in finalising themes.

Authors followed the COREQ checklist for qualitative data and guidelines for qualitative research (Harper & Thompson, 2011; Tong et al., 2007).

Results

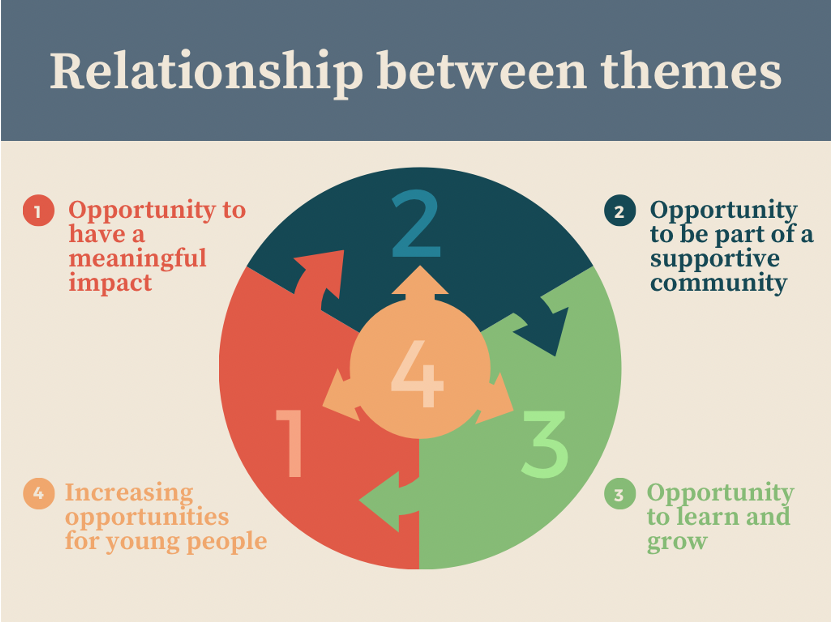

Analysis generated 4 key themes, with associated subthemes:

Theme 1: Opportunity to have meaningful impact

- An important incentive was the chance for young people to use their experiences to help others, which was experienced as rewarding.

- Young people described a sense of pride and empowerment when seeing their contributions being used meaningfully in the community.

- Participants highlighted the importance for young people in getting to see the impact of their contribution, and emphasised regular contact from researchers during and after involvement to keep young people updated.

Theme 2: Opportunity to be part of a supportive community

- The opportunity to build relationships with peers was important to the young people interviewed. Participants felt that they could be more open in discussions when they had formed friendships with people with similar experiences, and so believed that researchers should build in time for non-research interactions between participants. However, it was acknowledged that online-only research could hinder relationship formation.

- Participants discussed the role of researchers in creating a supportive community for the young people involved, and the need for them to be “normal people” rather than “professors in white lab coats” to cultivate this safe space.

- Balance was needed between not forcing young people to share their experiences, but also not judging them for what they did discuss. Participants also suggested that researchers should be sensitive to potentially triggering topics and regularly check in on participants.

Theme 3: Opportunity to learn and grow

- The first and fifth subthemes highlighted how aspects of young people’s involvement could help them in the future, like inspiring them to pursue a career in psychology and developing transferable skills like leadership and teamwork.

- The third and fourth subthemes showed how young people’s involvement could develop their character, by understanding more about themselves and relating to others, as well as having more confidence in their opinions.

- The second subtheme identified the key role of the researcher in this, by helping young people understand the skills they have learned so they can use them in other situations (e.g., writing personal statements).

Theme 4: Increasing opportunities for young people

- Participants highlighted how hard it was for young people to know they can be involved in research, with many describing an inner circle of involvement and it being difficult to find opportunities without this knowledge.

- Emphasis was put on researchers showing respect for young people’s commitments, and the importance of flexibility. Features such as working online and having support from school and parents were also described as aiding involvement.

- Finally, participants discussed the importance of advertising opportunities on social media and in schools, where they will more easily reach young people, as well as making an effort to reach underrepresented groups who may not be involved otherwise.

Figure 1. Adapted from Figure 5 in Watson et al. (2023), made on Canva by Melanie Luximon.

Themes 1-3 highlight the opportunities available to young people when they are involved in mental health research, whereas theme 4 describes how these opportunities can be made available to all young people, especially those typically underrepresented in research.

Conclusions

Watson et al. (2023) conclude their paper by placing a spotlight on the active role of the researchers in facilitating these benefits to young people, through four suggestions for practice:

- Researchers showing young people the impact of their work to help facilitate a sense of empowerment and pride.

- Researchers creating safe communities so that young people feel comfortable. This includes being friendly, supporting young people with their mental health, and allowing young people to have non-research interactions to bond with each other.

- Ensuring that funding applications include a budget for supporting young people’s involvement in research.

- Utilising ‘creative’ methods to advertise opportunities to under-represented groups, as well as advertising more specifically to young people on social media and in schools.

Watson et al. (2023) highlight four key suggestions for practice, including collaborating with schools to advertise research opportunities to young people.

Strengths and limitations

These findings are supported by several previous studies, which is a major strength of this research. For example, Fløtten et al.’s (2021) review of studies involving young patients as co-researchers echoed the third theme identified in the present research, as they found that involvement in research can empower young people and build their skills.

The study is methodologically robust, clearly following the COREQ checklist and demonstrating transparency in the availability of the interview topic guide and initial codes. By utilising reflexive thematic analysis in the research, the co-researchers were able to use their own subjective experiences when interpreting themes from the data (Braun & Clarke, 2019). This was an appropriate method for this study, as the co-researchers were also young people with similar experiences to the participants, and so their contributions may increase the accuracy and impact of the analyses.

However, the paper is also somewhat limited in reflexivity, as the authors do not consider the strengths or limitations of the study. Watson et al. (2023) identifies the involvement of co-researchers as a strength, yet there is no evaluation of the methodology or discussion of contradictory results. For example, it is described that young people reported online research can restrict their ability to form bonds with other participants, which is key to improving their involvement . However, it is also pointed out that working online is important for flexibility. This is quite contradictory, and the research could have been improved by discussing this.

Co-researchers in this study used their own lived experiences when analysing the data for themes in a reflexive thematic analysis, potentially increasing the accuracy of their identified themes.

Implications for practice

The authors provide some useful suggestions for researchers to consider when including young people in mental health research.

Opportunities need to be widely advertised to any young person who may be interested. Transferable skills are an important commodity for young people who are entering the workforce for the first time or applying to university. ‘Experience required’ is a dreaded bullet point for many young people, including myself (Melanie), on applications and involvement in research is a fantastic opportunity to develop skills which may seem like second nature to more experienced workers, such as writing emails.

Watson et al. (2023) point to social media and schools as being viable avenues for promoting opportunities for research involvement. Regarding social media, demographics of certain sites should be considered when researchers are deciding which platform to use to promote their opportunities. Twitter, for example, is often used to advertise research to young people, but 13-17 year olds only make up 6.6% of Twitter users, and the demographic most reached by Twitter are those aged 25-34 (Dixon, 2022). In contrast, those aged 13-24 made up 38.8% of Instagram users, and the 15-25 age group is by far the greatest user demographic of TikTok (Ceci, 2022; Dixon, 2023). In light of this, researchers should consider using less traditional platforms when advertising to a younger demographic – although this can be intimidating (as Nina found out when trying to wrangle TikTok). It seems like there is also an opportunity here for research funders to provide up-to-date social media training for researchers – dare we say with the involvement and expertise of young people?

Watson et al. (2023) also make the argument that researchers should include funding for supporting young people in their research proposals, and this could also help in reaching under-represented groups. One young person commented that for some people, “this is their window into research and they’re never going to see it otherwise”. Positions in academia are highly competitive, and experience in the field is invaluable when competing for roles; however, a lot of opportunities for experience are unpaid, which can alienate a large proportion of the student population who may already need to be in some kind of employment alongside their studies. I (Melanie) am currently completing an unpaid research apprenticeship while at university, and am in the fortunate position of being able to dedicate my time outside of my studies to gaining experience rather than working a job. Many people are not in the same privileged position as me, and so increasing the amount of paid opportunities to gain research experience would be invaluable to many students of lower socio-economic status. This could go a long way to levelling the playing field in academia so that people from all backgrounds are able to succeed.

Paid opportunities for research experience could help lower income students build their CVs and research profiles, and allow them to apply for opportunities that might otherwise be inaccessible.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Watson, R., Burgess, L., Sellars, E., Crooks, J., McGowan, R., Diffey, J., Naughton, G., Carrington, R., Lovelock, C., Temple, R., Creswell, C., & McMellon, C. (2023). A qualitative study exploring the benefits of involving young people in mental health research. Health Expectations, 1-14.

Other references

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597.

Ceci. (2022). TikTok usage by age in the UK 2020. Statista.

Coupe, N. (2021). Qualitative co-production: involving people with lived experience in co-analysis of qualitative data. The Mental Elf.

Dixon, S. (2022, March 29). Distribution of Twitter users worldwide as of April 2021, by age group. Statista.

Dixon, S. (2023, February 14). Distribution of Instagram users worldwide as of January 2023, by age group. Statista.

Fløtten, K. J. Ø., Guerreiro, A. I. F., Simonelli, I., Solevåg, A. L., & Aujoulat, I. (2021). Adolescent and young adult patients as co‐researchers: A scoping review. Health Expectations, 24(4).

Harper, D., & Thompson, A. R. (2011). Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners. John Wiley & Sons.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357.

UN General Assembly. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Photo credits

- Photo by Daiga Ellaby on Unsplash

- Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

- Photo by Ivan Aleksic on Unsplash

- Photo by Unseen Studio on Unsplash

- Photo by Josh Appel on Unsplash