Editorial note: Our blog today is written by Professor Kam Bhui from the University of Oxford who is speaking at the #AntiRacistMHResearch event taking place online this evening: How must we disrupt the mental health research system to be anti-racist? It’s different from the usual Mental Elf blogs, but we encourage everyone to read this important piece and join us this evening where Professor Bhui will be exploring race ethics and epistemic justice in research, drawing on his extensive background in research and as the Editor-in-Chief of the British Journal of Psychiatry.

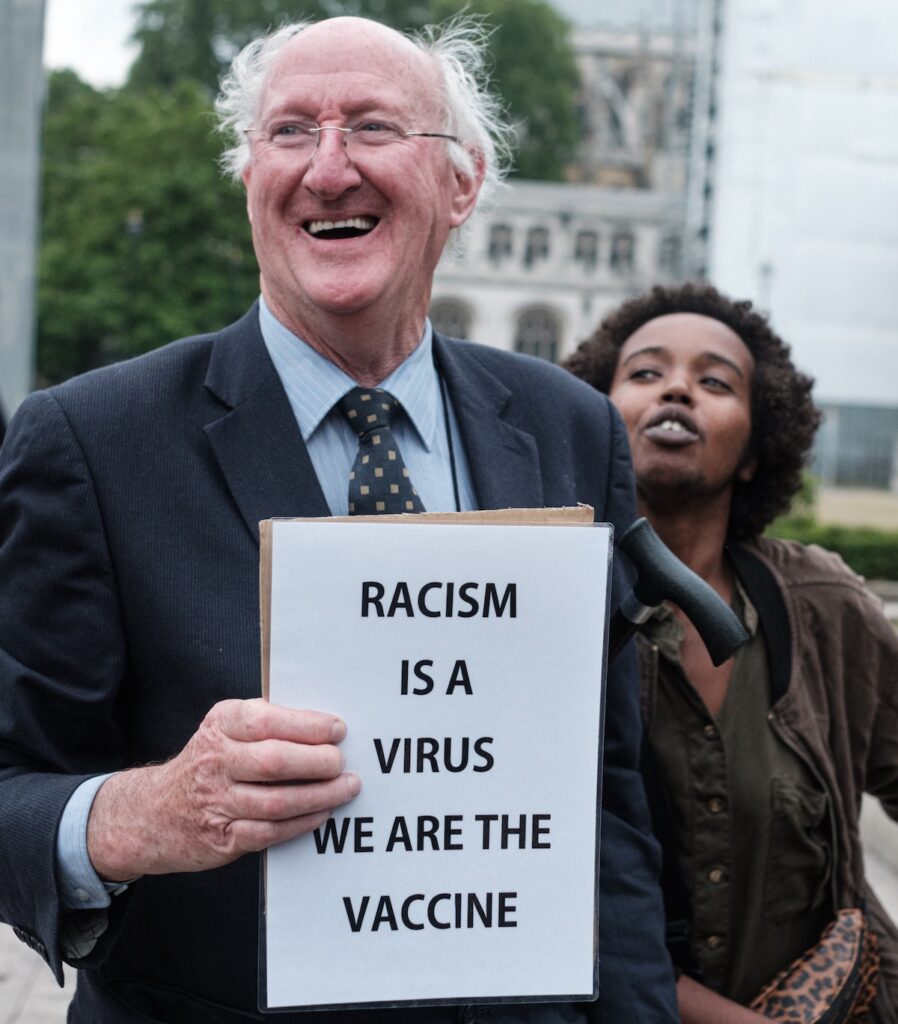

Scientific racism has a long history with numerous examples of poor research that discriminates, discriminatory research of little public value, and misuse of emergent data in order to persuade that racial hierarchies are valid. There is more genetic variation within racial categories than across, so there is no scientific basis that racial groups can or should be distinct in terms of life trajectories or likelihood of illness linked to genes or biology. Despite this, when there are differences of life chances, health, illness, education, employment and criminalisation by specific identities and social positions including race and ethnicity, there is a tendency to conclude that the drivers of illness are related specifically and only to biological notions of race and ethnicity, as in the recent COVID-19 crisis. Clearly the virus is not racist, but people from black and minority ethnic communities, those in minoritised and marginalised positions, and those working in service industry and public services appear to be more likely to be affected. Yes, there may be mediating mechanisms which involve biology, for example, comorbidities or poor immunity, alongside poverty, and social disadvantages; the social and biological mechanisms are not necessarily mutually exclusive or unlinked, as there is plenty of evidence that social adversity and trauma drive poor immunity and long term life chances, even contributing to lost years of life. Adverse childhood experiences, for example, can lead to shortened life expectancy and multiple social and developmental disruptions. We know the social and behavioural determinants of disease and illness drive the prevalence of long term conditions, and that the social context and assets, as well as adversity, shape opportunities and life chances to a far greater extent than biology per se. Indeed, ethnic disparities in the incidence of psychoses, as an example, are largely explained by social and environmental factors.

There is no scientific basis that racial groups can or should be distinct in terms of life trajectories or likelihood of illness linked to genes or biology.

Mental Health care has a specific problem of public perception, stigma, histories of unscientific care reflecting the social and cultural mores and prevailing attitudes of the time. The scientific credibility of psychiatric practice has improved with more research, albeit the paradigms of research are still contested with objections to excessive or any focus on biology and pharmacology, rather than experience-near research based on the humanities, arts, and social sciences. Proposing each modality of research is in opposition to the next is not helpful, in my view, not reflective of the reality of our bio-social existence, influenced by cognition and behavioural responses. Racism in psychiatry and psychology has been especially exposed giving rise to complaints of complicit behaviours of professionals in harmful and discriminatory research and related policy (Fernando, 2018). In part this reflects the co-evolution of psychiatric/psychological sciences at times of prevailing racial thinking in society. Furthermore, despite scientific advances with health research, in order to secure agency and liberty and provide an alternative approach, the service user and survivor movements, and some groups of allied professionals object to the terminology of ‘patient’, ‘mental illness’ and ‘psychiatry’, questioning if psychiatry should be a medical discipline or more of a social science reflecting the social aetiologies of mental illnesses. This is further complicated as emotionality and psychological distress are not pathologies per se, and arise within normative states of life transitions, including dysphoria and distress responses to adversity, trauma and harsh environments. The medicalisation of social distress can thus harm and lead to entanglement of people into the care system, which if insensitive to racial, ethnic, and cultural nuances of assessment, formulation (including diagnostic practices), and care planning, lead to coercive experiences, and escalation of perceptions of risk rather than resilience and recovery (Lipsedge, 1994). This could be a mechanism by which ethnic inequalities in experiences and outcomes of mental illnesses emerge, although rigorous research does confirm that on structured assessments there are differences in incidence of psychoses by ethnic groups (higher in black Caribbean and black African people, South Asians (less so), and migrants and other minorities. Yet, some people with complex needs and sustained distress do benefit from more specialist interventions; striking a balance in debates across these domains is not easy. It is on this background that we must build strategy to tackle racism in practice, policy and research.

Proposing each modality of research is in opposition to the next is not helpful, in my view, not reflective of the reality of our bio-social existence, influenced by cognition and behavioural responses.

The data on racial and ethnic disparities in incidence and outcomes of severe mental illness are long-standing and have shown little shift over 6 decades; these have not always attracted the interpretive vocabulary or motivating explanations that seek to reduce these disparities. Collectively, these differences have been accepted, tolerated, ignored, or normalised, and then even dismissed as ‘wicked problems’ that are too difficult to understand or eradicate. Yet, these differences are known to largely emerge from social and environmental experiences, in part shaped by direct racism, but more likely shaped by structural and institutional influences (Nazroo et al, 2020). The data also show marked differences in use of the Mental Health Act (Halvorsrud et al, 2018) by racial and ethnic groups, findings that the recent independent review of the Act intended to offer remedy. The priorities of the public are clear. A national consultation concluded the following research priorities:

- The impact of racism and adverse care pathways

- Facilitating social support, coping strategies and measures of positivity (e.g. optimism and hope)

- Stigma and societal disadvantages (without reference to racism).

Thus racism is a relevant factor but hardly researched, and structural racism (as a driver of racial and ethnic disparities in experiences and outcomes) has not been a well-supported area of scholarship in the UK. This is in stark contrast with the USA and Canada, where race related and cultural psychiatric research attracts state, federal and research commissioner funding.

Structural racism (as a driver of racial and ethnic disparities in experiences and outcomes) has not been a well-supported area of scholarship in the UK, which is in stark contrast to the USA and Canada.

COVID-19 has altered perceptions and opened up the possibility of better research on race and ethnicity and structural factors, yet with every step forward there are counterflows; the PHE report was delayed and denied initially by government and not published with the main findings and the search for embodied pathologies over-rides the public health enlightened approach for tackling social determinants and structural drives of inequality. Furthermore, the recent report from the race disparity unit seeks to announce that institutional racism does not exist in the UK, whilst striving to address race inequality. These contradictions, narrative-counternarratives, group-anti-groups, polarised and disconnected approaches reflect underlying divergent and politically charged representations of race and ethnicity in our collective social imagination, as well as structural and political forces that drive actions in all spheres of life. We fail to learn, requiring attention to Fanon’s analysis of how the forces of geopolitics and social identity operate as a form of psychopolitics (Hook, 2005).

The recent report from the race disparity unit seeks to announce that institutional racism does not exist in the UK, whilst striving to address race inequality.

Race ethics and research

Why has research, science, evidence, over 60 years not helped? I suggest it is an absence of ethical scholarship and conduct in research practice. This requires radical development in the race ethics skills and vision of those marshalling research policy, commissioning and conduct of research. There are salutary lessons. The above and many examples of disparities being neglected, not improved, or even worsened, amount to fundamental failures of governance, research integrity and ethics.

The famous ‘Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male’ in the USA misled research participants and did not intervene in the evolution of disease in black men. The study continued for 40 years and it was only in 1972 that public outcry and investigations exposed that research participants were not informed of the real purpose of the study or that they were not being treated for an entirely curable disease. This and many other examples of poor research practice, ethical violations, and potential harms to patients and the public have led to significant protections and safeguards in health research. The Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) sets out ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects and is regarded as the most important document in the history of research ethics. The UK approach is set out in the 2017 UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care research. The ESRC proposes six core research ethics principles:

- Research should aim to maximise benefit for individuals and society and minimise risk and harm

- The rights and dignity of individuals and groups should be respected

- Wherever possible, participation should be voluntary and appropriately informed

- Research should be conducted with integrity and transparency

- Lines of responsibility and accountability should be clearly defined

- Independence of research should be maintained and where conflicts of interest cannot be avoided they should be made explicit.

None of these documents specifically refer to racism or race related research, nor to how the scientific (and related policy and communications) process can result in harmful consequences. Thus race-harming or at best race-neglectful conclusions are accepted as valid and continuing harm is done; at the same time public protest about covertly detrimental approaches to health and social care and research are ignored as offering no optimism or positive solutions or even attacking British values. Those with power and resources do not use them for public good, but those without power and resources are expected to solve the problems of race. Alongside, there is political and professional assertions, indignant often, that health systems are not racist, so misrepresenting and at best misunderstanding the meaning of institutional or structural racism. Such interventions close off the possibility that in every day care the options and choices of patients and professionals are governed by social and structural forces, the political economy, and the dominant systems of thinking about race and ethnicity and mental health care. Controversy and divided opinion are common when talking of racism generally, not least as the psychodynamic influences lead to breaks in thinking and linking and fragmented raw emotional responses, born of the survival instincts following generations of oppression (Bhui, 2002). Toni Morrison famously described the problem of racism as being a distraction from doing the work. Yet, the distraction is the very mechanism by which actions are not taken, motivations are undermined, divisions in society are deepened, and inequalities sustained. Political and clinical leadership is lacking and not sustained. Ensuring research is not co-opted to perpetuate racist ideologies requires courage, tenacity, and an exquisite sensitivity to institutional process and practices that are regressive or defensive. History teaches us that we are conditioned to not see poor practice or overtly discriminatory and racist actions or institutional and structural racism as a driver of disadvantage. An eco-social model has been proposed alongside a biopsychosocial model to ensure history and cross-sectoral and ecological learning is not overlooked (Krieger, 2012). To fully understand the cultural influences, a broader lens is required.

Ensuring research is not co-opted to perpetuate racist ideologies requires courage, tenacity, and an exquisite sensitivity to institutional process and practices that are regressive or defensive.

Challenging the status quo

Tylor defined culture as: that complex whole including knowledge, belief, law, arts, morals, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society (Bennett, 2015). Culture is learnt, shared, social, whole and integrated, as well as enacted individually and in family units. Although criticised for being Eurocentric and perhaps devoid of class and poverty as relevant influences, the definition poses numerous methods problems for research that claims to address culture, as opposed to race or ethnicity. The different layers of culture, ethnicity and race thus require overlapping but distinct concepts, analyses, research questions, and designs. The notions of institutional racism and societal racism also need unpacking. These are not trivial distinctions, yet if institutions setting policy and governance functions fail to understand or embrace these ‘known knowns’ it is difficult to build research to uncover what we are yet to learn and adopt more progressive research designs and traditions. Confidence in institutions is undermined if research continues to generate conclusions which seem to overlook harms of intervention to specific groups, neglect of care to specific groups, or – I argue – where research cultures and commissioning systematically ignore race, ethnicity, culture, religion, migration and histories of persecution, minoritisation and racialisation by:

- Emphasising public good means the majority benefit

- Seeing research on race and minorities as divisive (contrary to social or immigration policy) or financially unjustified if per capita benefits are not demonstrable compared with research on majority populations

- Not recruiting samples that are representative of the intended beneficiaries where all citizens are given due weight, and ignored exceptions drive inequalities

- The design does not consider markedly different notions of health and illness, wellbeing and recovery, and even what constitutes research as part of the social contract between state and citizens. Research humility is often lacking in ambitious designs and programmes that claim superlative knowledge: for example, when research methods and design:

- Ignore or demonstrate poor understanding of race and racism, and ethnic, linguistic and cultural variations in experiences and outcomes of mental illness.

- Show an absence of race and racism from ethical consideration, training and guidelines.

- Lack scholarship in race ethics and in ethnic disparities in race and ethnicity in both social and health care, and in other industries.

- Give little or no attention to health beliefs and social status, poverty, and social position and identity contexts, or kinship.

- Ignore discrimination and racism – direct and institutional and societal. Each need careful evaluation within such paradigms, and careful framing so as not to reinforce stereotypical racist notions of inferiority and superiority patterned by race. History shows science is not neutral nor value free.

- Recognise that research findings that do not effect change are unethical, so all research should demonstrate progressive impact on the field of practice and research and the intended beneficiaries.

A lack of attention to these issues is unethical if research is directly seeking to tackle inequalities or recruit marginalised populations, or testing hypotheses about inequalities and marginalised groups. Other research that seeks to not overlook or cause harm must adopt the principles of cultural safety alongside cultural humility and carefully apply an ethical lens to ostensibly race-neutral processes. The potential for misuse of research data should be engrained in the work of scientists.

Research cultures and commissioning systematically ignore race, ethnicity, culture, religion, migration and histories of persecution, minoritisation and racialisation.

Ethics committees

Ethics committees and commissioning of research must address these and some more issues:

- Vocabularies and framing of research to produce actions of benefit and reduce harms, from populations to specific groups.

- Experience-near legitimacy and exceptions to the majority views should be designed into the research to mitigate further inequalities. Indeed, a race impact assessment should be undertaken within the proposed research as an early indication of harms or lack of benefit, with stop go rules as is common in feasibility work or internal pilots. This could include vocabularies, methods to improve recruitment, methods to better involve people in research and benefit from it.

- There should be other public good from research in improving health literacy, the race-ethics skills of research staff.

- The research should up-skill peer researchers with carefully constructed career trajectories and contracts that demonstrate parity and equal power.

- We need case studies of problematised and good practice to deepen our understanding of how racism operates and how it can be dismantled through race-ethics frameworks. This requires a range of methods and approaches, and innovations.

- Good research integrity and research cultures are critical. Regrettably, research cultures driven by metrics and performance rather than scholarship impact negatively on the beneficiaries and on the capacity for research institutions to respond to inequalities.

- Ethical guidance in university recruitment and performance reviews are necessary, as are alternative models of ethical research practice and conduct, with research that is embedded in communities and localities.

- There are methods that improve recruitment and retention of marginalised groups in research; these methods harness experience data and leave participants as empowered and informed citizens, where the research impacts on the local health and social systems. Deployment of multiple methods should be a standard component of all research, especially where the failings of one method can be overcome with another.

- There should be regular independent review and scrutiny; proportionate to complexity and risk of harms associated with specific designs and stages of research. This could consider:

- What area of race and ethnicity scholarship is being advanced by a specific study, in terms of methodology/outcome measurement, as well as new knowledge, and how this knowledge impacts on either clinical care or steps to clinical care; or public health or steps towards improving public health; or addressing social and cultural determinants of poor health, or research on new methods to achieve the other objectives?

- What is the lasting legacy of each research project for participants, for local communities, for research and training and professional institutions?

- What are the counterpart actions for medical and social care, physical health care generally, emergency care, perinatal care, child protection, social and public health, with implications on other sectors like criminal justice, education, and immigration policy and practice?

Good research integrity and research cultures are critical. Regrettably, research cultures driven by metrics and performance rather than scholarship impact negatively on the beneficiaries and on the capacity for research institutions to respond to inequalities.

Three potential big actions for organisations

- Recognise the history and legacy and commit to presenting an honest and optimistic way forward (celebratory events, networks events, art and historical events, more engaging informative websites, buildings, representative of the diverse workforce and population)

- Consider changes to curricula and all scholarship activities, including around research and delivery of research

- Establish progressive recruitment, retention, and workforce supports, including leadership development.

Organisations serious about becoming anti-racist must recognise and respond to the history and legacy, consider changes to curricula and all scholarship activities, and establish progressive workforce policies.

Specific actions

1. Guidance and best practice

Establish best practice in recording ethnicity (race, ethnicity, identity, acculturation and migration, religiosity, intersectional identities) and provide guidance for researchers and NHS practice; this is especially important to collect better routine data sets for research and commissioning guidance. Some journals and ONS provide guidance for data collection and publications, yet we should be able to propose flexible schema for research reflective of the hypotheses and types of research questions and relevant participants. This necessarily involves learning modules at relatively basic, moderate and advanced levels. Similar guidance might be provided for students and for projects within ARCs and BRCs, NHS Trust approvals, as well as institutional and national ethics boards. An important element of this would include understanding interactions between age, gender, sexuality, race and ethnicity. Specific ethnic definitions, or race or migrant based definitions, may be necessary if hypotheses require these. Self-defined definitions of identity should be sought alongside master categories, which although conventional, tell us little about a person’s life story or individual adaptations and resilience.

2. Recruitment into research

Some guidance is available, and research exists testing different approaches but more needs to be done to ensure adequate representation. A coalition might develop best practice, complete rapid reviews, and take forward recommendations. There should be a process for voicing and tackling the dilemmas encountered by researchers in ensuring equity, including additional cost. Again, where the research hypotheses require specific recruitment quotas, the methods must be explicit; in general all research (and practice) should show credible plans for improving recruitment from marginalised groups. This could even become part of stop-go rules for trials and a focus for feasibility and pilot studies.

3. Routine clinical and research data sets used by partners

Are they fit for purpose in terms of recording and retrieving records for planning research, commissioning, or even service provision? A rapid review of systems would provide the necessary assurances or make explicit urgent proposals to remedy current failings. A suitable high quality platform or archive of maintained data is necessary, which is linked and continues to evolve.

4. Specific methodological issues

Cultural adaptation of interventions and outcomes requires multiple methodologies for exploring cultural perspectives (qualitative methods, ethnography, participatory methods etc). This should be pursued before hypothesis testing. Such methods recognise that defining a problem more accurately and ensuring the questions are cognisant of patient/public experiences and expectations is likely to improve relevance and validity, rather than be a hurdle.

5. Interdisciplinarity

This is essential but can be a hurdle if it takes more time and resources to ensure balanced partnerships and sufficient resources for everyone’s input, and to ensure all input is equally valued. Creating interdisciplinary research groups with equity in mind, will itself bring to the fore markedly distinct and divergent narratives of race, ethnicity, and EDI (equality, diversity and inclusion), and what solutions might be proposed.

6. Workforce representation

Actions need to improve recruitment of more minority early career researchers, retain experienced researchers and staff and fair promotion policies and practices: these need careful inspection of existing processes and procedures, and for all to take governance responsibilities. Guidance should apply to the NHS, universities, and partner organisations, and require a coherent and widely accepted set of values and policies and procedures that are monitored. It is also imperative that good communication and feedback involve hearing the views of staff (in all settings), and grievance and complaint are actively reviewed, monitored, with processes to ensure improvements follow when needed.

7. Scholarship

Studies should be more explicit about their inclusion or exclusion of diverse populations, and coalitions should encourage more scholarship, both in terms of courses/curricula as well as research that specifically seeks to better understand the drivers of inequalities and solutions and evolve better methodologies. This is a challenging, multi-systems, and cross-organisation ambition. Regrettably, scholarship on inequalities and racism and health care are not seen as sufficiently important or central to university strategy, often giving way to employment and recruitment and bullying and harassment policies that serve a defensive function for the organisation; rather than a progressive remedy to a widespread systems problem.

8. Committees and governance

Anti-racism and EDI actions should be mainstreamed and retained in core committee functions, not devolved to sub-groups or committees whose experience and expertise are harvested and risk being ignored if the core committee is not part of the journey and abrogate responsibilities. Chairs of committees are personally responsible for good governance as are officers of any organisation. They should be engaged in ongoing anti-racism and EDI conversations and development as part of the scholarship journey of committees and their respective institutions.

Chairs of committees and officers of organisations should be engaged in ongoing anti-racism work and equality, diversity and inclusion conversations.

#AntiRacistMHResearch – How must we disrupt the mental health research system to be anti-racist?

Watch Kam Bhui talk about Research Integrity and Race Ethics at our live streamed #AntiRacistMHResearch webinar at 5.30-7.00pm BST on Tuesday 13th April, organised in partnership with the University of Liverpool Student Psychiatry Society and the McPin Foundation.

References

Fernando S. (2018) Institutional Racism in Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology: Race Matters in Mental Health. Palgrave Macmillan. 2018. £49.99 (pb). 232 pp. ISBN 9783319873800

Lipsedge M. (1994) Dangerous stereotypes. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry 1994;5(1):14-19. doi: 10.1080/09585189408410894

Nazroo, J.Y., Bhui, K.S. and Rhodes, J. (2020), Where next for understanding race/ethnic inequalities in severe mental illness? Structural, interpersonal and institutional racism. Sociol Health Illn, 42: 262-276. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13001

Halvorsrud, K., Nazroo, J., Otis, M. et al. (2018) Ethnic inequalities and pathways to care in psychosis in England: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 16, 223 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1201-9

Hook D. (2005) A Critical Psychology of the Postcolonial. Theory & Psychology. 2005;15(4):475-503. doi:10.1177/0959354305054748

Bhui, K. (Ed.). (2002). Racism and mental health: Prejudice and suffering. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Krieger N. (2012) Methods for the Scientific Study of Discrimination and Health: An Ecosocial Approach American Journal of Public Health 102, 936_944, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544

Bennett T. (2015) Cultural Studies and the Culture Concept, Cultural Studies, 29:4, 546-568, DOI: 10.1080/09502386.2014.1000605

Photo credits

- Photo by Yasin Yusuf on Unsplash

- Photo by Alex Block on Unsplash

- Photo by Paweł Czerwiński on Unsplash

- Photo by Dan Dimmock on Unsplash

- Photo by kevin turcios on Unsplash

- Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash

- Photo by Eden Constantino on Unsplash

- Photo by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona on Unsplash