With increasing suicide deaths since 2000 in the USA, suicidal experiences (i.e. thoughts, plans, attempts and deaths) are a major health concern (Ahrnsbrak et al., 2017; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2016).

Whilst working with people with suicidal experiences, clinicians frequently report feelings of stress, anxiety, incompetence, frustration and anger, along with helplessness, discouragement, sadness and guilt (Ellis et al., 2018; Soulié, et al., 2018). Evidence has suggested such emotional reactions can occur early on in psychotherapy (Perry et al., 2013) and predict service user’s suicidal ideation and behaviours (Barzilay et al., 2018; Hawes et al., 2017; Yaseen et al., 2017).

The therapeutic alliance is when a therapist and service user work together to agree on therapeutic goals and tasks, and also develop a bond (Bordin, 1979). A wealth of evidence suggests that the therapeutic alliance is a well-known transdiagnostic facilitator of positive change and outcomes across different therapeutic modalities (Flückiger et al., 2018; Horvath et al., 2011).

Service users with suicidal ideation frequently experience hopelessness (Beck et al., 1990) and negative views of interactions with others (Van Orden et al., 2010), which could lead to reduced trust and liking from the clinician’s point of view. In turn, clinician’s negative emotions may be expressed by less empathic communication, avoidance and unconscious dismissal of the service user (Hutchinson & Jackson, 2013), which could negatively impact on the therapeutic alliance (Ulberg et al., 2014). Conversely, a good therapeutic alliance may act as a buffer to clinician negative reactions and reduce suicidal ideation (Perry et al., 2013).

The current study by Barzilay et al. (2020) therefore aimed to:

examine the associations between clinicians’ negative emotional responses, service user’s and clinicians’ perceptions of the therapeutic alliance, and service user’s suicidal ideation.

They also:

tested whether service user’s and clinicians’ perceptions of the therapeutic alliance mediate the associations between clinicians’ emotional responses and service user’s short‐term suicidal ideation.

Does the therapeutic alliance explain a relationship between clinician emotional reactions and suicidal ideation in service users?

Methods

Service users and clinicians were recruited from psychiatric outpatient services in New York City, USA. Several measures were completed following the first appointment between the clinician and service user.

Clinicians and service users both completed demographic information.

Clinicians completed:

- Clinician assessment of service user’s diagnosis using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)

- Clinician assessment of service user suicidal ideation and attempt history

- Therapist Response Questionnaire-Suicide Form (TRQ-SF), which measures clinician emotional response

- Working Alliance Inventory (WAI), which measures the clinician’s perspective of the therapeutic alliance.

Service users completed:

- Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), which was used to measure severity of symptoms related to mental health problems

- Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS), which measures the severity of service user’s suicidal ideation

- Working Alliance Inventory (WAI), which measures the service user’s perspective of the therapeutic alliance.

Results

Sixty-one clinicians took part, who were mainly psychiatry trainees in their third year, Caucasian, born in the USA, identified as female and had an average age of 32 (range 26 to 49). Clinicians favoured a range of psychotherapeutic approaches, including psychodynamic, cognitive/behavioural, integrative, humanistic/supportive and interpersonal.

There were 378 service users, who were mostly Caucasian and female, with a primary diagnosis of depression and a mean age of 39. One third of participants had attempted suicide previously.

The study found:

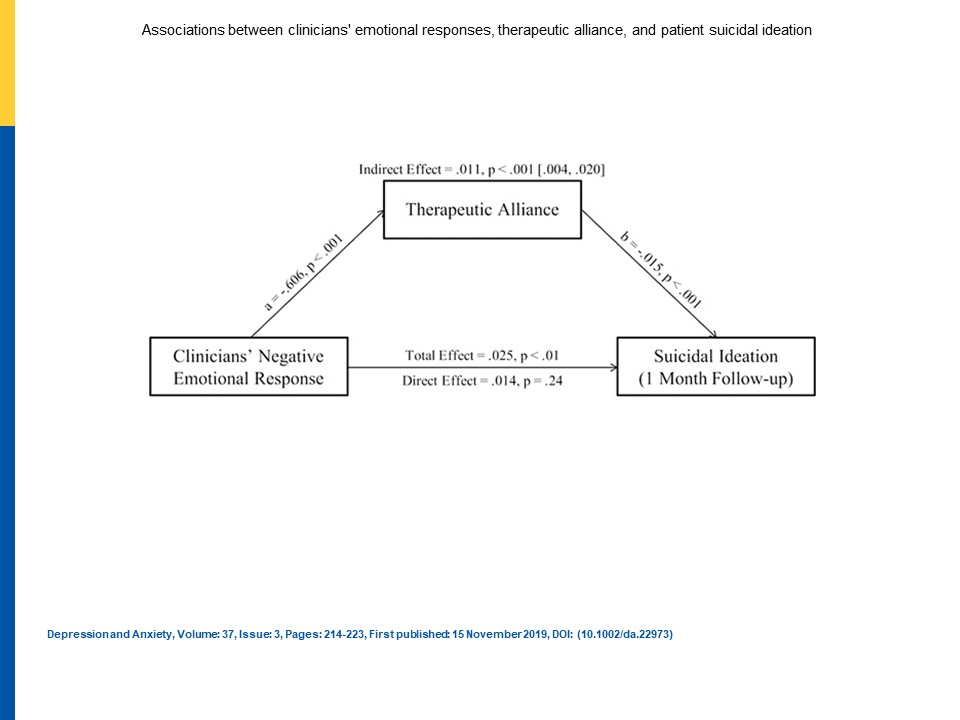

- Clinicians’ negative emotional responses were associated with a poor therapeutic alliance from both service user and therapist perspectives.

- More severe suicidal thoughts at one month follow up were associated with clinician negative emotional responses, a poor service user perception of the therapeutic alliance and previous suicide attempts.

- The therapeutic alliance during the first session, as perceived by the service user, mediated the relationship between clinician negative emotional response and suicidal ideation at one month follow up. However, there was no direct effect of clinician response on suicidal ideation. In other words, when clinicians felt more negatively towards service users, this did not impact directly on suicidal ideation severity. However, when service users perceived the therapeutic alliance as weak, this predicted more severe suicidal ideation one month later.

- In contrast, the clinician view of the initial therapeutic alliance did not significantly mediate such a relationship. Instead, there was a small direct effect of overall clinician emotional response on suicidal ideation at one month follow up.

- Furthermore, the mediation model was applied to three components of clinician response, namely, affiliation, distress and hope. Service user perception of the therapeutic alliance indeed significantly mediated the relationship between affiliation distress and hope respectively, and severity of suicidal ideation. None of these components directly influenced severity of suicidal ideation. This means that clinician responses alone did not impact on suicidal ideation severity, but did influence the service user’s perception of the therapeutic alliance, which negatively impacted on suicidal ideation.

When service users perceived the therapeutic alliance as weak, this predicted more severe suicidal ideation one month later. View full size diagram.

Conclusions

The study investigated whether the clinician and service user perception of the therapeutic alliance mediated the relationship between clinician emotional reactions and client severity of suicidal ideation. Overall, only the service user’s view of the therapeutic alliance significantly mediated such a relationship; if clinicians experience negative thoughts and emotions toward a service user, service users may perceive the therapeutic alliance more negatively, which was related to more severe suicidal ideation.

The authors conclude that clinician awareness of their thoughts and feelings is an essential component in therapeutic interactions. Training and support is needed to ensure that mental health professionals have the ability to reflect on and manage their emotional responses. In turn, this will facilitate the development of the therapeutic alliance, which will lay the foundation for the clinician and service user to work collaboratively in reducing suicidal thoughts.

Clinicians’ awareness of their thoughts and feelings is essential to therapeutic interactions.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the current study is that clinicians and service users were recruited from a naturalistic setting, namely, psychiatric outpatient centres. However, some bias could have been introduced by the sample at follow up time-points. For instance, service users who completed the follow up measure were more likely to be older and have been in education for longer.

Internal reliability was good to excellent for all of the outcome measures, which instils confidence in the measures used. However, the therapeutic alliance was developed using both psychotherapy and psychopharmacological treatments and no details were provided as to what psychopharmacological treatments involved. As there was such a broad range of approaches and a large proportion of clinicians were qualified psychiatrists, bias in the clinician’s approach to developing a therapeutic alliance could have been introduced. In order to mitigate such intervention bias, studies should provide details of and adhere to a specific therapy manual. Furthermore, future studies should include more clinicians from other mental health backgrounds, e.g. clinical psychology and nursing, to enable greater generalisability.

Although the authors should be commended for recruiting a large sample, the effect sizes in the mediation model were small. The sample size may offer an alternative explanation to the mediation model findings, more specifically, significant findings are more likely to be detected in large sample sizes. Therefore, it could be that suicidal ideation outcomes may only be impacted by negative clinician emotions, albeit indirectly via the therapeutic alliance, in a small number of people. As this was the first study to examine such relationships, further studies need to be conducted to see if the findings are supported and whether other factors, for instance clinician and service user characteristics such as age, gender identity and ethnicity may also be affecting clinician emotional reactions, the therapeutic alliance and subsequent suicidal ideation.

Key limitations include: no standardised therapy manual, over-representation of clinicians from a psychiatry background and small effect sizes.

Implications for practice

The study suggests that further training and competency requirements may be important in assisting clinicians to reflect on and manage their emotional responses when working with service users with suicidal experiences. Such skills will equip clinicians to develop a more robust therapeutic alliance with service users and in turn improve therapeutic outcomes of suicidal ideation. Furthermore, reflections on emotional responses and barriers to developing the therapeutic alliance should be discussed in clinical supervision.

There are several psychological interventions which are designed to improve both the therapeutic alliance and service user’s suicidal experiences. Such interventions include:

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBSP; Gooding et al., 2020; Haddock et al., 2019; Pratt et al., 2016)

- Dialectic Behavioural Therapy (DBT; Chapman & Rosenthal, 2016)

- Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS; Jobes, 2012)

- Recognition, acceptance, investigation, and non-identification (Ellis et al., 2018).

It is recommended that service users with suicidal experiences are given more opportunities to access these psychological interventions.

Clinicians should be given training and support to reflect on and manage their emotions, so that they can strengthen the therapeutic alliance with people who are at risk of suicide.

Statement of interests

Charlotte Huggett is currently the Trial Manager of the CARMS (Cognitive AppRoaches to coMbatting Suicidality) trial, which is examining the efficacy of a Cognitive Behavioural Suicide Prevention (CBSP) Therapy for people experiencing non-affective psychosis and suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Charlotte previously worked as a Project Coordinator on a pilot trial assessing the feasibility and acceptability of CBSP therapy for people on mental health inpatient wards with suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Furthermore, Charlotte is currently undertaking an MPhil examining the relationship between the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and suicidal experiences by conducting a systematic review and empirical study, both of which are currently being written up for publication.

Links

Primary paper

Barzilay S, Schuck A, Bloch‐Elkouby S, et al. (2020) Associations between clinicians’ emotional responses, therapeutic alliance, and patient suicidal ideation. Depress Anxiety. 2020; 37: 214– 223. [PubMed abstract]

Other references

Ahrnsbrak R, Bose J, Hedden SL, et al. (2017) Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Retrieved from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH‐FFR1‐2016/NSDUH‐FFR1‐2016

Barzilay, S., Yaseen, Z. S., Hawes, M., et al. (2018) Emotional responses to suicidal patients: Factor structure, construct, and predictive validity of the Therapist Response Questionnaire‐Suicide Form. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 104. [PDF]

Beck AT, Brown G, Berchick RJ, et al. (1990) Relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: A replication with psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147(2), 190–195. [ABSTRACT]

Bordin ES. (1979) The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 252. [PDF]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Web‐based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). from National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Chapman, A. L., & Rosenthal, M. Z. (2016). Managing therapy‐interfering behavior: Strategies from dialectical behavior therapy. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Ellis TE, Schwartz JAJ, & Rufino KA (2018) Negative reactions of therapists working with suicidal patients: A CBT/Mindfulness perspective on “countertransference”. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 11, 80–99. [PDF]

Flückiger C, Del Re A, Wampold BE, & Horvath AO (2018) The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta‐analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55, 316–340. [PUBMED ABSTRACT]

Gooding PA, Pratt D, Awenat Y. et al. (2020) A psychological intervention for suicide applied to non-affective psychosis: the CARMS (Cognitive AppRoaches to coMbatting Suicidality) randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Psychiatry 20, 306 [PDF]

Haddock G, Pratt D, Gooding P, et al. (2019) Feasibility and acceptability of suicide prevention therapy on acute psychiatric wards: Randomised controlled trial. BJPsych Open, 5(1), E14. [PDF]

Hawes M, Yaseen Z, Briggs J, & Galynker I (2017) The modular assessment of risk for imminent suicide (MARIS): A proof of concept for a multi‐informant tool for evaluation of short‐term suicide risk. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 72, 88–96. [PUBMED ABSTRACT]

Horvath AO, Del Re AC, Flückiger C, & Symonds D. (2011) Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9–16. [PUBMED ABSTRACT]

Hutchinson M, & Jackson D. (2013) Hostile clinician behaviours in the nursing work environment and implications for patient care: A mixed‐ methods systematic review. BMC Nursing, 12(1), 25. [PDF]

Jobes DA. (2012) The collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS): An Evolving evidence‐based clinical approach to suicidal risk: Collaborative assessment and management of suicidality. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 42(6), 640–653. [PUBMED ABSTRACT]

Soulié, T., Bell, E., Jenkin, G., Sim, D., & Collings, S. (2018). Systematic exploration of countertransference phenomena in the treatment of patients at risk for suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 1–23. [PUBMED ABSTRACT]

Ulberg R, Amlo S, Hersoug AG, et al. (2014) The effects of the therapist’s disengaged feelings on the in‐session process in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 440–451. [PUBMED ABSTRACT]

Perry JC, Bond M, & Presniak MD. (2013) Alliance, reactions to treatment, and countertransference in the process of recovery from suicidal phenomena in long‐term dynamic psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 23(5), 592–605. [PUBMED ABSTRACT]

Pratt D, Gooding P, Kelly J, et al. (2016) Case formulation in suicidal behaviour. In: Tarrier N. & Johnson J. eds. Case Formulation in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2nd Edition. East Sussex: Routledge, 265-283

Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, et al. (2010) The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. [PUBMED ABSTRACT]

Yaseen ZS, Galynker II, Cohen LJ, & Briggs J. (2017) Clinicians’ conflicting emotional responses to high suicide‐risk patients‐Association with short‐term suicide behaviors: A prospective pilot study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 76, 69–78. [PUBMED ABSTRACT]

Photo credits

- Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

- Photo by Danielle MacInnes on Unsplash

- Photo by Kyle Glenn on Unsplash

- Photo by Russ Ward on Unsplash

- Photo by Riccardo Annandale on Unsplash