More than 5,ooo suicides were registered in England alone back in 2022 (Samaritans, n.d.). That’s more than 14 people every day of the year in England who took their own lives. Each with their own individual tragic story. What’s more, this is the number of registered suicides, so the actual number of people who died by suicide is likely to be higher.

It is said that healthcare workers are at a higher risk of suicide than any other profession (NHS Employers, 2024), potentially due to the long-term psychological impacts on healthcare staff caused by increased burnout and compassion fatigue (Sullivan & Germain, 2020).

For healthcare professionals it can be difficult to navigate a colleague’s suicide due to the complications surrounding grief such as professional identity (e.g., the notion that healthcare workers should be resilient and impervious to work-related stresses) and workplace culture (e.g., potential stigmas surrounding suicide leading to bereaved individuals fearing judgement, thus causing them to hide their feelings; Causer et al., 2022).

Due to the complexity surrounding suicide within healthcare professions, the need to broaden suicide research to incorporate organisational and managerial factors has been emphasised (Causer et al., 2022). Further, just by knowing someone who died by suicide can impact an individual through trauma, depression, complicated grief and possible substance misuse which could last years (The Alliance of Hope for Suicide Loss Survivors, 2024). Thus, postvention has been introduced into the workplace.

Postvention can be defined as activities that reduce risk and promote healing after a suicide death (The Alliance of Hope for Suicide Loss Survivors, 2024), including communicating the loss, memorial services and providing information for support. Effective postvention support is very important for workers as it can have a positive impact on recovery and reduce the likelihood of developing mental health difficulties and suicidal feelings (Riley, 2023). Additionally, NHS Employers (2024) suggest that healthcare organisations with comprehensive wellbeing support experienced lower staff turnover and higher satisfaction levels. These research findings highlight the complexity and significance of supporting healthcare staff after a colleague’s suicide.

Building upon existing research, Spiers et al. (2024) aimed to deepen our understanding of postvention experiences and improve targeted interventions for staff well-being and organisational resilience in the aftermath of a colleague’s suicide, using grounded theory.

While models of postvention support have been developed for clinicians after patient suicide, no models exist to guide the delivery of postventions after a colleague’s suicide. Spiers et al. (2024) used grounded theory to address this gap in our knowledge.

Methods

The researchers used a method called grounded theory to study how NHS staff support colleagues after a coworker’s suicide. Grounded theory is the development of a theory/hypothesis based on collected data which enables researchers to uncover social relationships and behaviours of groups from real life experiences (Noble & Mitchell, 2016).

Participants were recruited through NHS Trusts, social media, and word of mouth. Twenty-two participants took part in the interviews, which were conducted via telephone or video call. The aim of these interviews was to understand the different experiences of supporting colleagues after the suicide of a co-worker.

Upon gathering sufficient information, Spiers et al. (2024) developed a theory on how to handle post-suicide support in healthcare settings.

Results

The majority of participants identified as female (n = 18), White British (n = 21), worked as nurse managers (n = 9), and had experienced one suicide within a 6 months to 10 year period (n = 14).

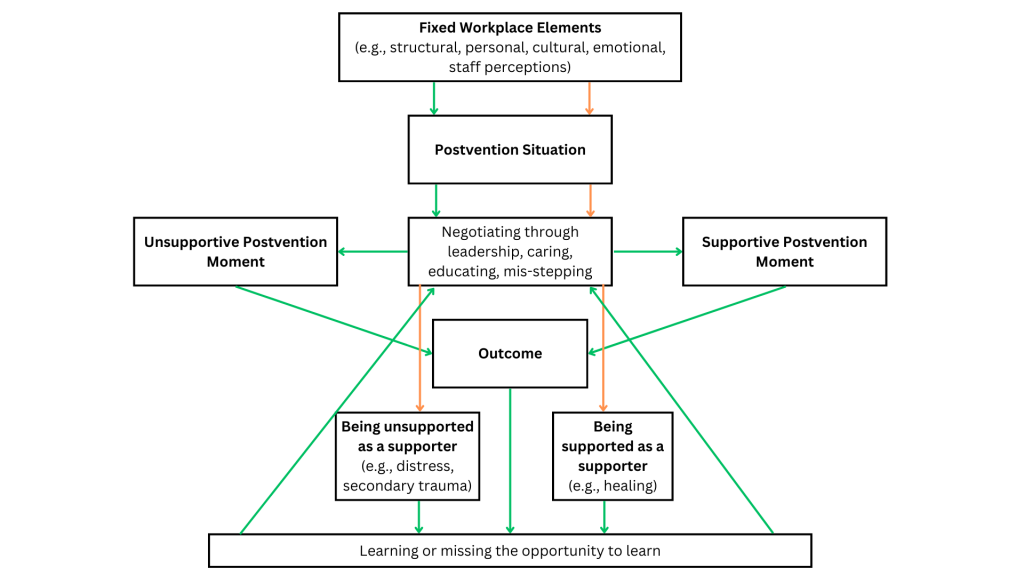

Based on analysis of the interviews, the authors developed a grounded theory of negotiating postvention situations (see Figure 1), starting with the influence of fixed workplace elements, which were outside of a staff member’s control, yet played a key role in shaping their responses following a colleague’s suicide. These elements could be both enabling and disabling:

- Structural (covering the actual workplace):

- Enabling elements: clear protocols for intervention and adequate staffing, which facilitate effective support provision.

- Disabling elements: lack of capacity, inadequate resources and lack of training, hinder staff’s ability to respond promptly and deliver necessary support.

- Personal:

- Enabling elements: role seniority and experience in mental health, can empower individuals to cope effectively when supporting.

- Disabling elements: lack of experience and personal reactions may worsen distress.

- Cultural:

- Enabling elements: supportive workplace cultures enabling help-seeking behaviours.

- Disabling elements: stigma and lack of cohesion discourage support seeking.

- Emotional:

- Covers both the provision of emotional support and the intensity of distress experienced.

- Staff perceptions:

- Can either build confidence and resilience or reduce trust and hinder coping efforts.

[View full size image] Spiers et al.’s (2024) model of postvention support, adapted from the original paper with the following note: “The green arrows indicate the situation/behaviours/outcomes of the supporters, whereas the orange arrows refer to the situation and behaviours of those supporting the supporters.”

Understanding and addressing these elements are crucial for optimising support systems and promoting staff well-being in the aftermath of a colleague’s suicide. These elements influence how supporters and those supporting supporters can negotiate postvention situations, which can involve the following:

- Leadership:

- Sets the tone by acknowledging the death and offering compassionate communication.

- Caring:

- Creating a supportive environment where staff feel heard and valued, promoting open discussions, emotional support, and self-care exercises.

- Educating:

- Plays a crucial role in equipping staff with coping skills, recognising signs of distress, and pushing for changes in policies and procedures.

- Mis-stepping:

- Navigating missteps, such as silence surrounding suicide and doing too much, can reduce trust.

By addressing the above components, healthcare organisations can support staff effectively through the aftermath of a colleague’s suicide.

This leads to either providing a supportive or unsupportive postvention moment. Postvention moments following a colleague’s suicide are important for testing the effectiveness of supporters. Supportive moments (e.g., memorials, togetherness) promote healing and resilience among staff, whereas unsupportive moments (e.g., lack of emotional congruency, silence) may all deem the postvention ineffective.

Finally, being supported as a supporter significantly impacts well-being. Adequate support validates emotions and offers reassurance, often via managers and supervisors. In contrast, lacking support intensifies distress, leading to isolation and burnout. Unsupported supporters may experience secondary trauma (indirect experience of or exposure of a traumatic event including descriptions of trauma), affecting both mental health and job performance.

Spiers et al. (2024) found that multiple factors determine the effectiveness of postvention including fixed workplace elements, negotiating the postvention through leadership, caring, education and mis-stepping, supportive/unsupportive postvention moments and being supported/unsupported as a supporter.

Conclusions

Postvention experiences, whether supportive or unsupportive, offer invaluable opportunities for organisational learning. Reflecting on these experiences enables the identification of effective strategies and areas for improvement in supporting staff through similar challenges. Missed opportunities to learn, such as not addressing staff needs adequately, highlight areas for organisational growth and the importance of proactive support systems in promoting staff well-being.

By being able to reflect on postvention situations following a colleagues suicide, either supportive or unsupportive, will identify areas for improvement, missed opportunities and promote staff wellbeing.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

- Grounded theory methodology: The study’s use of grounded theory allows for the development of a theory directly from the data, ensuring that findings are closely aligned with participants’ real-life experiences of delivering postvention support, therefore increasing validity.

- Diverse participant pool: Including 22 participants from various NHS roles enhances the study’s scope, providing a deeper understanding of postvention experiences and potentially the ability to apply this theory to a broader population.

- Simultaneous data collection and analysis: Conducting data collection and analysis at the same time enables the researchers to improve their focus and adjust interview questions based on developing themes, improving the relevance of the findings.

Limitations

- Recruitment challenges: Difficulties in recruiting participants who experienced significant postvention challenges may result in an overrepresentation of positive experiences, potentially limiting the study’s generalisability. Further, most participants were White British which means that Black and other minority ethnic populations are not represented; a group which the researchers agree make up a large part of the NHS workforce (NHS England, 2023).

- Limited scope: Focusing solely on NHS staff within England may restrict the applicability of the findings to other healthcare systems and organisational cultures, again reducing their generalisability.

- Reliance on self-reported data: The study’s reliance on self-reported data through interviews may introduce bias, as participants may present themselves in a favourable light or not fully recall all details of their experiences, potentially affecting the validity of the findings.

Although Spiers et al. (2024) heavily contributed to postvention understanding, the study may be difficult to generalise due to solely using NHS staff’s experiences and a majority of White British participants, limiting the applicability to Black and Minority Ethnic colleagues who make up a large part of the NHS.

Implications for practice

As an individual working in the NHS, specifically within mental health, I am very aware of the demanding and emotionally taxing nature of our roles. Each day, many employees are confronted with challenging situations that require us to deal with difficult emotions while providing the best possible care for our patients and colleagues. The experience of supporting colleagues after a colleague’s suicide is particularly difficult, as it involves balancing our own emotional reactions with the need to support others who are also struggling.

Through my work, I have experienced firsthand the toll that suicide can have on individuals’ morale and well-being, and I understand the importance of implementing effective support strategies to mitigate the impact of such tragedies. By addressing the findings of this study in practice, we can create a more supportive and resilient work environment for ourselves and our colleagues, ultimately improving the quality of care we provide to our patients.

- Development of structured postvention protocols: Clear guidelines and procedures are essential to guide staff in effectively supporting colleagues after a suicide. Implementing structured postvention protocols can alleviate some of the emotional burden on staff and ensure that support is provided in a prompt and effective manner.

- Strengthening organisational support structures: Organisational support structures, including peer support programs and appropriate facilities, play a crucial role in aiding postvention efforts. Ensuring that these support systems are readily accessible and well-advertised can encourage staff to seek help when needed.

- Promoting open communication and reducing stigma: Open communication about mental health and suicide is essential for reducing stigma and encouraging help-seeking behaviours among staff. Leadership should lead by example, showing empathy and understanding, to create a supportive environment where staff feel comfortable discussing their experiences and seeking support without fear of judgment.

Addressing the implications of this study in practice can lead to a more supportive and resilient healthcare environment. By implementing structured postvention protocols, strengthening support structures, and promoting open communication, healthcare organisations can better support their staff in the aftermath of a colleague’s suicide, ultimately improving patient care and staff well-being. Although postvention strategies have been developed for supporters to use following the suicide of a colleague, as of present, the postvention theory developed by Spiers et al. (2024) has yet to be tested or reviewed in practice. However, with time, hopefully the findings will positively contribute to developing effective postvention situations.

Implementing structured protocols, enhancing training, strengthening support, and promoting open communication are all steps that can be implemented within workplaces to better support staff wellbeing after a colleague’s suicide.

Statement of interests

I declare that the blog was written in absence of any commercial or financial conflicts of interest.

Links

Primary paper

Spiers, J., Causer, H., Efstathiou, N., Chew-Graham, C. A., Gopfert, A., Grayling, K., … & Riley, R. (2024). Negotiating the postvention situation: A grounded theory of NHS staff experiences when supporting their coworkers following a colleague’s suicide. Death Studies, 1-11.

Other references

Causer, H., Spiers, J., Efstathiou, N., Aston, S., Chew-Graham, C. A., Gopfert, A., … & Riley, R. (2022). The impact of colleague suicide and the current state of postvention guidance for affected co-workers: A critical integrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11565.

NHS Employers. (2024, February 16). Evidence-based approaches to workforce wellbeing.

NHS England. (2023). NHS England » NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES).

Noble, H., & Mitchell, G. (2016). What is grounded theory?. Evidence-based Nursing, 19(2), 34-35.

Riley, R. (2023). Postvention guidance supporting NHS staff after the death by suicide of a colleague [Slide show]. University of Surrey.

Samaritans. (n.d.). Latest suicide data.

Sullivan, S., & Germain, M. L. (2020). Psychosocial risks of healthcare professionals and occupational suicide. Industrial and Commercial Training, 52(1), 1-14.

The Alliance of Hope for Suicide Loss Survivors. (c2024). What is suicide Postvention? | Alliance of Hope for Suicide Loss Survivors. Alliance of Hope for Suicide Loss Survivors.

Photo credits

- Photo by Priscilla Du Preez 🇨🇦 on Unsplash

- Photo by Nicolas J Leclercq on Unsplash

- Photo by Jehyun Sung on Unsplash

- Photo by Luis Melendez on Unsplash

- Photo by Nappy on Unsplash

Dear Brittany and Sarah,

Thank you for reviewing the Spiers et al postvention paper. You may not be aware but we have produced the first evidence based postvention guidance for staff impacted by the suicide of a colleague which can be found here and may be helpful for NHS colleagues and managers to be aware of. We have disseminated widely through NHS Employers, RCPSych, and at national and international conferences and other fora. The guidance can be found here:

https://www.surrey.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2024-09/postvention-guidance.pdf

You might also be interested in Wellcome Trust project looking at understanding the elevated rates of suicide in female nurses. This is a 5-year project which includes five different studies.

Thank you.

Dr. Ruth Riley – Principal Investigator