Being a prison inmate increases your likelihood of early death (Pridemore, 2014). Available data suggests that death by suicide among prisoners is 5-6 times as common, compared to non-prisoners in England and Wales, with evidence of a much greater difference among women. Prison suicide rates in England and Wales appear to be increasing, but we have limited information on risk factors, changes over time, and the role of prison characteristics.

Mental illness, use of drugs, and repeated self-harm are risk factors for suicide in the general population, but evidence relating to prisoners is limited. Moreover, although prison overcrowding is considered an important policy problem, the role of prison overcrowding on suicide is inconsistent (Huey & McNulty, 2005). There is a reported association between suicide and characteristics of the neighbourhood in which one lives, but it’s unclear whether this association represents a causal effect (Chaix et al, 2006).

Being in prison dramatically increases the risk of dying by suicide, especially in women.

Methods

Fazel and colleagues looked at prison-based suicide from 2011 to 2014 across 24 wealthy countries; examining rates of suicide, rate ratios compared with the general population, change in prison suicide rates over time, and association with prison-level and wider ecological risk factors.

To gather data, investigators searched the internet for data on prison suicides from 24 countries based on defined search terms. Prison research departments were contacted for information, and information taken from the Council of Europe’s annual penal statistics publication. Different definitions of suicide between countries were noted, and included together and analysed separately, with few differences found based on definitions. Comparisons were made within each country with the general population rate of suicide in those aged 30-49.

A group of ecological variables (measured at the level of the country), were tested as predictors: the country-level incarceration rate, prison overcrowding, prisoner staffing ratios, prison turnover, prisoner costs per day, number of forensic inpatient beds as a proportion of the general population, whether prison management was publicly or privately-run, and the mean length of imprisonment. The same data was collected 2003-2010, in order assess changes in suicide rates over time. This paper is framed as an update to a previous report on prison suicide published in 2008.

Rates of suicide were compared with the general population using meta-regression. Countries with small numbers of suicides (<5), and with very high rates of incarceration (USA) were left out for some analyses. Data for some years, and broken down by gender, were unavailable for some countries. A number of further analyses assessed the role of temporal trends, gender, prison throughput and sentencing status, suicide definitions, length of imprisonment, and, in the USA, the type of correctional facility.

Results

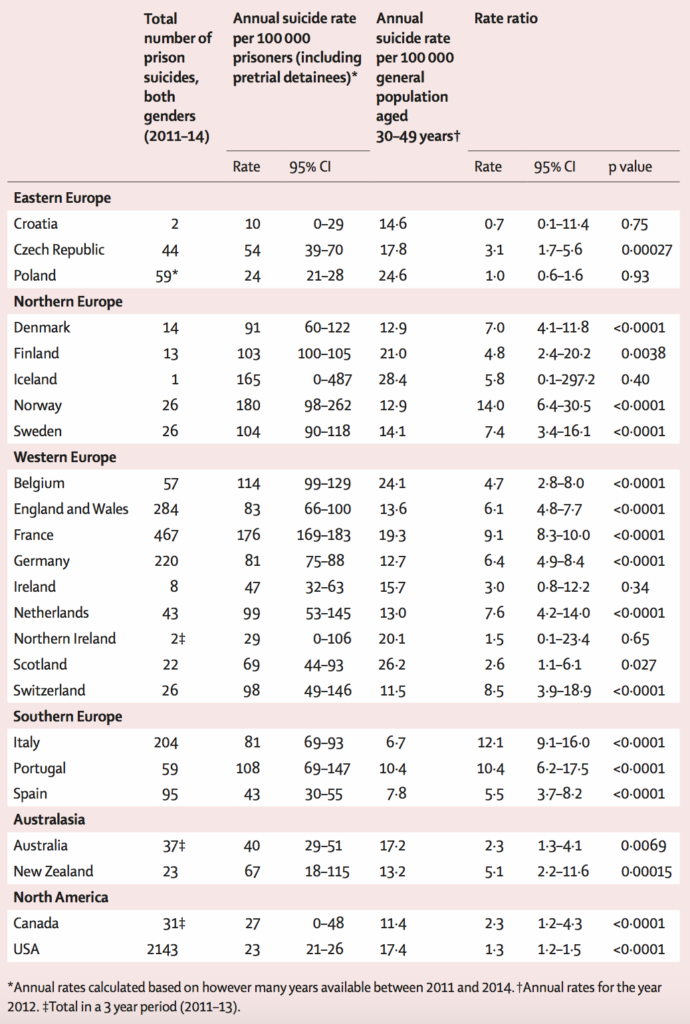

Table 2 in the paper shows prison suicide rates by country:

- The authors found that 3,906 suicides occurred in prisons in the countries included

- 93% of prison suicides were in men (gender information was available for about 3/4 of suicides)

- Rates of prison suicide varied greatly; with around 20 suicides per 100,000 prisoners per year in the USA compared with 180 suicides per 100,000 prisoners per year in Norway

- In comparison to the general population, prisoner suicide was not more common in Poland, but was 14 times more common in Norway

- Rate ratios were generally stronger in women than men

- Incarceration rates across countries were negatively associated with the rate of prison suicides, but this became less strong and possibly irrelevant once other variables (general population suicide, overcrowding, mean spend per prisoner) were included in the statistical model

- Turning to time trends, suicide in prisoners in Scotland reduced between 2003 and 2014, but no other statistically robust time trends were found

- In America, rates of suicide in prison were highest in local jails, then state prisons, then federal prisons

- Prison suicide was most common in Nordic countries, then Western countries, and then Australian and North American countries.

Many countries in northern and western Europe have prison suicide rates of more than 100 per 100,000 prisoners per year.

Implications

The authors suggest that Norway and France might have relatively high rates of prison suicides because they employ a broader definition of what constitutes a prison suicide, but they consider this unlikely, based on the analyses they were able to conduct.

No associations between prison suicide and prison characteristics were found, other than a relation with incarceration rates, which is suggested to require further investigation. The authors propose that this indicates that prison level factors (e.g. overcrowding and prison officer numbers) might not be so relevant, compared with the characteristics of individuals; particularly mental health and substance use.

Is it possible that overcrowding and staffing levels have little impact on prison suicide rates?

Summary

This was an ecological analysis of 24 countries’ data on prison suicide, in relation to a range of country-level characteristics on prisons, which found higher rates in some countries than others, higher relative rates in women than men, and a limited role of ecological factors on prisoner suicide rate.

The tables present useful summary information on prison suicide, and authors probably analyse this data as far as the data itself allows. It is not clear if the countries selected were chosen before they embarked on the analysis, or whether the missing countries simply reflect missing data. I wondered what the rationale was, before conducting the study, for focusing only on high-income countries. Although the implications as stated are that “individual-level factors or interactions between them and the prison environment might provide more explanation than solely focusing on prison-level factors for the large variations in prison suicide rates in different countries”. I am not sure that prison-level factors have been assessed here, given that data on prisons is grouped at the level of the country. Such a small number of countries analysed limits statistical power to assess the impact of ecological variables, so I would suggest this is inconclusive, although the point that individual factors are likely to be more important is plausible.

George Davey Smith suggests that a useful way of thinking about the significance of a piece of research is to compare it to a perfect study (Smith, 2007). For the topic of imprisonment and suicide, including potential causes, this could be a follow-up study of the general population of countries, gathering information on social demographics, health, time of any imprisonment, and cause of death. This would allow assessment of behavioural and substance-related factors before the prisoner was incarcerated, which might be responsible for any association between imprisonment and suicide, assessment of intermediate factors between imprisonment and suicide (such as being assaulted in prison, developing psychosis or other mental illness, or experiencing a serious physical health problem), and the characteristics of the prison (e.g. staffing ratios). Sadly, this fantasy study is very far from the real landscape of data availability on this topic, which is of crucial importance given the societal and other costs of suicide in incarceration. I hope that this new study will be useful in making the case for action to reduce the number of prison-based suicides, but also for better data including on individual health-related factors (Fazel et al, 2017).

Individual-level information about prisoner health is required to understand the substantial variations reported and changes over time.

Commentary

We are grateful to Dr Andrew Forrester for writing the following commentary on this new study:

“This is an important new study that examines 3,906 suicides in prison across 24 high-income countries over the three-year period until 2014. It challenges some of our existing assumptions about prison suicide because none of the prison-level factors studied were associated with suicide rates, but the data also leaves us with some unanswered questions regarding a number of prison ecological factors (e.g. use of meaningful activity, education and access to ligature points). It confirms the vital role of individual factors (including sentence length, history of self-harm, ethnicity and some clinical factors).

In practical terms, this study describes some important differences between countries that now merit further international discussion and thought. It also confirms that there is no unitary solution to prison suicide prevention, and it suggests that a renewed focus on identifying and managing individual factors should now be prioritised. This includes improving existing mechanisms for screening and case identification, and ensuring that an appropriate range of services are available across the spectrum of mental health issues. Mental disorders are over-represented across the board amongst prisoners, but many services have until now tended to focus narrowly on severe mental illness to the relative exclusion of common mental disorders. Mixed pathologies, underlain by substance misuse and/or personality disorder, are the rule rather than the exception in prison mental health clinics, and services need to be sufficiently resourced to manage this level of complexity.

In both policy and practice terms, this work confirms the need for a joint approach to suicide prevention between health and justice agencies. Improved information sharing through agreed protocols, and enhanced mental health training for prison officers, would both be useful to consider at this stage.

In research terms, there is much to be done in this area in which experimental research is both sparse and difficult to achieve. Screening at prison reception, then subsequent triage within the first three days, would be useful research targets at this stage, as would identifying appropriate clinical interventions for application in a prison setting.”

Screening at prison reception, then subsequent triage within the first three days, would be useful research targets at this stage, as would identifying appropriate clinical interventions for application in a prison setting.

Links

Primary paper

Fazel S, Ramesh T, Hawton K. (2017) Suicide in prisons: an international study of prevalence and contributory factors. Lancet Psychiatry 2017

Other references

Pridemore WA. (2014) The Mortality Penalty of Incarceration Evidence from a Population-based Case-control Study of Working-age Males. Journal of health and social behavior 2014: 0022146514533119. [PubMed abstract]

Huey MP, McNulty TL. (2005) Institutional conditions and prison suicide: Conditional effects of deprivation and overcrowding. The Prison Journal 2005; 85: 490-514. [Abstract]

Chaix B, Rosvall M, Lynch J, Merlo J. (2006) Disentangling contextual effects on cause-specific mortality in a longitudinal 23-year follow-up study: impact of population density or socioeconomic environment? International journal of epidemiology 2006; 35: 633-43. [PubMed abstract]

Smith GD. (2007) Lifecourse epidemiology of disease: a tractable problem? International journal of epidemiology 2007; 36: 479-80.

Interesting study, looking at the prison population within the age group of 30-49 whereas ONS (General Population) uses 30-44 age group which in 2014 showed a death rate of 21.3% per 100,000 population. In agreement with the commentary which support NICE Guidelines 57 & 66 and PHG95 due September 2018.