Suicide is a major cause of premature death worldwide with an estimated 800,000 people dying by suicide each year. A surprising fact to some people is that 76% of all these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (WHO, 2014). Despite this high burden, we know relatively little about suicide in LMIC, partly because the health focus has primarily been on communicable diseases.

It is imperative that we gain a better understanding of suicide in LMIC and ensure that the scant resources in these settings are targeted at the right places to prevent suicide. Our growing understanding is that suicidal behaviour in LMICs may not have the same risk factors for suicide as high income countries (HICs); For example, the number of people who attempt and die by suicide has been found to be much lower compared to HICs (Roberts, 2019).

Good quality large scale community studies are desperately needed in these settings which assess suicidal behaviour and its correlates. One such study has recently emerged from India, where 18% of the global population live, but where nearly 30% of suicide deaths occur. Amudhan and colleagues (2020) have looked at the prevalence and related sociodemographic factors of ‘suicidality’ in a large cross-sectional survey of nearly 35,000 people in India. The authors define suicidality to include suicidal ideation, intent, plans, and attempts.

76% of suicide deaths occur in low and middle income countries, but we know relatively little about how to prevent suicide in these settings. [Image by Ery Burns].

Methods

The aim of the study was to investigate the prevalence and sociodemographic differences of suicidality from data collected as part of the National Mental Health Survey of 12 states in India. Data were collected by a household survey of adults >=18 years) by trained data collectors in the local languages.

Suicidality was assessed using the suicidality module of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). This module included questions that were related to both suicidal and non-suicidal phenomena. For this study the non-suicidal questions were excluded. Only scores from questions relating to suicidal ideation, impulses, planning, intent, preparation, and attempts were used to calculate a suicidality score. This was then categorised into low, medium, high or overall suicidality.

Statistically the authors used normalised sampling weights to examine sociodemographic differences in suicidality. They also calculated age-standardised suicidality prevalence rates for men and women in the 12 surveyed states, as well as sex ratios, ratio of suicidality to deaths and suicide attempts to suicide deaths.

High rates of suicidality are reported in India with differences in sociodemographic differentials (e.g. women and people in lower socioeconomic positions having higher rates).

Results

- 34,748 (88% of those approached) completed the survey, with mostly young (54%), female (52%), married (75%) individuals, living in rural (69%) areas responding to the survey

- One in twenty people reported some level of suicidality in the past month

- Overall prevalence of suicidality was highest in:

- women,

- individuals with lower levels of education and income

- widowed/separated/divorced individuals

- those living in urban metropolitan areas

- The authors also reported an association between depressive and alcohol use disorders and suicidality.

Overall suicidality appears to be highest in 40-49 year old women, and men over 60 years. Although this pattern wasn’t as apparent when looking at those with moderate to high suicidality.

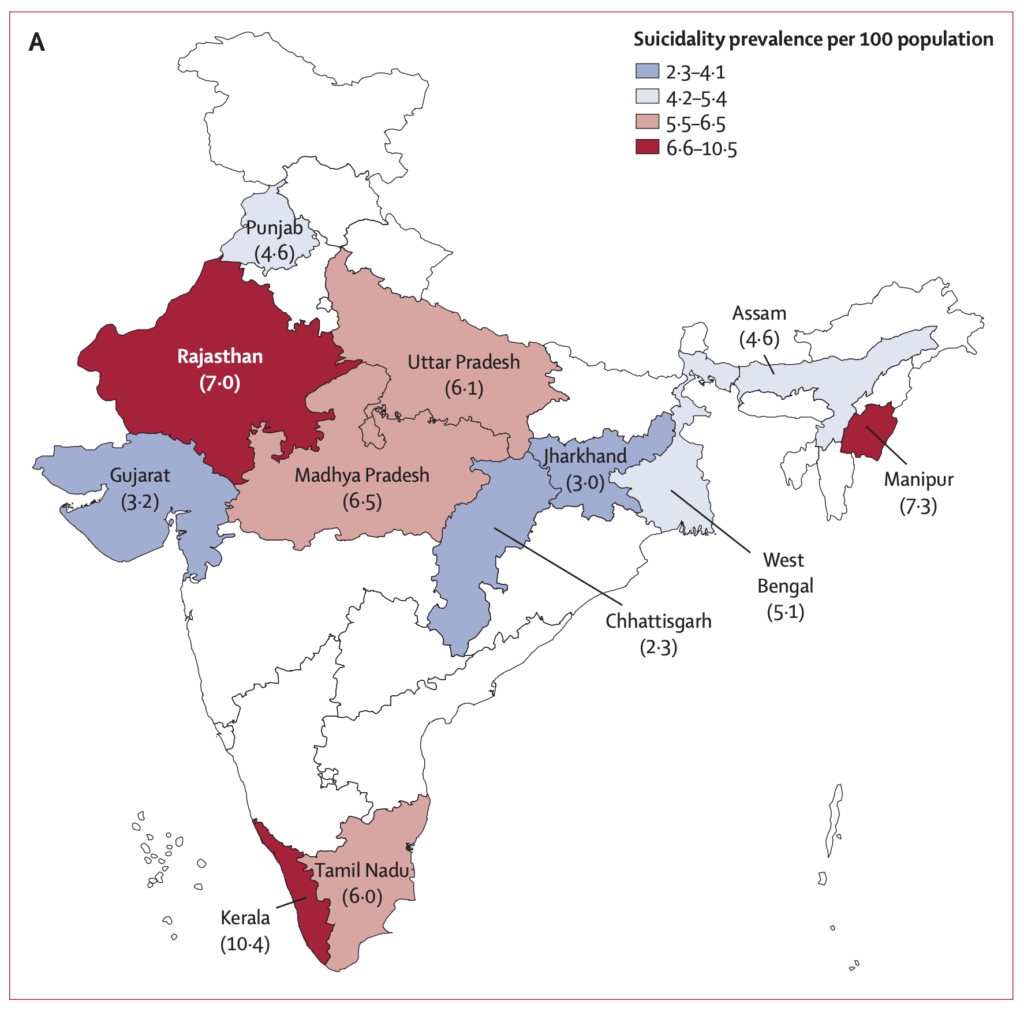

Figure 3: Weighted and age-standardised prevalence of suicidality and suicide deaths by state in India, 2015: suicidality prevalence per 100 population. [Taken from Amudhan et al, 2019].

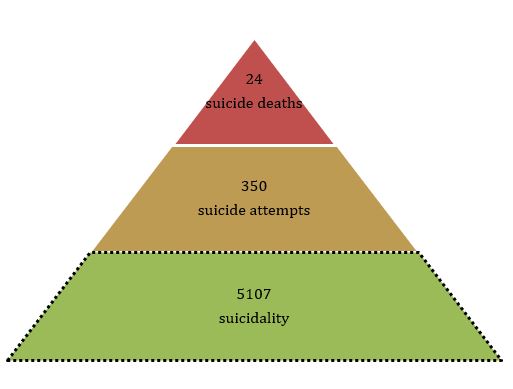

The prevalence of suicidality was higher in Kerala, Manipur, and Rajasthan. There was large variation between states in terms of rates of suicidality and sex ratios. Authors also report that the pattern of suicidality distribution differs to that of suicide deaths between states, with rate ratios ranging from 1:85 to 1:396. They suggest that the differing distribution indicates heterogeneity in the factors that lead from suicidality to suicide deaths. Overall, however, the rate ratio of suicide deaths to suicide attempts and suicidality was 1:15:212.

Overall, the rate ratio of suicide deaths to suicide attempts and suicidality was 1:15:212. The factors that affect and lead from suicidality to death by suicide are, however, not clear.

Conclusions

5% of adults in India reported at least one suicidality experience, with 1% being scored by authors as experiencing high suicidality. For every suicide death only 15 people had attempted suicide, but over 200 had reported feeling some form of suicidality.

This is an impressive population-based study of suicidality in India, which estimates that more than 44 million adults in India could experience suicidality. The authors state that:

addressing suicidality in India is crucial to make global difference in suicide prevention.

The paper estimates that more than 44 million adults in India could experience ‘suicidality’.

Strengths and limitations

Despite this study only including 12 states in India, the sample is likely to be representative of the Indian population given the similarity in sociodemographic variables to the 2011 Indian census. The large sample size and the wealth of data variables collected makes this a valuable data source and study. The fact that the study collected data on self-reported suicidal behaviour (particularly suicide attempts) is a strength as it doesn’t depend on individuals presenting to a health care facility after an attempt. In countries where suicide is stigmatised and criminalised, community self-reports may be more reliable in estimating prevalence.

Given the data available to the researchers, it was disappointing that the authors presented the findings of the suicide and self-harm measures they had as a composite score. The suicidality measure used throughout the study is, in my opinion, its biggest limitation. The suicidality measure incorporates a wide spectrum ranging from passive suicidal ideation to active attempts. This is problematic. The authors argue that the “MINI categorisation [is] more pragmatic and sensitive than restricting to suicide attempts alone for any public health actions and clinical decisions towards suicide prevention”. I’d argue against this. In settings where suicidal behaviour is prevalent and is sometimes used as a communicative tool, suicidal thinking (particularly passive ideation) is highly likely. This thinking, however, does not always relate to active suicidal behaviour.

In countries where suicide is stigmatised and criminalised, community self-reports may be more reliable in estimating prevalence.

Implications for practice

Amudhan et al. argue that public health approaches for suicidality and suicide should not be compartmentalised, and they call for an applaudable approach which combines universal, selective and indicated interventions through multi-sectoral public health approaches.

From personal experience I know that I’ve had moments of feeling suicidal, but they have been momentary and I would never act on these thoughts. Should I be the target of an intervention? This paper could have been considerably strengthened by including a sub-analysis looking at the different components of the score i.e. suicidal ideation, plans, intent and attempts. As a composite score it assumes that suicidal ideation, plans, intent and attempts lie on a continuum. The current evidence suggests that suicidal ideation (the assumed start of this continuum) poorly predicts suicide in both psychiatric (positive predictive value: 3.9%) and non-psychiatric (0.3%) samples (McHugh C. et al 2019). The subgroup analysis would have gone some way towards providing more convincing evidence that suicidality should be a target for suicide prevention. If it truly was a good target for intervention, we would see similar associations between each item of the score as you would do overall.

The composite score of suicidality assumes that a person who attempts or dies by suicide has previously experienced suicidal ideation, plans or intent. This may not be the case, which has implications for clinical practice.

Statement of interests

Dee Knipe is an epidemiologist with a special interest in suicide in low and middle-income countries.

Links

Primary paper

Amudhan S, Gururaj G, Varghese M. et al (2020) A population-based analysis of suicidality and its correlates: findings from the National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015–16. Lancet Psychiatry 7(1) 41-51.

Other references

McHugh, C., Corderoy, A., Ryan, C., et al (2019). Association between suicidal ideation and suicide: meta-analyses of odds ratios, sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value. BJPsych open, 5(2), e18. doi:10.1192/bjo.2018.88.

Roberts, R (2019). Suicide and mental illness in low- and middle-income countries. The Mental Elf.

WHO (2014). Preventing suicide—a global imperative. Geneva.

Photo credits

- Photo by Ery Burns

- Photo by San Fermin Pamplona – Navarra on Unsplash

- Photo by D A V I D S O N L U N A on Unsplash